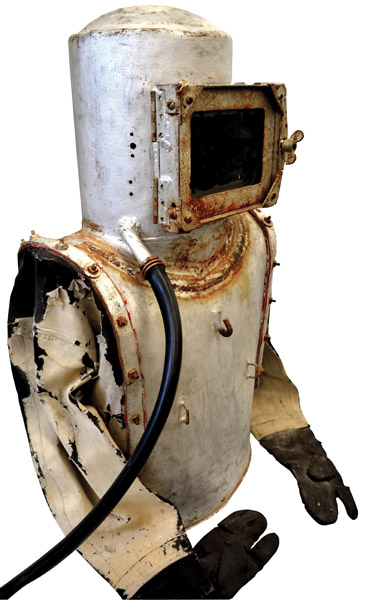

Clam Shell Contraption

In the late 19th century, men wore homemade dive rigs to navigate the muddy Mississippi and other rivers and lakes in a little known ‘gold rush’ for the pearly ‘button’ shells of freshwater mussels

Text and Photography by Phil Nuytten

Cotton may have been King, but freshwater ‘Clams’ didn’t do too bad, either!

HDS-Canada acquired an unusual diving helmet some years ago but was not able to trace its origin until recently. ‘Helmet’ is probably the wrong word: this is more of a diving ‘set’. We now believe it was made for use in the button shell harvest that took place in some major U.S. rivers before the turn of the 19th century, hit its peak in the 1920s, and has enjoyed a sort of a small resurrection starting in the 1960s. What follows is probably more than you wanted to know about the historic American button shell industry.

On March 4, 1858, James Henry Hammond made an impassioned speech before the United States Senate about the superiority of the southern US states – some excerpts:

“Through the heart of our country runs the great Mississippi, the father of waters, into whose bosom are poured forty-six thousand miles of tributary rivers”. A whole raft of blah-blahing follows about the strength of America’s greatest product – cotton. Then Hammond brings it home with: “What would happen if no cotton was furnished [to England] for three years? I will not stop to depict what every one can imagine, but this is certain: England would topple head-long and carry the rest of the civilized world with her, save the South [of the USA]…. No, you dare not make war on cotton. No power on earth dares to make war upon it. COTTON IS KING!”

Hmmm, and we think our current crop of politicians are over-the-top!

“Forty-six thousand miles of tributary rivers” – that’s a lot of water under a lot of bridges and in those waters are (or were) swillions of freshwater mussels, going about their business, snug in their pearly shells. Pearly? Yes, the shells of various species of mussels – or ‘clams’ as they’re called locally – are true ‘mother of pearl’ and are of a quality and lustre comparable to the much better-known pearl oysters found in the oceans of the world. These same so-called pearl-mussels can and do produce pearls in a variety of colours and hues: pink, yellow, black and, of course, a pearly-white. The major commercial value of the mussels lay not in pearls, however, but in buttons made from the shells. Around 1880, there were several U.S. companies that manufactured ‘pearl’ buttons – not from local shells, but using imported ocean pearl-shell as their raw material.

The selling price of pearl buttons was high due to very high price paid for the imported shell (in competition with other international buyers) and the cost of packing and shipping.

Boepple’s Buttons

All of this changed in 1887 with the arrival in the U.S. of a German button-maker named John F. Boepple. In 1885, Boepple received some mussel shells that came from America – given to him by a worker in Boepple’s button plant in Ottensen, near Hamburg. The shells were of a type that no one there had seen before, but a brief test with conventional button tools showed that these strange new shells made excellent buttons. He was finally able to determine the approximate location of the U.S. mussel shell river and a short time later, determined that he would sell his button business in Germany and immigrate to America.

Boepple took a turning lathe and some other trade tools and wound up in Illinois, USA. On the banks of the Sagamon River in Petersburg, he found the shells he had been looking for, and not just on the banks: the bottom of the shallow river was literally covered with mussels! He spent some time exploring various rivers and found that the most abundant shell beds lay in the Mississippi River, near Muscatine, Iowa. The mussels could be harvested with tongs, with drag nets or with ‘crowfoot bars’ (steel bars fitted with numerous lines, each ending in a four-tined, barbless hook). These lines and hooks, when dragged across the partially open shells of the feeding mussels would cause them to snap shut, effectively catching themselves.

All of these means relied on remote operation, but there was another way: diving for them. The advantage of diving was obvious: even in the less-than-crystal river waters, the diver could see what he was doing and his hands were far more effective than the remotely-operated tools. It helped that the mussels were so abundant that a diver could fill and send to the surface many, many bulging sacks in a single day. Diving depth reportedly varied from a few feet to as deep as 60 feet (18m), but usually in the much shallower range.

Boepple and a partner established the first button factory in Muscatine, in the spring of 1891. Once the abundance and the value of the river shells became known, it triggered what can only be described as a commercial ‘gold rush’. A few years later, there were 49 button plants in 13 towns along the Mississippi, along with a dozen near adjacent small rivers. By 1898, there were over a thousand harvesters working between Fort Madison and Sabula, Iowa, with more than a hundred still working the original beds at Muscatine. When the Muscatine beds were nearly depleted, the harvest moved to the north. Lakes also proved to be huge repositories and countless tons of mussels were lifted from lake bottoms fed by rivers tributary to the Mississippi.

The button shell harvest also produced a viable sideline in freshwater pearls, the largest of which sold for extremely high prices. However, this freshwater pearl market and its saltwater counterpart were dealt a near deathblow by Japanese cultured pearls introduced in the early part of the 20th century, an event that coincided with the rapidly diminishing supply of the button-shell mussels.

The button shell harvest continued, but at a much reduced supply rate, and then declined steadily after World War I. The U.S. government shut down a number of the previously productive areas in the belief that they would return to their former abundance given sufficient time.

Clammed Up

By World War II, and the 1940s, commercial ‘clamming’ had virtually ceased. After 1945, and the end of World War II, plastic buttons made their first major appearance and gained instant popularity for their low cost at about one fifth that of a pearl button, for their resistance to breakage and for their variety in any colour, including ‘pearl’. Seemingly, the gold rush was over.

But the Japanese cultured pearls that had damaged the natural pearl mass market became the basis for a complete renewal in the fresh water mussel harvest in the 1960s. A decade earlier, the Japanese had experimented with use of Australian silver-lip oysters, into which beads of other shell material were inserted. The oysters formed their lustrous nacre over these ‘beads’ and cultured pearldom continued. The ‘other’ shell material included trials with fresh water mussels, which turned out to give the best results by a high margin. Cultured pearls could be produced that exhibited a superior quality and in a significantly shorter time by using Mississippi ‘clam’ beads and the old button-shell industry came back to life in a newly invented role.

Today’s SCUBA-based harvest of fresh water mussels is a fascinating story in itself – one which I’ll be glad to relate, but not today!

Back to the Mississippi button shell diving outfit, circa 1925. Virtually all of these early surface-supplied rigs were homemade contraptions and few survived. HDS-Canada is fortunate to have a professional ‘picker’ as a member. Jeff Harris was browsing through antique fairs and flea markets in the southern states when he came across this piece. He called me, described it in detail and I said, “Grab it!”, which he did. We are very pleased to have such a rare piece of ‘Diving Americana’ in our collection.