Fish or Plastic: Our Changing Oceans

By Jean-Michel Cousteau and Holly Lohuis

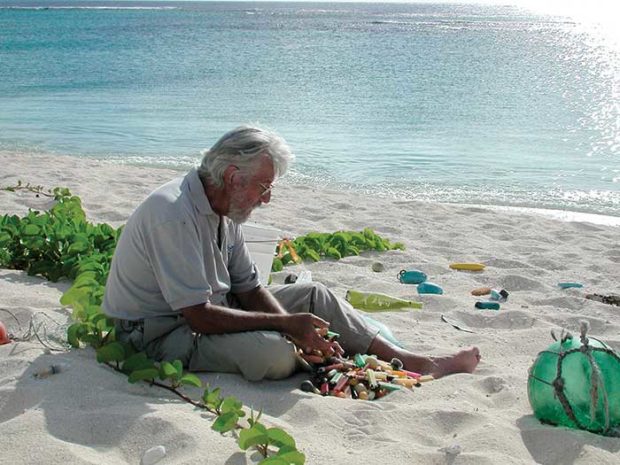

In the middle of the central Pacific lies a string of islands, atolls, and submerged reefs that provide a haven for a rich array of marine life. Here, in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, the oceans are full of healthy corals, huge schools of apex predators like jacks and sharks, and millions of nesting seabirds made up of over twenty different species. When I first explored this remote part of the world with my team back in 2004, I thought the inaccessibility of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands would protect these remote places from the worst of humanity. But I was wrong. When we walked the isolated beaches of Laysan, Midway, and Kure Islands, we came across the scars of our wasteful “throw away” world. We found plastic trash and marine debris scattered everywhere, including inside the bodies of dead, decaying seabirds. Picking up a dead Laysan Albatross carcass and seeing dozens of plastic items fall out of the stomach of the bird is a sight that will remain etched in my memory forever.

Many of the world’s seabird species need isolated, undisturbed islands to nest and raise their young. They need access to a productive ocean where they can hunt both close and far away from their nest. Albatrosses are known to fly tens of miles, even hundreds of miles, out to sea in search of rich and nutritious oily meals of squid, fish, and fish eggs. Unfortunately today many seabirds are mistaking floating plastics for what they believe is a delicious meal. Instead it is a deadly one. Once the bird swallows the pieces of plastic, it will fly back to its nest to regurgitate the items to their hungry chicks, unaware of its dangers.

On Midway Island alone, there are over a million albatrosses that nest in very close proximity to other nesting pairs, all on a small landmass less than 2.5 square miles (6.5km2). As you can imagine, the sight of almost 450,000 nesting albatross pairs makes Midway Island one of the most spectacular bird colonies in the world to witness. Unlike most seabirds that lay their eggs in the spring, Laysan and Black footed albatross do so in the winter, maximizing the extra long hours of darkness to forage out at sea. By the time my team arrived on Midway Island in July, most of the chicks had fledged and taken off to the sea to forage like their parents, and island bird life was at a lull. But we did witness what was what was left behind from all the nesting activity – the plastics brought in from the sea to the island by the adult birds in an attempt to feed their rapidly growing chicks.

Microplastics

Plastics have been around for over a hundred years. They have helped us advance the convenience of our society. In the 1950s, post-war, the mass production of plastics that we know today took off. From the best of scientists’ estimates, over 9.2 billion tons of plastic have been created in the past 70 years. Of that, more than 6.9 billion tons have become waste and less than 10% has ever been recycled. So where is all this plastic waste? Scientists are learning more about what has been feared for decades: much of this plastic waste has ended up in our waterways and oceans of the world. Over the decades, plastic waste has accumulated in large oceanic currents and gyres where the wind, waves, and sun break down the plastics into smaller and smaller pieces, but it never “goes away”. These smaller pieces are referred to as microplastics. They are so tiny that it can be hard to see them with the naked eye. But they exist, everywhere, and other animals often mistake them for food, allowing plastics to accumulate in marine life and make their way up the food web – where eventually, we may be eating them, too. Everywhere humans look in the ocean, from sediment samples in the deep seas to remote polar-regions and beyond, our plastic waste is found.

More plastic than fish

But do these long-lasting plastics that may take a thousands years to degrade need to be used for our single-use items such as straws, bags, and water bottles? Single-use plastic means just that…single use. We know now that these items do not go away when we throw them in the trash. Instead, it will take hundreds, if not thousands, of years to disappear. That is if they actually disappear at all. This exponential growth of plastic we are witnessing in our oceans and waterways is now being well documented and studied. And the more we study it, the more some scientists are sounding the alarm bells to tell us about their grim predictions: there may be more plastics in our oceans than fish by 2050.

How have we let this happen? Now that plastic pollution is making headline news all around the world how can we, as divers and citizens of our ocean planet, do more to support dive operators and ocean tour companies who are addressing this issue and removing single-use plastics from their operations? As consumers and ocean enthusiasts we must encourage all aspects of the dive industry to address this growing impact affecting our favourite dive destinations. I feel an immense sense of hope after recently returning from Fiji, where I enjoyed my favourite drinks served with paper straws. I applaud the many companies, cities, states, and even countries that are banning single-use plastics. But we do not need to wait for legislation to be passed; we can all do our part and travel with our reusable water bottle, bamboo cutlery, and metal straws, taking actions any way that we can to show decision-makers and our leaders that we want a world with no plastic waste.

We know the ocean is resilient; nature comes back when we give her a chance to heal. There are many threats that impact the health of the oceans today, but by removing single-use plastic from our everyday choices, we can all be a part of a very easy and solvable problem. It all starts at our fingertips with what we choose to buy and what we choose not to buy. We all need to become involved in ocean stewardship. There has never been a time when it has been so critical to participate in ocean conservation.