Jurassic Park Below

In dark depths rarely visited by scuba divers, subs explore hectares of sponge many storeys high that form British Columbia’s ancient Sea of Glass

By Sabine Jessen and Alexandra Barron

The Aquarius submersible plummets through the depths, the light fades and darkness surrounds the small white vessel. Through the thick acrylic viewport, the spotlights of the sub light up the marine snow, plankton and detritus falling from the surface. As the submersible sinks faster it appears to snow upwards! The submersible keeps falling: 50 feet, 100 feet, 150 feet…. The tiny submersible and its three passengers are now deeper than most SCUBA divers will ever go. 200 feet, 250 feet… Then bingo! Out of the darkness bizarre, alien forms slowly appear, sprouting from the seabed. “We have glass sponges at this location,” says Jeff Heaton, our pilot, over the communications system, to the jubilation and relief of the crew at the surface.

The sponges glow eerily in the beam of Aquarius’ spotlight: white, orange and yellow, against the inky-blackness. Among them dart schools of brightly coloured rockfish, shrimp scuttle for cover and decorator crabs wave their claws in warning, perhaps. Against the surrounding darkness it is an explosion of colour and activity. In the words of glass sponge expert Dr. Sally Leys, “Kapoof. An oasis of life.”

It’s an unseasonably beautiful October day, and the B.C. chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS) marine conservation team, along with Nuytco Research Ltd.’s submersible surface support crew, journalists and scientists are enjoying the warm sunshine and flat-calm seas from a barge just off the West Vancouver shore. When the sea mist clears there are stunning views of Vancouver’s glass skyscrapers glistening in the sunshine, but the crew is here for glass structures of a very different kind. The crew is here for the glass sponge reefs.

Glass sponges use silica (glass) that is naturally dissolved in seawater to construct their skeletons, which have the consistency of a meringue or a prawn chip. Reef building occurs when living glass sponges grow on top of dead glass sponge skeletons. High concentrations of silica provided by B.C.’s coastal mountains are probably one reason why glass sponges thrive in this area. Glass sponges can be found in several locations around the world, particularly Antarctica, but they don’t build reefs there. In fact, B.C.’s reefs are the only known living glass sponge reefs in the world, and scientists have only been aware of them for the past 25 years.

Exploring the deep

Exploring the deep

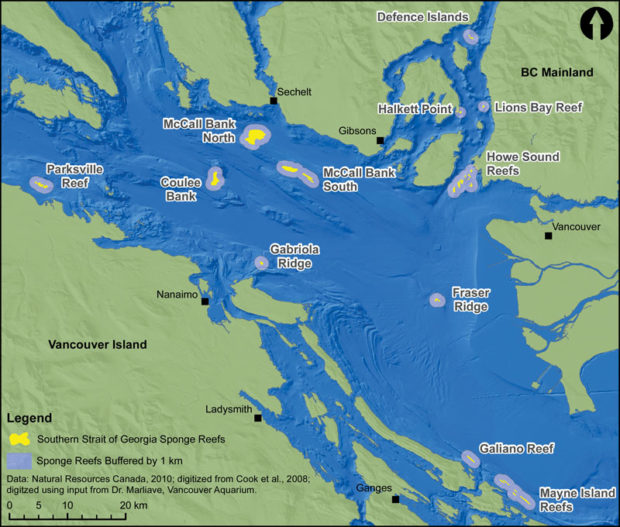

In 1986, a team of scientists from Canada made a remarkable discovery. While mapping the seafloor of Hecate Strait on the north coast of British Columbia they found strange mounds at water depths of 500 to more than 800 feet (150-250m). On closer inspection with an ROV, the mounds were found to be immense glass sponge reefs reaching eight storeys high – 80 plus feet (25m) – covering 270 square miles (700 square km) that had been growing on the seafloor for 9,000 years. In 2001, a survey of British Columbia’s south coast found several more reefs dotted along the Sunshine Coast, in Howe Sound, the Gulf Islands and at the mouth of the Fraser River. These reefs are generally smaller than their northern counterparts, but still reach a respectable 46 feet (14m) in height, and up to 20 sq. miles (50 sq. km) in area.

Jurassic Park. Submerged

Prior to their discovery in British Columbia, glass sponge reefs were believed to have gone extinct 40 million years ago, in the Jurassic Period. The only known records of their existence were massive fossilized sponge reefs in Europe. Dr. Manfred Krautter, a palaeobiologist from the University of Stuttgart in Germany who has devoted his academic career to the fossilized reefs, remembers almost falling out of his chair when he read the paper describing the living sponge reefs. He likens the discovery to finding a herd of living dinosaurs on land!

Most of the reefs are more than 330 feet (100m) deep, beyond the limits of most recreational divers, which explains why they hadn’t been seen before then and why the reefs are not popular dive sites. In an attempt to reach one reef, a team of experienced divers using trimix managed a total of 15 minutes on the reef before having to start their slow and arduous ascent. There are pockets of glass sponges living in shallower waters throughout B.C., particularly in Howe Sound. They are a favourite with divers because of the abundance and diversity of life, especially charismatic rockfish, that surrounds them. However, these pockets are not reef-building glass sponges, they are loosely referred to as ‘sponge gardens’. The relationship – if any – between the gardens and the reefs is not known.

Dr. Sally Leys and her research team at the University of Alberta use ROVs to survey the reefs and study various aspects of sponge biology, including how they feed and what they feed on, how they grow – and what kills them! The Leys Laboratory has calculated that a single reef can filter an Olympic sized swimming pool of water in a minute and that they remove about 95 percent of bacteria from seawater. This makes glass sponge reefs incredibly important natural water filters, especially in semi-enclosed and highly developed water bodies like the Strait of Georgia. Dr. Leys and her team are also looking at larval settlement to see when and how sponges spawn and where the juveniles settle, but so far glass sponge reproduction remains a mystery.

Oasis of Life

At 330 feet (100m) deep the seabed is a dark, desolate place where life is sparse; but where there are glass sponge reefs, life thrives. One of the first things scientists noticed about the glass sponge reefs was the large number of brightly coloured juvenile rockfish found around the reefs, as well as crabs, prawns and other marine animals. Glass sponge reefs play a very important ecological role as nursery habitats. The complex structures and large tubes (called ‘oscula’) provide plenty of hiding places, making them ideal nursery grounds for vulnerable juveniles and small critters. They are particularly important as rockfish nurseries because rockfish populations have been declining in B.C. largely due to overfishing and accidental bycatch. Rockfish cannot adjust to pressure changes at the surface because of their closed swim bladder and so cannot be released alive when accidentally caught, although rockfish ‘decompression technology’ (some of which is very similar to that for human divers) does exist.

Broken Glass

Not all of the early discoveries were good news. Video surveys of the Hecate Strait reefs performed not long after their discovery showed vast areas where bottom trawling fishing gear had ploughed the magnificent reefs, crushing the glass sponges, reducing them to rubble and dust. The Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society has been advocating for the protection of the glass sponge reefs since 2001. In 2002, the Canadian government implemented fisheries closures around the Hecate Strait reefs to stop destructive bottom trawling in the area and protect the glass sponge reefs from physical damage.

But the reefs need protection from more than just bottom trawling. Research by Dr. Leys has demonstrated that too much sediment in the water can choke glass sponges; causing them to stop feeding, sometimes for long periods, or until they die. The worry is that fishing and bottom contact activities near to the reefs can create sediment plumes that temporarily starve the reefs so that they lack the energy needed to grow and reproduce. If it continues, the sponges will die.

One strategy to protect the reefs is the establishment of marine protected areas (called MPAs). By managing all activities that take place over a large area, conservationists and resource managers can ensure that the fragile glass sponge reefs are protected from all known threats. CPAWS is currently working with the Canadian government, other conservation organizations and the fishing community to establish an MPA around the Hecate Strait reefs, with boundaries and management strategies that will prevent the reefs from both physical damage and sedimentation, while allowing non-harmful fishing practices to take place. The Hecate Strait glass sponge reef MPA will hopefully be finalized in 2014.

The reefs in the Strait of Georgia have no legal protection as yet, although fishing closures are anticipated in early 2014. The purpose of the CPAWS submersible expedition was to check the condition of one of the southern reefs and raise awareness about these important ecosystems in order to hasten the establishment of protective measures.

Back at the dive site, the Aquarius submersible is exploring the Howe Sound Reef. The last detailed survey of Howe Sound Reef was performed in 2009, and noted patchy coverage by glass sponges with areas of damaged reef. On a reconnaissance trip to the site in August, the CPAWS team had witnessed a trawler actively fishing over the reef and captured drop-cam footage of stranded prawn traps and ghost-fishing gear, stuck between glass sponges on the seabed. As the submersible began its descent, the team really wasn’t sure what they would find, but hoped that the sponges had survived these invasions. The passengers and crew were able to breathe a sigh of relief. They found plenty of glass sponges and not much damage in the small section of reef they are able to survey. However, unless conservation measures are implemented quickly, all could be lost in the blink of an eye.

Sabine Jessen is the National Director of CPAWS’ Oceans Program and Alexandra Barron is Marine Conservation Coordinator at CPAWS-BC Chapter. CPAWS is a non-profit, grassroots-based conservation organization with 13 chapters across Canada. CPAWS remains the only national non-profit organization devoted exclusively to protecting Canada’s wilderness heritage and establishing marine protected areas throughout Canada’s oceans.

Leave a Comment