A Primer on Old Wooden Ships

By Steve Lewis

What kind of dive turns your crank? Cold water wildlife, tropical reefs, shipwrecks, caves… what’s your poison?

Personally, I love cave diving more than anything else. As a kid, caves fascinated me and since then it’s simply grown to become an obsession of sorts. But when asked, “What’s your favourite dive?” in addition to a bunch of cave dives that float to the top of consciousness like cream on top of pail of fresh milk, there are some truly fantastic wreck dives.

The appeal of each type of diving—seemingly poles apart—is difficult to put into a simple sentence. Each has individual character. It’s rather like trying to explain to someone what it is about a couple of friends that makes them friends. Defining their attraction isn’t an easy ask.

One common thread is history. In a cave, that link to history covers tens of millions of years from the warm seas of the Cretaceous to the bones of Paleolithic megafauna. That’s a total blast, if somewhat impersonal. For the vast majority of wrecks, the pages are often blank before the mid-19th century. But the history is there, writ large. Perhaps less mysterious, and more directly human of course, but also a delight and wonder.

I am lucky to live within a few minutes’ drive of the east side of Georgian Bay (Lake Huron), which means I have access to some of the best fresh-water wreck diving in the world. Also, the most varied, from the technical and logistical challenges of Gunilda—a beautiful motor yacht resting on its keel in more than 245 feet (75m) below the frigid surface of Lake Superior—to the soulful vibe of The Empress of Ireland—downstream of Quebec City in the mighty St. Lawrence River as it opens its arms to the Atlantic Ocean.

These two wrecks, like brackets around the east and west edges of the Great Lakes basin, embrace thousands of dive sites in the lakes and rivers between. And all those sites have serious history to tell those of us interested enough to listen.

If you are reading this and have yet to try wreck diving, take this as an invitation. All wrecks have something to tell us about ourselves. To be given the privilege to look at a piece of rigging on a 19th-century wooden ship asleep on the lakebed and think about what was going through some long-dead mariner’s mind as he spliced a deadeye into the end of a piece of rope…well, that stuff appeals to me. It’s a reminder of a collective past.

So yes, wrecks, and the wide-open water under which they sit waiting, have a special charm for this cave diver. And, who knows, it may appeal to you, too.

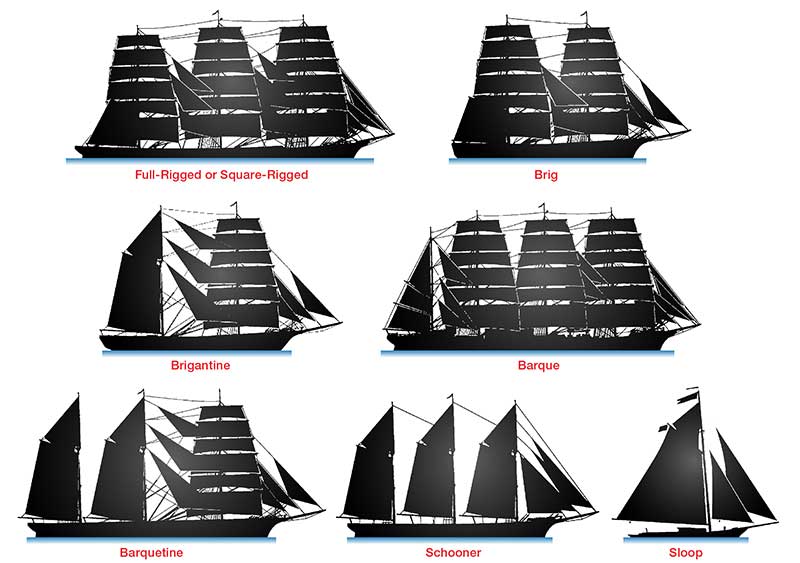

Just in case you’d like to take a crack at sorting out the jumble of wood and rope and bits of industrial archaeology that’s in the Great Lakes, or any other wooden shipwreck site, here’s a quick and somewhat simplified primer on ship’s rigging.

Full-Rigged or Square-Rigged

The classic old-school wooden ship like Nelson’s historic flagship at Trafalgar, HMS Victory, or one of many ‘tall ships’ still sailing today, such as the Christian Radich and Cisne Branco. A full-rigged ship is usually fitted with three tall masts (foremast, mainmast, and aftmast) each with several yards (spars or cross spars) hung on them and each yard carrying a squared-rigged sail, called a yard sail. Each yard sail would be named according to its position on the mast from skysail, at the top, through royal, topgallant, upper and lower topsails, with the lowest being the course sail. In addition, there may be gaff sails on the smaller rearmost mast (the mizzenmast) and stay sails hung between the main, fore, and aft masts. To make life interesting, there would also be as many as five stay sails hung from between the foremast and the bowsprit—the large almost horizontal mast protruding from the bow. A full-rigged boat could carry as many as three dozen sails. These ships were big (commonly more than 230 feet (70m) long), needed a huge crew to sail them, and were used for every conceivable duty, from military vessels to ocean traders.

Brig

This was a much smaller ship, more manoeuvrable and needing fewer crew but still sporting a classic sailing-ship look. The most kids, this is what a pirate ships looks like: two masts, each hung with yards and square-rigged yard sails like a full-rigged ship, but often with a gaff sail aft and stay sails between the masts and forepeak, but fewer bits of canvas than on its fully-rigged big sister.

Brigantine

The other pirate ship. It carried two masts just like a brig but its foremast was square-rigged (yard sails) and the mainmast would be fore-and-aft rigged and easier to manage. There are few if any ships with this complement of sail in the Great Lakes, so perhaps this is not the most useful rig for inland seas.

Barque

The workhorse sailing ship used for every conceivable type of trade through the 1800s. They carried three or more masts but had a smaller crew than square-rigged ships of similar tonnage and were therefore cheaper to run. The aft mast was gaff-rigged (fore-and-aft sails) with yard sails on the main and fore masts. A barque would have been fast and nimble for its size. The Arabia, wrecked off Echo Island near Tobermory, was a fine example of a working barque.

Barquentine

Another large sailing ship usually carrying three or more masts, all of them fore-and-aft rigged except the foremast, which was square-rigged. And again, not a common vessel among Great Lakes shipwrecks.

Schooner

Perhaps the most common type of sailing vessel that worked the Great Lakes. A schooner usually had two masts but wasn’t limited and several famous ships carried more; for example, the Minnedosa had four. Schooners were fore- and aft-rigged with gaff sails on long booms—the tell for a diver trying to work out how a wreck was rigged. One beautifully elegant variant was a topsail schooner, which carried square-rigged sails over fore-and-aft sails on the foremast. The classic schooner also had full sets of stay sails between its masts. (Check out the Blue Nose on the Canadian dime.) These were fast ships, and on the Great Lakes schooners were the jacks of all trades, often used as packet boats carrying goods and passengers.

One of the best-preserved schooners in the Great Lakes is the Cornelia B. Windiate, north of Alpena, Michigan. The first time I dived on her, the sail grommets lay on the deck under the main spar and there were clay pipes, a cut-glass decanter, and coal stacked near a pot-bellied stove in the captain’s quarters. The Dunderberg, another wreck on the Michigan side of Huron near Harbour Beach, is another fine example of a working schooner; however, someone invested heavily in little embellishments and she has some fine woodwork including a beautifully carved alligator figurehead that has a trace of red paint in its eye.

Sloop

If you had a toy sailboat as a kid, chances are it was sloop-rigged. The classic design carries a single mast with one main sail aft and a head sail in front of the mast. There are several variations one carrying a gaff mainsail and gaff topsail aft and the main sail forward.

Steve Lewis is an author, cave diver, life coach and a Fellow of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society. His day-job as Director Diver Training for RAID International keeps him busy, but not too busy to meditate daily using yet another method of focusing his mind!