The Ice Man Mario Cyr

The first person to film polar bears from the water—meet the fish man who lives under the ice, and stores his beer there too…

Words by Jill Heinerth

Mario Cyr’s name should be known to all Canadians, from coast to coast to coast. However, our French speaking citizens do not always receive the recognition they deserve in the English speaking parts of our country. Hailing from a remote archipelago, few Canadians are even familiar with Mario’s birthplace—the Magdalen Islands, more appropriately referred to as Les Îles de la Madeleine. Part of the province of Quebec, the island group is situated right in the middle of the Gulf of St, Lawrence not too far from Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. Mi’kmaq hunters looking for walrus were the first visitors to the islands, and Jacques Cartier was the first European explorer to arrive, in 1534. Some segments of the population are descendants of survivors from over 400 shipwrecks in the area. Today, the 14,000 people that inhabit the eight islands enjoy warm 68°F (20°C) water in the summer but are beset by ice for the winter. Many citizens of the Magdalen Islands (Madelinots) fly the Acadian flag and identify as both Acadian and Québécois.

Mario has trained almost 1000 divers since 1984, but the majority of his work has involved filmmaking efforts, primarily in the Arctic. He has made over 40 trips to film in Canada’s north, many lasting weeks while camping on the sea ice. Today, Mario is an internationally renowned expedition leader and world-class cinematographer. He has contributed to over 150 films for broadcasters including National Geographic, Discovery Channel, BBC, IMAX 3D, Disney, CBC, David Suzuki, la Société Cousteau, France 2, Arte and NHK Japan. Some of the sequences that Mario has filmed have received merits such as the Palme d’or at the Festival d’Antibes 2011, and a Cesar for best film documentary in 2011.

with two cubs seems

too occupied to dive. Photo: Mario Cyr

Mario’s first exposure to diving was through the famous Canadian writer/environmentalist Farley Mowat, who spent many summers diving near his home in Bluff Beach. On one occasion, Mowat asked Mario’s father if the young boy could accompany him to assist on the boat while he went diving. Mario showed up in his red Speedo bathing suit and minded the boat while Mowat jumped overboard. The two were not able to talk much since neither knew a word of the other’s language, but Mario recalls Mowat taking underwater slates to the bottom, where he would sit in ten feet (3m) of water writing some notes or stories. It was the first time Mario ever saw a man beneath the surface, and it captivated his attention.

“After finishing his writing session, Farley lent me his mask and snorkel, it was the first time I was in direct contact with the dive. I remember having followed a plaice, as well as a crab. What a fantastic moment! I too wanted to discover the wonders of the underwater world. At the time, Farley was writing about seals and whales, and he was attempting with this underwater exercise to be in their environment. What a man! To this day, he remains one of the most outstanding and exceptional characters I’ve met.”

But Farley Mowat was not the only famous person to visit the Magdalen Islands in the summer. Mario was mesmerized by the sight of the helicopter and the Canadian army squad that accompanied another visitor; the large aircraft was attracting the interest of all the local children. It was only later that Mario learned the identity of the second diver. It was none other than Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau. Mowat and Trudeau had a deep friendship and a passion for diving. Watching the two men dive together, Mario was confident he would get his chance to dive, too.

Soon Mario saw for himself the beautiful inhabitants near his home. “Lobster, several species of crab and plaice, sculpin, mackerel, herring, four species of seals, rock gunnel, cod, ocean pout, Arctic and radiated shanny, skate, capelin, green sea urchins, sand dollars, sea squirts, sea cucumbers, brittle stars, various types of starfish, razor shells, clams, mussels, scallops, moon snails, periwinkles, several species of anemones, at least six types of algae, sponges, jellyfish, sea butterflies and more! There is a truly exceptional diversity of species in these waters. The seabed is algae green, coral pink, and various shades of grey.”

Opportunity knocks

By 1984, he was working regularly as a commercial diver. In that year, a visiting film crew hired him as an expedition guide. He knew where they could find the best opportunities to film harp seals. The cameraman in the group found the water too cold, so taught Mario how to operate the camera. After that fortuitous opportunity, he continued to shift his career into photography and cinematography.

In 1991, Mario made his first trip to the Arctic, and since that time he has accumulated more than two years in Canada’s north. Also, he has spent over 16 months in Antarctica. When I asked him why he continues to visit the polar realms, he said: “The big space, the feeling of cold, communion with nature, animals, polar bear, narwhals, walruses, belugas, whales, the light, the silence, the rhythm of life, and certainly the Inuit people that I adore, and who taught me to live and survive in hostile terrain.” Mario’s eyes light up whenever he speaks about the North. He has friends in every hamlet and is welcomed with open arms by Inuit guides, their parents, and their children. It is clear he belongs in the icy parts of our world.

When Mario reflects on the changes that he has seen since 1991, he gets a little somber. The most significant difference that he has witnessed is the diminishing pack ice. “The area decreases from year to year, which greatly impacts the animals like polar bears,” he said. But he has also noted a change in the thickness of the ice that remains. In the 1990s, “It was rare that we stopped to probe the thickness of the ice because it was sufficiently thick to travel in a snowmobile with a komatik [sled]. Today we have to stop several times a day to measure the thickness of the ice because it becomes more and more dangerous to travel on this increasingly thin ice.” He has also noticed that the location and migrations of particular mammals have changed. There used to be reliable places to find walrus or narwhals, but now they go to new sites and show up at different times. It makes it very difficult to film but also increasingly difficult for the Inuit people who still hunt and fish traditionally on the land.

Bobbing heads

Mario was the first person to film walrus and polar bears from the water. When I worked with Mario in the summer of 2018, he advised me that even after more than 100 walrus dives, he still fears them more than any other animal. As he and I geared up in a 24-foot (7m) canoe, he pointed out that the nearby walrus was bashing his tusks on the ice to show us what he might do to us if given a chance. Walrus are known to bite and crush the heads of seals. We jumped into the water together and dropped to the bottom hoping to catch a minute or two of feeding. With strict instructions to stay glued to his left side, we quickly swam around the shallow, murky water looking for some action. I had one eye in the viewfinder of my camera and one eye on Mario. He had first tried this technique in 1991 while working with Adam Ravetch. After successful filming of a walrus, they stepped up to do the same with polar bears. For me, filming the polar bears felt far more dangerous. As soon as we found a lone swimming bear, we jumped in the water with scuba gear, cameras, and a lot of weight. The bear zeroed in on our bobbing heads, swimming quickly at up to six miles per hour (10 km/h). At the last possible moment, we deflated our wings and plunged—hoping to be faster than the bear. Of course, the idea is to get the shot of the bear on the descent. It is a tall order in some of the fastest tidal currents in the world and, having attempted to get the shot myself, I have even more respect that Mario has ever caught a money shot!

When recounting some of his memorable filming experiences, Mario has trouble choosing a favourite. “The first time I did the sardine run in South Africa was pretty impressive. I ended up in a sardine ball with dolphins, cape birds, coppery sharks, white sharks, whale sharks, and whales. But I would also say one day in Naujaat (Repulse Bay) the encounter of an unexpected polar bear was quite remarkable. I had just filmed a polar bear in the water that was swimming over me. When I got the shot, I made sure that he continued his way. Rising to the surface, I felt something coming up behind me as I looked back I saw another bear that was approaching, barely six feet [2m] from me. My heart stopped beating, but I had time to take a picture of fear before I went down to the bottom. We were both surprised, but I think I was more scared than the polar bear.”

premiering fall 2019. Photo: Jean-Benoit Cyr

Beyond diving, Mario rarely stops moving. He has worked in 60 countries but still loves being home in his islands, where life is peaceful. In 2010, he decided to open Bistro Plongée Alpha that brought coffee and diving history together in one place. The walls are decorated with his photos, and his family runs the kitchen, making it feel like you are visiting the Cyr’s home. In 2017, he hooked up with a small microbrewery to create a unique beer in his image. Once brewed, Mario places the kegs and bottles on a palette that he anchors beneath the sea ice. The brew ages underwater until May when he makes another ice dive to retrieve it. The robust 8.0% beer is labeled with the message, “The story tells that Mario Cyr is a fish man who practically lives under the ice. He even has a bistro at the bottom of the sea where he makes beer in the shelter of the storms.”

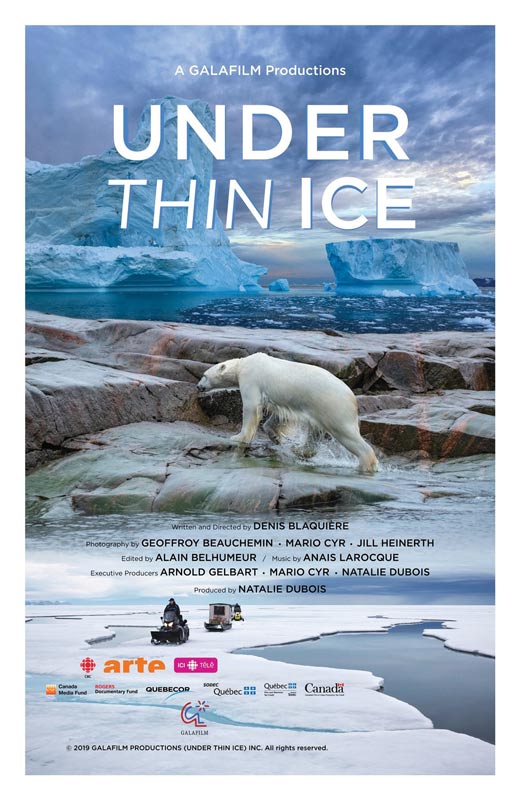

Through the summer of 2018, Mario and I worked on a feature documentary called Under Thin Ice. We tell the story of polar marine life in troubled waters. The show will air in Canada on David Suzuki’s Nature of Things and internationally on numerous other broadcast networks. Mario has also recently released an exceptional book that chronicles his experiences in the polar regions. The hardcover volume of L’Aventurier des Glaces was published in the French language in late 2018 and will soon be available in English.