Interview: Brett Seymour

Deputy Chief / Audiovisual Production Specialist with the National Park Service Submerged Resources Center

How long have you been diving?

I completed my NAUI Open Water 1 in 1993.

What made you want to become a diver?

Like so many before me, I grew up watching Cousteau – (the old version, where Falco and Dumas did most of the diving). The ship, the equipment, the images always fascinated me. As kid I spent hours trying to stay underwater in a frigid New Hampshire lake with all manner of contraptions—long hoses, overturned 5-gallon buckets weighted with concrete blocks, etc. I also spent many summers on my uncle’s lobster boat off the coast of Maine pulling traps, fascinated with what the underwater world held. As a mid-schooler I had a subscription to Skin Diver Magazine and was in awe of the underwater world (and the horrible neon lycra/spandex dive suits of the 80s). I always wanted to explore and document what so few had ever seen. The thought of exploring the underwater world always held a part of my upbringing. I never just wanted to dive recreationally as a pastime, but as a career.

How did diving change your life?

I didn’t learn to dive until I was at university studying photography and film. After graduating and learning about the National Park Service (NPS) Submerged Resources Center, I was all in to pursue a career in underwater imaging with the NPS. Despite ambition, passion, and a strong work ethic it still took over 7 years of volunteering and tiny contracts, before I competed for a federal permanent position with the NPS Submerged Resources Center.

What does diving mean to you?

To me, diving means access to hidden and tremendously important part of our world. It might be history or the natural world. To be honest, I don’t consider myself a diver. I’m a photographer who uses diving for access to image what I’m passionate about. Despite decades of training in diving modes, gasses and equipment (with all the C-Cards) that go along with each progression, it’s always been about the right training and equipment for the right assignment.

Why is Submerged Resources Center such an important part of NPS?

Why is Submerged Resources Center such an important part of NPS?

The NPS is the US’s lead conservation federal agency. I still find the mission to be inspirational: “…to preserve unimpaired…for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations”. How can we “preserve unimpaired” those areas we don’t understand or recognize—the underwater world? The NPS Submerged Resources Center was established for just that mission. As a national program with a massive scope, we assist parks and partners with the discovery, documentation, and management of anything underwater. Just as the NPS is responsible for back country trails, historic structures, and mountain parks, we have the same responsibility for underwater sites. The SRC’s role is to help the agency with that balance of public access and protection on underwater areas.

Why is NPS-SRC important to divers?

Our office doesn’t just work inside the NPS. We often partner with universities, other federal agencies, governments, or media partners. We also have a long history of contributing to the greater diving community. A classic example of this would be Bikini atoll, considered to the shipwreck mecca for many divers. It was our office in 1990s along with Department of Energy and the Navy who first explored the ships of the nuclear graveyard. The maps are still in circulation of the Saratoga and other ships were generated from NPS archeologist some 30 years ago. In addition to the mapping, the SRC was instrumental in establishing a dive community of site stewards in the Bikinian people to monitor and control diving access.

On a more recent timeline we regularly work with promising new talent in diving marine science by funding an internship with Our World Underwater Scholarship Society; support the proven therapeutic benefits of diving through ongoing Wounded Veterans in Parks projects; and our at-risk youth underwater imaging partnership with New Light Under the Surface. We also seek to contribute our knowledge or expertise of closed-circuit diving or innovative 3D photogrammetry imaging techniques in the greater underwater community through technical assistance or presenting at diving conferences.

We think you have the best job in the world!

I would imaging most would assume “this best job in the world” thing would be because I’m a salaried underwater photographer who doesn’t have to pay for equipment, travel, or training. I can’t underestimate how amazing these aspects of my job are; however, I believe I would be doing what I do even if this weren’t the case—maybe just with older gear! I believe the true reason of why it’s the best job is purpose. The images I generate have purpose. They support the understanding, management, education, exploration, or just simple interest of a dynamic range of potentially fleeting ‘resources’ underwater. Illuminating declining coral reefs, re-imagining historically significant shipwrecks, profiling wounded veterans who find purpose, mentoring at-risk youth who find healing in underwater photography, and the list goes on. I have great respect for talented underwater photographers who profile destinations or run photographic expeditions, but that’s just not for me. I have experienced the difference between imaging a WWII aircraft and partnering with the Department of Defense to documenting an excavation of that aircrafts crew to bring closure to family. I can tell you there is no comparison on a personal or professional level. My years as a documentary project photographer—where the archeologist or scientist would not pause underwater to set up an image—has crafted a skill of capturing a story in a single frame as it happens. The benefit of having film early in my career also helped greatly. When you are 190 feet (58m)deep on open circuit mixed gas and you only have 36 exposures to capture a site or project, you refine technique and abilities very quickly—or you don’t…and you won’t last long as a professional underwater shooter.

Lastly, and perhaps most rewarding personally, is the lack of copyright worries, stock images sales, or nondisclosures. Since I work for the federal government, shooting government equipment, the images I generate are largely in the public domain—which means accessible to the public with no copyright or cost. I can be incredibly generous with the media I create. Project participants, social media, magazine articles all benefit from images that have purpose or highlight a worthy expedition with no price tag. Occasionally a project demands the embargo of a collection of images or governmental release, but for the most part I am free to be generous without the need to generate income for use. The concept of sharing the underwater world with a wide audience has always been an underlying driver personally, even when I first started over 25 years ago.

Why is documenting important?

I’ve always believed we—as a society—only respond, engage, and fight for what we see—either first person or through imagery. The BP oil spill wasn’t real until photographers starting imaging birds drowning in oil. Today’s limited ocean resources’ only hope of salvation rests with photographers. Scientist may have the responsibility to conduct research, but I believe photographers own the need to communicate these findings. My work with the NPS has a similar mission. In addition to awareness to these threatened “resources” there is value in showcasing the recreational opportunities and diversity within the NPS—the Parks are held in public trust for everyone.

Pearl Harbor may be the most well known work the NPS-SRC does, what does this work mean to you personally?

I have been so fortunate to do more dives on USS Arizona than any other location in my 25 years with the National Park Service. This site has directly informed so much of my underwater photography. On the technical side, despite the Hawaii location, visibility is typically poor, only 5-10ft (1-3m). Documenting a 608ft (185m) WWII battleship in 5-10ft (1-3m) increments has been a career-long pursuit. From the human element, aside from the tremendous loss of life (1177) aboard the ship or the nearly 1,000 men still entombed, it’s the survivors that have taught me the most about WWII and its relevance in an ever-distancing society. I just lost a friend of many years, Donald Stratton, who was my first connection to a ‘living Arizona’ many years ago. Currently, there

are only 3 USS Arizona survivors alive. Don was a remarkable man. Voices like his are almost silent. There are incredible stories anchored in Pearl Harbor, the USS Arizona is the physical touchtone to that past.

How important are your professional relationships outside of the NPS?

My first love is and will always be the NPS. Aside from whatever talent I may have, they have provided everything else—opportunity, training, equipment, access—which has led to an amazing career. That being said, I believe in certain causes, partners, or projects enough to donate my photographic abilities to specific expeditions. I choose any external, non-NPS project on the bases of what I can contribute from a storytelling aspect, the uniqueness or challenges of the project, but most importantly if I really like the people. When you’ve spent 5-7 months a year for more than 20 years traveling, you really want to enjoy those expeditions, especially if they are taking you away from your family. But each external opportunity brings more capacity back to the NPS for documenting and sharing the underwater world.

What does the NPS-SRC’s future hold?

We are pioneering some incredible work in the area of photogrammetry and making our National Parks relevant and desirable. Structure from motion is currently in a place where ‘everybody’s doing it’, but along with our partners at Marine Imaging Technology and the UC San Diego’s Cultural Heritage Engineering Initiative (CHEI) we’re forging new ground in multi-camera acquisition and advance visualization of the underwater world.

Who is your go-to dive buddy?

I should probably say the incredibly talented divers we have at the NPS SRC, but if I’m being honest, it’s Evan Kovacs.

Evan Kovacs, owner of Marine Imaging Technologies, and I have done some amazing expeditions both inside the NPS and around the world. As a talented underwater cinematographer (in addition to being a mad genius engineer at all things underwater) we have worked some incredible sites from the South Pacific, to Greece and Croatia, with so many Parks in between. As a still guy jockeying for the best angle underwater, working with Evan, who is largely a motion guy and wants the same thing, we have developed a terrific in-water partnership to cover an underwater expedition—both creating the best imagery possible.

What is your favourite dive site?

In a strange way, I am most comfortable, and feel the greatest connection to the USS Arizona in Pearl Harbor. It may be difficult to imagine a site that you have dived approaching 500 times can still be a ‘favourite’, but the ship is constantly revealing a bit more of itself with each dive. I have such a deep personal respect and reverence for the USS Arizona that diving the site is still incredibly special.

Where would you like to dive but haven’t?

Antarctica—but I’m working on it.

Proudest diving achievement?

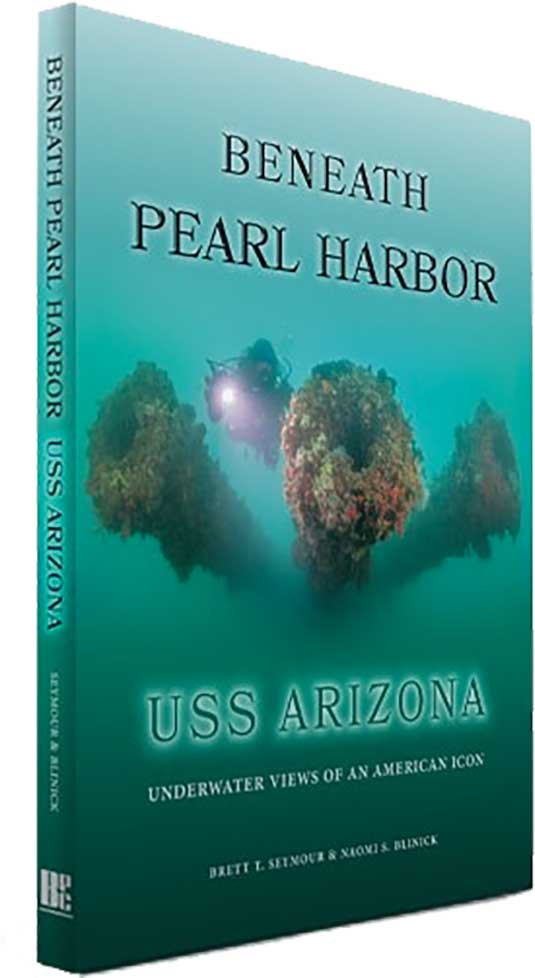

Beneath Pearl Harbor. For years I had a desire for a wider audience to experience the USS Arizona as few have ever seen it and hear the stories of those have been instrumental in the preservation and interpretation of the American icon.

What’s the craziest thing you’ve photographed underwater?

The Exosuit. It may sound a bit anticlimactic, but hovering from an archaic Hellenistic Navy vessel in the azure waters off Antikythera, Greece there was something crazy about a man in a machine—a single man in a single atmosphere diving suit—that was really remarkable. It reminded me of where ocean exploration had come from… and where sadly we have fallen short.

Favourite dive snack?

You mean the only dive snack? A Chocolate Brownie Cliff Bar. No other flavour.

Favourite diving movie?

Atlantis. A French film released in 1992 directed by Luc Besson, with underwater cinematographer Christian Petron (that grossed a whopping $138K in the US). Despite the less-than-amazing name, this incredibly beautiful film inspired me pursue a full-time career in underwater production. I was in film school at Temple University and attended a random Tuesday afternoon screening on a cloudy day. I was so moved by the film, which is just a visual experience of the underwater realm, that I begged the projectionist for the movie poster that hung in the marquee. That Atlantis one-sheet poster still hangs above my desk to this day.

Favourite piece of equipment?

X-CCR with a Shearwater NERD. I’ve never had a more reliable piece of diving equipment with the ease of critical data delivery for a photographer.

What’s next?

As much as I can fit in any given year. Bringing more of the underwater world of the National Parks to light, more Wounded Veterans In Parks Projects, working with more at-risk youth through underwater photography, imparting as much as possible to the next Our World Underwater Scholarship Society Interns. What’s next is looking pretty promising….

Beneath Pearl Harbour is available from Best Publishing. ISBN-13: 978-1930536982

Learn more about the National Parks Service Submerged Resources Centre: www.nps.gov