Dining Out with Sacred Cows

He’s not a shark expert, hasn’t studied their behaviour, and doesn’t champion their cause, although he was once bumped by a shark not looking where it was going. Good job our man Sawyer doesn’t bear a grudge.

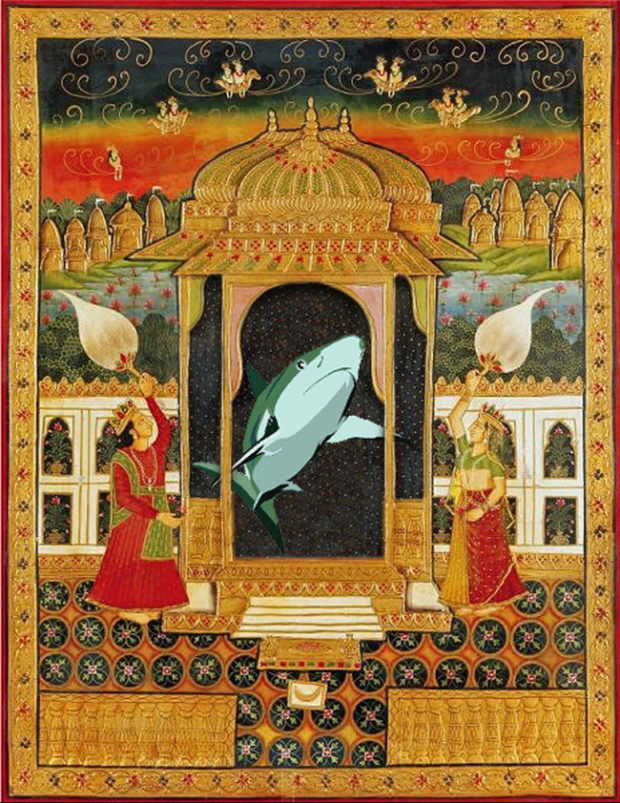

Text by H.E. Sawyer – Illustration by Peter Dahl-Collins

I’m sorry, but I don’t care about sharks. I never have, and I never will. Admittedly they’re a strong graphic for a T-shirt, although I don’t get a smug buzz when a percentage goes toward their welfare, because I care about shark conservationists even less.

There’s a sense that because I dive, I’m expected to sign up for sharks. Maybe that’s because if shark activists can’t count on divers for support, who can they rely on? I’ve been considering this diver-shark shark-diver relationship ever since a ‘discussion’ I had last year, with a Scandinavian in a tinpot airport, waiting for planes that would probably never arrive.

We were surreptitiously trying to trump each other with our daring-do when I casually mentioned how I’d be open to an ‘interactive’ shark feeding experience and got an ear full in return.

In summary, feeding changed shark behaviour, he was a marine biologist, so therefore he knew!! He definitely used exclamation marks. One of us was standing his ground, and one of us wasn’t, because thankfully my flight was boarding.

Punch Up

Views on the controversial subject of shark feeding are polarized: conservationists in one corner, business interests in the other. Rank and file scuba divers pick sides, then there’s an ideological punch up, and although I don’t give a monkey’s about sharks, I don’t want to miss out on the opportunity to goad everyone else on.

It’s no real surprise to discover that there’s not a single marine conservation group that supports the idea of feeding sharks. Most suggest it changes behaviour, distribution, feeding patterns, and the nature of the shark’s contact with man.

Instead of patrolling a large habitat for food, the easy pickins’ of staged feedings may cause sharks to stay in a smaller area and in closer proximity to more of its own species than would occur naturally. Feeding opponents fear sharks will become dependent on ‘hand outs’, and may graze rather than hunt. Conservationists worry illegal shark fishing could take place at designated feeding sites, once the diving audience has left for the day.

In 2001, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission introduced an outright ban on feeding marine life, after a group of divers, (the Marine Safety Group), lobbied for action, having experienced an increase of intrusive sharks expecting food.

There were growing concerns that the feeding and baiting of sharks, by diving operators and underwater photographers, was leading to an increase in shark attacks, although incidents have continued since ban implementation. And there’s nothing to suggest that controlled interactive shark dives will be any safer after the first fatality in the Bahamas in February 2008.

Of course shark attacks of any description are rare. The familiar refrain: “You’re more likely to be struck by lightning than attacked by a shark.” Well, obviously. The lightning strike audience is orders of magnitude larger than the potential shark bite collective.

Truth is, while we paddle, swim, surf, dive, capsize, or wade across the Zambezi, we’ll have incidents. And regardless of the risks, divers will want first hand experiences, although conservationists maintain actual encounters are not a prerequisite to encourage shark protection. They claim most divers would prefer a genuine interaction to a staged ‘circus act’.

Dermot Keane of Sam’s Tours, and founder of the Palau Shark Sanctuary agrees. “Shark feeding not only endangers divers and snorkelers but also interferes with the sharks’ natural survival behaviour. One of the beauties diving Palau is that shark sightings are all but guaranteed on every dive. There’s no need to feed sharks in Palau.”

Dermot is a true Patron Saint of Sharks. But it’s easier to take the moral high ground when your desk is 50 minutes from ‘Blue Corner’, and other sites, where shark encounters are pretty well a given.

Size Matters

So what are the arguments for and against?

Supporters of feeding subscribe to the view that shark shows generate dollars, which boost local economies, making the shark worth substantially more as a live performer than as dead meat. You have to hope that this revenue does indeed filter through to the local community since ‘their’ sharks are financing the operation.

Opponents say sharks contribute to tourism whether they’re being fed or not. But ultimately, do not the raves and recommendations – and return visits – depend on how big the shark is in the diver’s viewfinder?

The Bahamas’ shark feeding frontrunner, Stuart Cove, believes they’ve learned a lot about sharks thanks to the close observation feeding affords, including which food sharks prefer.

They make the point that other than providing a food source, they do everything possible not to interfere with natural shark behaviour, allbeit that the food source is the issue.

There’s no scientific consensus regarding behaviour modification as a result of feeding, although you sense that particular dissertation is just around the corner. According to PADI, numerous scientists do not endorse the idea that feeding experiences are harmful, though the identity of these scientists remains unknown to me. But to the point: harmful to sharks, to divers, or both parties?

The 2009 death of a French tourist snorkeling at St. John’s reef in the Red Sea immediately was linked to a suspicion of illegal feeding in the area even though the incident occurred during a natural encounter. An incident statement from the Hurghada Environmental Protection and Conservation Association, (HEPCA), referred to the practice of shark feeding in the Caribbean apparently for no other reason than to imply that the Red Sea was ecologically responsible, the Caribbean was not. Sadly, that’s the nature of the debate, or the importance of tourism.

How the effects of feeding sharks will play out long term is uncertain. Sharks are difficult to study because they’re free ranging, though this contradicts the fear that they’re simply circling man-made auditoriums until show time.

Dr. George Burgess, director of the International Shark Attack File in Florida, opposes feeding. “They (sharks) lose their natural caution around human beings. For the same reason on land we don’t feed alligators or bears.”

The Birds And Bears

He’s right of course, although I’ve seen sharks and bears in the wild, and trust me on this, they’re completely different. For starters there’s nothing to stop a hungry Yosemite bear bowling down the main drag looking for left overs, whereas I think we can be confident no shark is going to come thrashing up the beach at Nassau after barbecued tourists.

Comparing a shark to a bear is like comparing both these animals to birds.

We feed birds and change their behavior. Birds are literally our canary in a coalmine. They give us an accurate visible reading on the health of our environment, in a way sharks and bears cannot.

Consider that we rip up hedgerows, fortify our towns and cities with nine-inch nails, domesticate cats, and spray pesticides. Birds control insects, rodents, and distribute seeds. And although they don’t do it for our benefit, they sing their bleeding hearts out.

With the blessing of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds – arguably the U.K.’s most successful conservationists – I can learn how to attract multiple species to my garden with a variety of sustainable foods in different bird feeders. I can learn how much to feed, when to feed, and the importance of feeding hygiene. Putting food out for birds has been proven to strengthen populations. It is unquestionably a good thing to do.

The British have been feeding birds since the newspapers suggested it during the harsh winter of 1890-91. Within 10 years bird feeding was considered a national pastime. It’s now one of the fastest growing activities in America, where some 55 million people – 18 percent of the population – regularly indulge.

Yet remarkably, they always fly away when I open the door – after feeding them for 20 years. The starlings regroup on the chimney pots to slag me off. Feeding has not changed their behaviour to the extent that they’ve sacrificed self-preservation or self-sufficiency when I’m away on holiday, for that matter. While it’s clear that feeding bears would be foolish, it’s evident that birds have developed a symbiotic relationship with us, solely on their terms, and they have benefited as a result. So have we.

I’m not suggesting that what applies to birds will necessarily apply to sharks, but if the reason for not feeding sharks relies on the comparison with bears, then we need more research and to be open to all considerations.

What’s More Deadly?

Ah, I know what you’re going to say. Sharks and bears can kill you, and birds can’t. Not so fast. According to the World Health Organization, H5N1, the viral strain of bird flu, has killed more than 250 people since the first human cases in 2003. For the divers who might scoff, it’s worth noting that 26 of those deaths were in Egypt.

According to the International Shark Attack Files, there’ve been 464 deaths. Since 1958.

So, statistically, diving with sharks, ‘tamed’ or otherwise, was less risky than being sneezed on by a Kowloon duck; unless you’re going to let testosterone suggest that death by bird-bug somehow isn’t as worthy as being ripped limb from limb by a ferocious fish.

In nature the prey outnumbers the predator, although shark conservation groups are hardly rare. Perhaps it’s the ‘glamour’ of apex predators that’s lacking in rarer species lower on the food chain, turtles let’s say, that are part of the shark’s diet. We can only hope that if sharks survive, they won’t have to rely on our handouts, because activists were too busy saving them at the expense of what they’re supposed to eat.

Sharks have been around for 400 million years, so there’s no need to patronize them. They were outwitting sea monsters long before we evolved, and hopefully they’ll be swimming the oceans long after we’ve gone.

They’re not doe-eyed orang-utans, clinging on for dear life in a diminishing jungle. Conservationists estimate annual shark kill at about 70 million worldwide, so playing devil’s advocate the animals must be doing something right for there to be such abundance to kill every year

If staged feedings change shark behaviour, because it suits the shark, they might not only survive but also thrive. Ring fencing sharks around artificial feeding grounds may be unnatural, but if you believe conservationists then something radical needs to be done.

There’s no point waiting around for us to control our fishing fleets so that we can share the seas harmoniously with sharks, because it’s highly unlikely we’ll modify our behaviour until it’s too late. Blue fin tuna anyone? The shark simply cannot trust us to do the right thing. Not that it ever has, or that it ever will. I’m no expert in shark behaviour, but I suspect they don’t give a monkey’s.

FIN