Tech History: You’ve Come A Long Way Baby

By Michael Menduno

Depending on how you count it, technical diving quietly turned 30 years old last Fall, marked by the anniversary of Dr. Bill Stone’s Wakulla Springs Project 1987. What was once considered the radical fringe has taken its rightful place as the vanguard of sport diving. Today, nitrox is nearly ubiquitous among sport divers and helium mixes are the gas of choice for deep diving – deep air diving is no longer considered sane. Mixed gas dive computers are commonplace, and tekkies now represent the largest user group of closed circuit rebreathers on the planet, surpassing the combined militaries of the world.

The situation was very different when these technologies were just being introduced to sport diving in the late eighties and early 1990s, which I dubbed the “technical diving revolution” akin to the “PC Revolution” in the world of computing. At the time, 130 feet (40m) was considered the maximum depth limit for scuba; decompression diving was strictly verboten, and the only recognized breathing mix was air.

Organized by caver, explorer, and engineer Bill Stone, the Wakulla Springs Project was the first amateur large scale mixed gas expedition and arguably the poster child for technical diving. As such it serves as an appropriate demarcation for the birth of tech diving, though it would be another five years before this type of diving got its name.

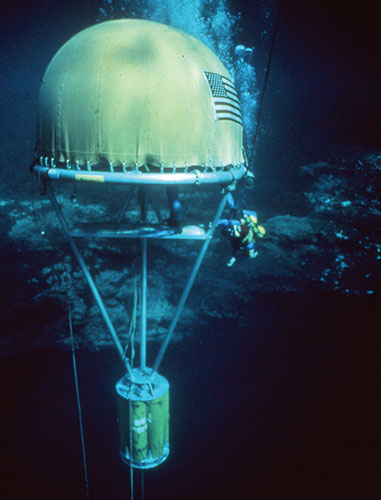

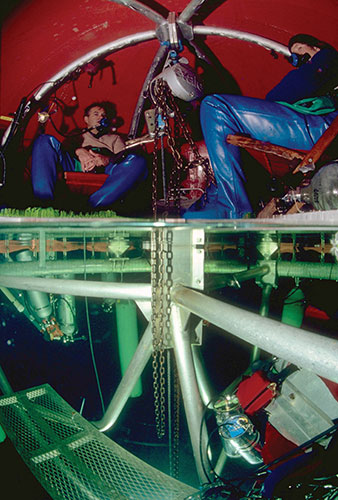

During the Fall of 1987, Stone and company (including the legendary explorer Sheck Exley and underwater filmmaker Wes Skiles, now both deceased, and veteran explorer and educator Paul Heinerth), conducted more than 80 mixed gas dives and were able to map some 2.3 miles (3.7km) of underground passageway at depths ranging from 260-320ft (79-98m). To do this they used a host of new technologies. Techniques included open circuit heliox with nitrox and oxygen for decompression, high pressure cylinders, highly-modified, long-duration scooters, and an underwater decompression habitat. Compared to sport diving at the time when few could even spell the word ‘N-I-T-R-O-X,’ Wakulla was the equivalent of an

underwater moon-shot.

Though the Wakulla Springs dives were accomplished using open-circuit scuba, Stone realized that rebreathers would eventually be needed to overcome the limitations of open circuit gas logistics for deep cave diving. Accordingly, Stone and his engineers built a 165-pound (75kg) prototype, the MK-1 fully redundant rebreather, dubbed F.R.E.D. i.e. “Failsafe Rebreather for Exploration Diving,” which Stone tested during the project by conducting a 24-hour long dive.

It was precisely this kind of geeky, data-driven, Do-It-Yourself exploration mindset, exemplified by Stone and his cohorts, that helped create technical diving and made it what it is today.