What it Takes to Shoot a Feature Film

By Jill Heinerth

Gliding along with the precise synchronicity of a flight demonstration team, scuba divers piloting radical-looking scooters maneuver into the frame. As viewers we are transformed, drawn into the dimly lit cave of indescribable beauty. If the Director of Photography has done his job, we are engrossed in the wonder of the story. Some people have said that feature films are like sausage: they might be tasty to consume, but you don’t necessarily want to see how they are made. However, I am going to assume that the readers of this column are eager to know the nitty gritty details of what it takes to make a feature movie and tell you about one of my experiences.

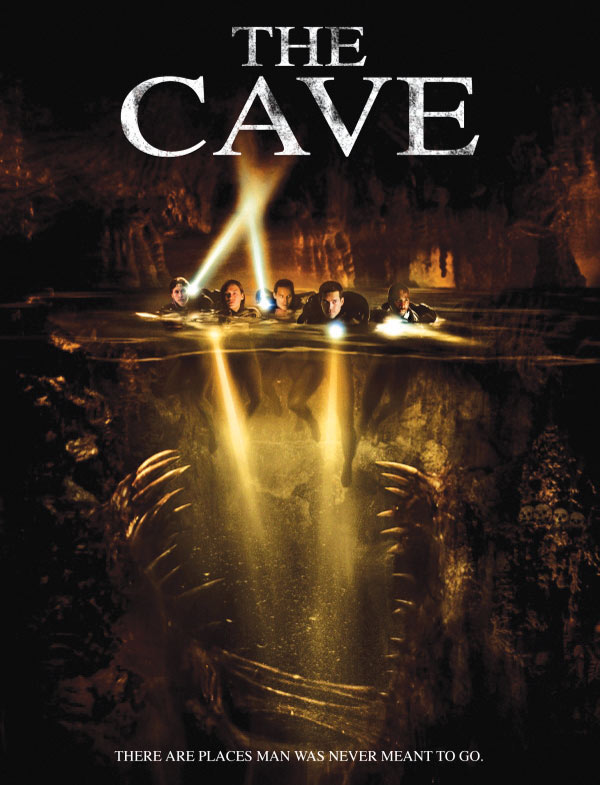

A few years ago, I got a call from a Hollywood studio asking me to lead the Underwater Unit in making the movie ‘The Cave’. Little did I know at the time, my daily role would include producing, stunt diving, directing, script supervision, wardrobe consultation and safety. I even had to help build the rebreathers used in the film, and train the actors to dive them. My job would defy description and cross over to every department on the set. With over 1500 people involved in making ‘The Cave’, that also meant a lot of new friends.

I spent almost eight months in Los Angeles and Romania in the prep and set shooting, but it was the location work in Mexico that was the most memorable. We had completed all the stunts, tricks and anything that might damage a cave environment within the confines of constructed caves on set, and were ready to move on to beauty shots in natural caves. It was a monumental task of organization, bringing 40 people together in the jungle for one month to get the job done.

The underwater footage in Mexico was shot using a Sony F900-3 camera in an Amphibico housing. Unit Director Garry Phillips could sit inside an air conditioned tent with an HD engineer and audio specialist, but Wes Skiles and I, along with 16 other cave divers, were hard at work bringing the scenes to life underwater. This meant that an incredibly long cable was needed to connect Phillips to Skiles, deep inside a cenote within Sistema Dos Ojos. Every inch of that cable had to be managed by a team of divers to ensure that we did no damage to the pristine cave.

I recall one particular dive with great clarity. After an entire morning of preparation and rehearsal, Brian Kakuk and I were dressed appropriately in the wardrobe of the actors for whom we were doubling. I was playing Fast and Furious star Cole Hauser, grandson of media magnate Jack Warner (Warner Brothers), and Brian was on deck as Morris Chestnut, of Anaconda fame. My job was to drive a scooter while pulling a large sled filled with about 600 pounds of weighted Pelican cases and packs while Brian hung on and steered from behind. A squadron of divers delicately threaded their way into a gallery of stunning cave formations. Tom Morris and Woody Jasper slipped behind some large speleothems carrying huge lights, deftly maneuvering them to avoid disturbing the silt. Other underwater grips quickly followed their lead. Mark Long eased the slate in front of the camera and hit the clapper while Wes pulled his final white balance. Safety divers held with Brian and I at the launch point behind the camera.

“Speed…and ACTION!” Wes hollered through his Ocean Systems comms. My ear bud crackled with the indication to launch and I hit the throttle on full.

We glided over Wes as close as we could to create an illusion similar to the Millennium Falcon soaring through space. I heard him voice “Yeahhhh.” Panning our lights around the cave in a well orchestrated dance, Wes commanded, “Uncover one. Uncover two. Uncover three. Cover one. Cover two. Uncover four.” One at a time, the underwater grips sprang into action. With each order a large garbage can lid was eased off of a lighting fixture, revealing the light briefly before slowly hiding it as we drove beyond the mark. Each diver was either hidden out of frame or concealed by their rebreather, prohibited from creating any bubbles that would destroy the illusion.

“And… CUT!” Wes yelled. I heard Garry’s voice from topside declare, “Wow!” Then my heart sank when I realized my scooter was stuck and would not turn off. We had been struggling with sticky triggers throughout the shoot, but here I was in this remarkable museum of crystalline formations, unable to stop.

Frantically, I yelled to Brian, “Let go! I can’t stop this thing,” while darting between rocks and running away from our colleagues. I didn’t want to horse collar him on an overhang and was hoping he might be able to jettison the 10-foot sled from my crotch strap. But my brother in cave diving had other ideas, “I’m staying with you,” he screamed back. And so we went on a wild ride, dodging stalagmites and weaving through silty corridors, determined not to make any damage. I pounded on the magnetic read switch and then on the housing of the scooter. Having experienced the sticky switch before, I now carried a two-pound chunk of lead in my glove for just such an emergency. Swinging my arm like a circus strongman with a sledgehammer, it didn’t make a bit of difference. Brian hung on yelling, “Woo hoo!” and laughing at our predicament, while safety divers hopelessly gave up the chase. Wes, wondering where the talent had disappeared to, rallied the team out of the cave.

Finally many spine-chilling minutes down the road, Brian and I lapped back to the entrance and finished our joy ride. I found a spot by the deck to bury the nose of the scooter into the silt and detached myself from the bucking underwater bronco. A topside team manhandled the runaway scooter from the water, opened the housing, and detached the battery. Injury averted. Wildly spinning prop blades neutralized. This experience is one of the many reasons I think that cave diving for movies is even more dangerous than the real thing!

In the end, ‘The Cave’ was panned by the critics. However, there were huge kudos for the impressive underwater scenes. Unfortunately, the stunning beauty of ‘The Cave’ could not overcome the cliches and weak character building of the plot.

If you are looking to pass an evening enjoying extraordinary underwater videography, and can ignore a bit of sensational Hollywood drama, then check out ‘The Cave’.

I’m the diver girl, playing all the diver guys…

Leave a Comment