Exploring the ancient mine that made Greece a superpower

“Old things become new with the passage of time” – Greek Proverb

Words by Maria Fotiadi, Erikos Kranidiotis, Stelios Stamatakis

The mines of Lavrion: a vast complex of tunnels, covering more than 46 square miles (120km2), that has produced unimaginable quantities of silver, lead and copper throughout the centuries.

Mining activity began in this Greek landscape as early as 3000BC, when copper was extracted for the construction of early Iron Age tools and weapons. Later, lead and silver became the main focus. So it was for centuries, peaking during the 5th century BC during the Athenian Republic. The ancient mines were instrumental in the construction Acropolis of Athens and the formation of the mighty Athenian fleet, which made Athens a superpower of its time.

As the influence of the Greek Empire receded, the mines fell into disuse. Then Lavrion again became important to the economy of the Modern Greek State, after its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1821. Mining continued here until the 1980’s when, due to the de-industrialization of Greece, the mines ceased production.

Shortly after, Lavrion became a large archaeological park and an industrial heritage site. Archaeologists, mineralogists, and geologists visited the site to explore and conduct research in their respective fields; but there was a limit to this access. Deep vertical shafts, muddy terrain, semi-collapsed arcades and long distances to reach the heart of the mine made the task more demanding. And then there was the water. Everything stopped where the water began.

Thirst for exploration

The inflow of water from the aquifer had been a frequent problem during the working life of the mines. Where it was impossible to continue mining by pumping out the water, galleries were abandoned or sealed. Water flooded the lower levels, making them inaccessible. This prevented modern visitors from accessing these lower levels, protecting this section of the mine from acts of vandalism, an unfortunate occurrence over the years. The rediscovery of such a flooded area by a group of dry cavers and the desire to explore further led them to contact the Addicted2H2O diving team to explore these galleries.

Our first meetings took place in May of 2019. The team visited the first site, the Hilarion complex, in the Kamariza Region near the modern village of Agios Konstantinos, to evaluate the logistics of exploration. Accessibility was going to be difficult. It would be more than an hour descent via slippery terrain, down to the 5th flooded level of this enormous mine site (400 ft/120m below ground level), to stage the dives. There was no existing infrastructure to transport the diving gear. Our team was going to have to do some serious heavy lifting. But we were excited and ready to pull this off.

Less than a month later, in July of 2019, we made the first exploratory dive. The site was amazing. The water was warm, almost 68°F (20oC), and the visibility of the was exceptional. Starting our underwater descent in a huge excavated chamber that had become a subterranean lake, we saw the first tunnels. Wooden beams, railway tracks, and graffiti left on the walls by the miners gave us a taste of what was to come.

A second exploratory dive took place at the same mine complex a few months later. We explored fully the three different passages that we had initially encountered and found them to be interconnected; but there was a fourth passage with an impressive rail track from the 1930s that was enticing. It might also work as an alternative exit.

Sure enough, the Hilarion mine had more secrets to reveal. Another area, Number 50, was also flooded. (In the last century the mining company had assigned numbers to the various tunnels.) Mine 50 was part of the ancient mine, which later had been exploited and expanded, and it remained in use from the 1870s until at least the 1950s until groundwater from the aquifer flooded and cut off the lower levels.

Our team visited Mine 50 on January 4, 2020. The dry part of this mine was also impressive. Due to the high humidity, especially near the flooded section, metal and metal oxide formations have created a beautiful, colourful spectacle. Aragonite, copper, hydroxides, and malachite are some of the many minerals in the gallery. Graffiti from the 1920s and 1930s also covers the tunnel walls.

Underwater, rail tracks for the mining wagons remain almost frozen in time. A mining basket left in place by the last miner and the large mechanism that pulled the wagons were still standing as an impressive momentum of a long-lost era. You could almost see the ghosts of the workers, still toiling to extract the valuable ore. It was clear that we were just scratching the surface of this unknown world.

Tunnel 80

This project would not have happened without the right people to help us. Vasilis Stergiou was an invaluable asset; exploring the mines for years—since he was a child—he knew how to navigate the maze of tunnels. Vasilis probably had spent more time in the mine galleries than in the real world! His knowledge of the Lavrion district was deep (no pun intended) and every time he joined us to show us a new flooded section, he shared generously information on and stories of the mines. The diving team was assisted also by fellow divers and dry cavers, who willingly joined us at this quest: Apostolis Tzamalis, Trifonas Egglezos, Akis Pallis, Kyriaki Fosteri, Konstantinos Kalomoiros, Panos Karoutzos, and Georgia Manzi were the valuable support team. The commitment of the support team allowed us to further the exploration of new flooded sections over difficult terrain.

Located just four miles (6km) from the modern settlement of Lavrion and its port is the village of Plaka. It was the second largest mining center in the region and the largest mining complex on the northern side of Lavreotiki, with extensive mining facilities. Plaka surpassed the Kamariza mines as a center of production and had a greater variety of ores, including mixed sulphites and manganese. The successful extraction of the ore led to the construction of mining shafts and other infrastructure, and the mines were worked from 1885 through the 1970s. However, in many parts of the mine, the issue of the rising water created such a difficult obstacle that some tunnels were abandoned even though the ore deposits were still rich.

Our team visited the Plaka region from July to December 2019, conducting multiple dives in four different dive sites. In almost all of the mine sites, the transportation of our diving equipment was challenging. But there was one specific dive site that was a real nightmare: Mine Tunnel 80.

Plaka is a huge mine complex, with hundreds of miles/kilometers of tunnels. Tunnel branches radiate in every direction and there are some serious heavy installations for delivering a vast amount of ore. During the 1950s there was a need to find new profitable mineral sources. This led to the extraction of the ore at Mine 80, which was opened between 1954 and 1956. Main purpose of Mine 80 was to unite an extensive area of mine tunnels at the north and the south part of the Plaka Mine Region, covering a mile (1700m) in length. It contained an extensive railway system of wagons and heavy machinery to transport the ore, as well as a power station for electricity. Many shafts inside the mine reach a depth of 500-525 feet (150m-160m).

Extreme challenge

Mine Tunnel 80 was by far the most extreme and challenging mine that we have ever been through. Although we had a support team of only three individuals to carry four 80 cu.ft. tanks each, along with all of the other necessary equipment, the team undertook a very difficult 50-minute descent into the heart of the mine to stage for the dives. The dry part of the tunnel was a nightmare, with semi-collapsed arcades and silt covering the floor, a bad sign for the of the condition of mine. The substrate was mainly soft slate, which had led to the inevitable collapse of many passages, even during the time the mine was in operation back in the 1950s. This meant there were numerous wooden columns and support walls built out of stone that had been erected to keep the roof intact. If the dry part was in such condition, we could only imagine how it would be underwater. After a steep and slippery descent that reached over 330 feet (100m) in depth, assisted by rope in a couple of extremely steep parts, the team reached the dive location.

The state of the mine underwater was extremely poor: a more-or-less collapsed tunnel with similar characteristics to the dry parts above. Wooden beams and stone walls supported the roof. Visibility was very poor; effectively zero at the start of the dive, although it started to get better slightly as we progressed further. The water was colder, at 60°F (16°C), and percolation affected the visibility and caused pieces of silt fragments from the roof to rain all over us. We explored three different branches of the main tunnel. All had further galleries splitting into different directions. Many parts had collapsed. It was by far the most dangerous part of the whole expedition. There was only one way in and out, and the poor visibility made the return an extra challenge. It was a chilling reminder that diving in an overhead environment such as a mine can be unforgiving.

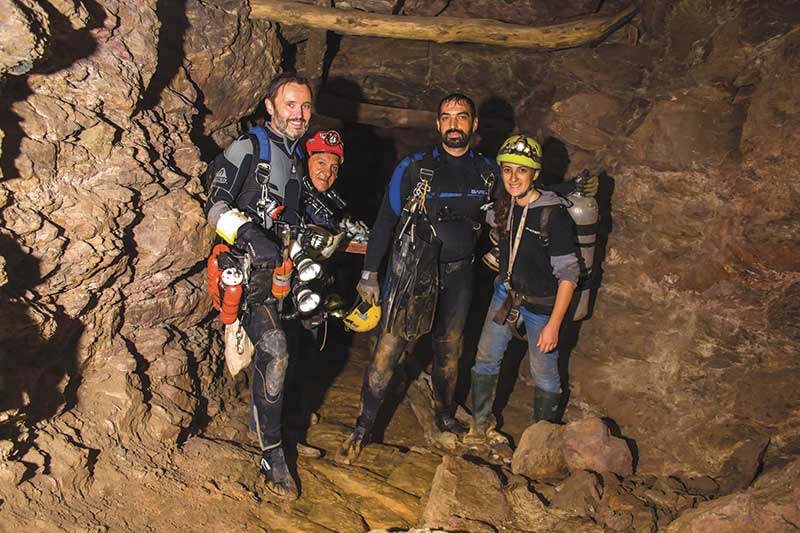

the team from Addicated2H2O. Photos courtesy: Addicted2H2O.com

Unexplored

Mine diving in many countries is a regular form of technical diving. Mines in Europe, for instance, are explored and carefully prepared to be safe dive sites, open to the public and visited by those with appropriate training and experience. In Greece, that is not the case. While some of the industrial buildings from the mine’s heyday have been preserved, the mine tunnels remain mostly unexplored. They remain unmapped to a large extent and unfortunately are easy prey to acts of vandalism. But water sealed some tunnels and these underwater passages may offer an opportunity, as a time capsule, to see the mine as it was at its very last moments, before the workers abandoned it.

Further exploration is the main objective. With this mine exploration project, the team hopes to pave the way for future explorations and share the unique images of this underwater quest with the wider public. After all, Lavrion is one of the oldest and iconic mine sites in the world. Maybe one day, these mines will open to the public as museums of industrial heritage and the flooded sections could become a new exciting diving spot for technical divers.

For more information about the exploration visit the official site: www.addicted2h2o.com

Leave a Comment