Interstellar Connection

No fanfare. No quest for glory. Just the unshakable conviction that a fetid pond would open onto the heavens

Words and Photography by Cristina Zenato

The foul smell from the little pond reaches my nose as I settle the tanks on the water’s shallow rocky edge. It is created by the lush half-submerged vegetation brewing under the hot Bahamian sun, mixed with some other ingredients that I am not

keen to discover.

This cave entrance is known as Mermaid Pond and it sits right in the middle of the native settlement known as Hawksbill on Grand Bahama Island. I heard stories from older local people of when the water was so clean they could drink it. That is no longer the case, and it hasn’t been for quite some time.

I come here to explore the system and show the connection between this land hole and the ocean hole known as Chimney. I have been told that the two cannot connect; several explorers have attempted it without a positive outcome. In his famous book, The Blue Holes of The Bahamas, Rob Palmer defines the Chimney as “One of the most dangerous of caves,” and that, “It is terrifying.”

Looking at the map, I cannot believe these two holes are not somehow connected, and I am determined to find the way.

Mermaid

While I am here working on the exploration and mapping of the system, I am used to attracting a lot of attention and a crowd. Some people believe an actual mermaid is living in this cave, and I am in harm’s way by entering her kingdom. Some locals question why I would want to submerge under dark water that smells like rotten eggs. They believe I am diving here because I have found a treasure I do not want to share with them. Diving here makes for quite a few amusing stories to share at dinner.

Today, an old lady approaches along the walkway; she is dressed in an all-white cotton dress and matching turban, carrying a straw bag. Her body is small and thin, and her skin is dark and wrinkled. She seems to have lived a hundred years. She stops, puzzled by my presence, and asks me what I am doing. I explain to her that I will dive under the rocks she is standing upon, and I will attempt to surface in the ocean, in the blue hole located five hundred feet (150m) from the beach.

I continue to explain that if I can swim from one to the other, I could demonstrate how water moves and, with it, the fact that both nutrients and pollution use these passageways as a conveyor belt.

If it could, her face would wrinkle even more under her concerned look. She takes a few steps, comes closer to the water, and sits on a tree downed by long-gone winds. In her creole accent, she states that what I am about to do is very dangerous, so she will sit and pray for me until my return. I thank her profusely, but I explain that my dive is going to be between two and three hours, that I have been here before, and that I am highly trained.

No matter the explanation, she decides she has to sit there and wait for me. I thank her once again and submerge. I am sure she will grow tired and bored and leave after fifteen minutes.

Three hours and twelve minutes later, I surface. To my surprise, the lady is still there, holding on to her purse. When she sees me, she says, “Good! You are back, may God bless you”, gets up, and leaves. I am still in the water, clad in piles of gear and slightly wordless; I say a quick thank you and smile as I watch her walk away.

Project 2020

This exchange occurred nearly ten years ago in 2012 while I was working as an active contributor to Project 2020. Project 2020 was an initiative issued by The Bahamian government to protect an additional twenty percent of The Bahamas territory under Marine Protected Areas (MPA) by 2020. The campaign enlisted experts from each island who were passionate about tourism and the environment, in order to select, highlight, and present a full brief on the areas deemed of interest for protection.

As the only cave diver on the island, I was approached and I agreed to work on two major areas: the Lucayan National Park with the famous Ben’s Cave and Sweetings Cay, a small cay off the east coast of Grand Bahama with a complex system of caves known as the Zodiac system. While Hurricane Dorian and the following COVID-19 crisis delayed the outcome by a year, we are currently back on track, and the Bahamas National Trust has submitted the proposals for review.

In the Bahamas, where I have resided and worked for the last twenty-seven years, we have many caves, both inland and in the ocean, known as blue holes.

These caves serve numerous purposes. The highest point above sea level in our islands is 207ft (63m), Mt. Alvernia – Cat Island. We are a country without rivers, lakes, mountains, or snow, and yet there is drinking water coming out of our taps. The limestone composition of this archipelago allows the rainwater to filter through the rocks and deposit itself on the top of the saltwater level. The Bahamian caves are an immense, but not unlimited, reservoir of freshwater supply. While the limestone is a natural filter, pollutants dumped on the ground can disrupt its integrity. As a consequence, the water table below becomes highly vulnerable to damage and destruction. Once the filtering capabilities of the rocks are compromised, particles of different origins can find their way into the aquifer.

Heavy development on the land directly above the caves, with consequent pollution of the area, causes extreme damage to the water table.

Chimney

While Mermaid Pond was not part of the conservation effort, I wanted to show how the development had compromised the reservoir and destroyed the related ecosystems. I had already proved the high level of pollution inside the cave by collecting water samples indicating the presence of the dangerous E.coli bacteria, among others. Still, I wanted to show how it could travel to the ocean by connecting the two entrances. The water conditions on the side of Mermaid were terrible; black water, excessive levels of microbial growth disturbed by my passing made the exploration slow and difficult. I found leading passageways heading north; as I moved further away from the settlement, the conditions improved; however, all of my attempts to head south towards the ocean proved unsuccessful and, at times, extremely dangerous. I decided to continue the attempts from the ocean side, where the water conditions were ideal. Unfortunately, picking that route added a series of issues to address. The ocean blue holes are tidal, meaning they siphon and blow water on a six-hour schedule, repeated four times per day with a slack time of twenty minutes in between each cycle. The Chimney entrance is a 40-foot (12m) deep shaft, six feet (2m) in diameter. When the tidal force blows the water out, the ocean’s surface looks like a boiling pot. To enter, I had to wait for the twenty-minute slack tide to progress in far enough to avoid being caught in the outgoing flow. As the tides experience a cyclical delay, the slack periods rotate, presenting the slack either in the middle of the night, too early, or too late in the day. During these times I could not access the cave and continue my work.

Furthermore, I needed comfortable ocean surface conditions to wade to the entrance with all the gear in tow. Last, but not least, I had to match these two conditions with my available free time. I continued my efforts, although at times the cave seemed to resist my attempts.

On December 31st, 2012, I submerged for a final exploration dive and surfaced in Mermaid. I carried a total of four tanks. I called a friend who rushed to the site to document the event, then I swam my way back to the ocean to find a warm cup of coffee and a few shocked locals an hour and a half later.

Using this system as an example would finally serve as essential leverage to push the protection of Ben’s and all the surrounding land, as it was still untouched and in pristine condition.

Sweetings

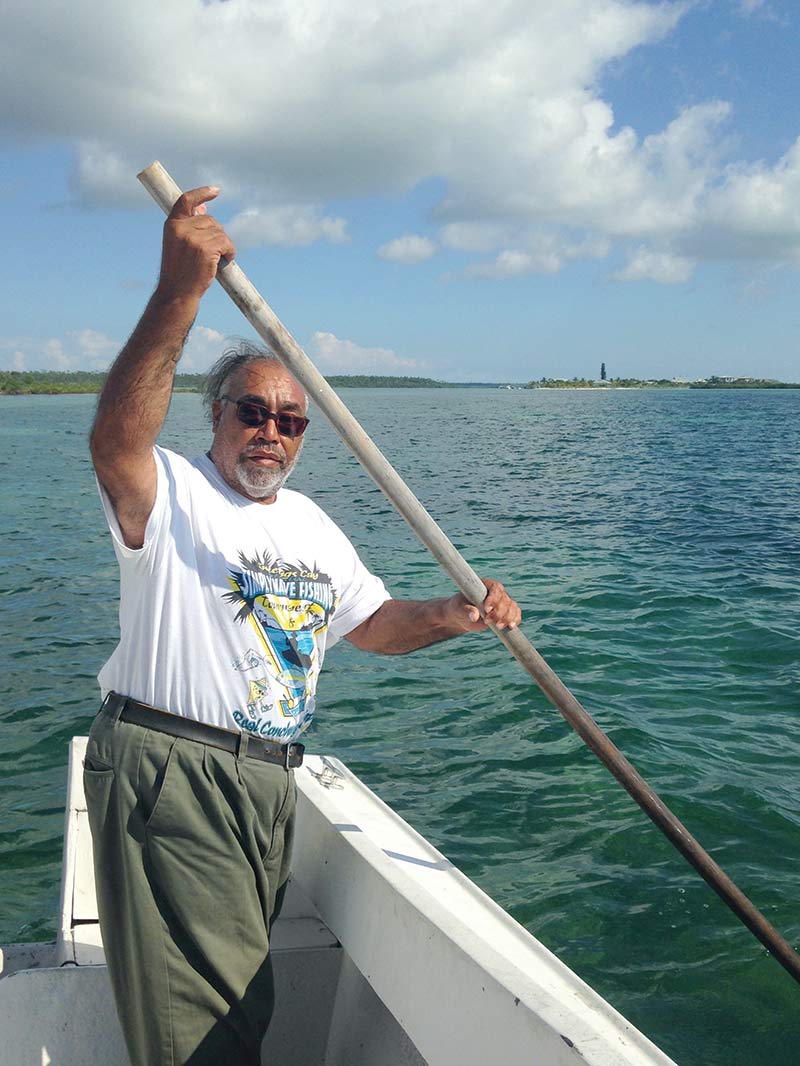

At first, I worked in parallel between Ben’s Cave and the Mermaid Pond-Chimney systems. When I completed the entire survey of Ben’s, I continued to work on Chimney and turned my focus to the Sweetings Cay area. This area required additional investment and planning. The Cay is located off the east side of Grand Bahama. To dive Sweetings, I would organize my car the night before, leave at 7 am, drive an hour to meet a local boat captain, Doral Puyform, to ferry me over. After offloading my car into the boat, and a thirty-minute ride to the Cay, I would take three to four round trips across uneven terrain for about 400 yards (365m) each trip to carry all of it to the water’s edge. The final step was a 300 yard (275m) swim across a saltwater pond. After two to three hours of diving, I would surface to complete it all in reverse. I was able to make one trip per week, usually on my day off.

Known as the Zodiac system, this area comprises six different cave entrances with names from the Zodiac. The map of Aquarius, Scorpio, Pieces, Virgo, and Sagittarius, when compared to the surrounding land and the saltwater depressions, indicate that they were all part of a massive system. Most likely during the ice age, parts of the system collapsed for the lack of support from the water, isolating one section from the other. Once again, I had read about these caves from the original explorer Rob Palmer. Visiting them almost thirty years later gives a glimpse into the incredible work these explorers completed with the gear and technology available back in those days. They didn’t finish their work, nor I have yet to finish mine.

Connections

In 2015 as I was surveying one section of Gemini, I discovered a leading passageway. It would take me away from Gemini and open the cave to additional thousands of metres of lines. These systems present three levels, with fractures and fissures to squeeze through, allowing exploration at thirty metres, twenty metres, and sixteen metres (98ft, 65ft, 52.5ft). During one of my explorations, I squeezed into a chamber at thirty metres (98ft) and there, alone, I found an original piece of exploration line from Rob. After three dives, trying to figure out how the line arrived in that location, I decided that the line was coming from a different direction. I realized that there was another missing connection. I headed to the closest cave entrance, Aquarius, which I had not checked out yet, to find a solution to the mystery. On my first dive in Aquarius, I could also see the original exploration path while laying my line. I followed it until I felt it was going towards an incorrect direction. Then Palmer’s line continued deeper and deeper towards that thirty metre (98ft) mark, but after months of exploration, I knew the cave would stop at depth. Instead, I looked up—something I had found very useful to do while exploring this system. Above me, there was an opening; I swam five metres (16ft) up to find a plateau and another descent into a corkscrew back down to thirty meters (98ft); then ascended again. In front of me was my exploration line from Gemini. I connected the two lines, swam one direction to verify the correctness of the exit, then traced back. Doral was waiting for me at the entrance of the creek leading to Aquarius.

I returned the following day to complete the traverse while surveying the new line. A skeptical Doral dropped me off at Aquarius with instructions to drive back to his home on the other side of the Cay and wait for me there. It was October 2015, and I swam from Aquarius to Gemini, then walked my way back to the dock as I had done many times before, connecting these two systems thirty years after Rob Palmer started. I called the connection the Interstellar Tunnel.

Puzzle piece

Subsequently I would solve the mystery of the little piece of exploration line I found from Gemini. Reading Rob’s book showed that he had continued deeper into Aquarius, jammed himself into an incredibly tiny area, and bailed out; in the process, he cut the line and left it there for me to find so many years later.

Before Hurricane Matthew hit in 2017, I completed the survey of all existing systems and added a copious amount of exploration.

This year I was able, with the help of Kewin Lorenzen, to resume the work in Sweetings. This Cay has a special place in my heart.

Preservation

The caves at Sweetings all have entrances by ocean creeks or mangroves areas. Mangroves are nurseries for marine creatures, from invertebrates to sharks and bony fishes. In these areas, the animals reproduce, allowing the young to grow protected from the larger predators. The Bahamas have been a shark sanctuary since 2011. After a few years of work, we convinced the government to vote to protect all species of sharks within our waters. Protecting sharks goes beyond protecting the animals themselves. We also have to preserve their food and where they reproduce.

Many species of sharks are inhabitants of the mangrove areas during the first stage of their life. When the pollution travels through the rocks and hits the water, it also follows the path of the water itself, reaching everywhere these passageways reach. The work at Sweetings concentrated more on this aspect of conservation and preservation.

Caves are also the keepers of important history at a geological and anthropological level. In one of our most recent works, we found several crocodiles’ impressive remains, extinct from this country several thousands of years ago. In Ben’s cave, human remains belonging to the original inhabitants of these islands lay hidden in the hypoxic level of the cave, out of reach and out of view. Should the water conditions change, their preservation would be affected, and their survival compromised.

Knowledge

Exploration is a very compelling word. It opens our minds and imagination to never-seen places, undiscovered information, and ideas of pursuing something beyond the ordinary. Exploration is a series of repeated attempts, failures, dead-end tunnels, and small areas leading to nothing.

These moments will only build another essential tool for the aspiring explorer: knowledge and understanding. Each time we attempt a route, with either a successful result or not, we collect data in our brain on how the cave works.

People say that cave exploration follows the 10% rule; we will find a good one for every ten attempts. I have floated at the edge of the 1% rule, and I have yet to give up. Exploring in the Bahamas might sound incredibly lucky and extremely beautiful, but some aspects make it hard. Efforts are affected by extreme heat and humidity, summer lightning storms, and biting insects of all sizes and shapes, including those invisible to the eye but with jaws able to create minor lacerations in the skin. They can drive someone to complete madness as their bite can light the skin on fire. Hiking through swampy, poison-ridden plants carrying loads of gear deters all but the most determined person. One day of exploration produces an itchy body, sunburn, dehydration, several cuts and bruises, and additional pains that show up the next day while attempting to get out of bed.

What drives me after twenty-six years is still the emotions that exploration gives me. There is a sense of adventure and expectations; the curious mind always asks questions, and picks up new features and creatures even before arriving at the cave. When I find answers, connections, and information, I make one more step forward towards conservation.