A Whale of a Dive

Scientists have recently revealed the true champion of the deep

Photo: Erin A. Falcone/Cascadia Research /Collected under NOAA permit 16111

Even the whale watchers among us are impressed by the scientific revelations released recently by cetacean researchers at the Cascadia Research Collective (CRC) in Olympia, Washington. They’ve been studying Cuvier’s beaked whales over the past few years and what they’ve learned about these comparatively diminutive creatures is simply astounding.

In the wake of their study findings (published in the journal PLOS One in late March) news agencies around the world reported the facts with superlatives along the lines of, “If there were a gold medal for diving it would go to this animal.”

So, what’s up with the Cuvier beaked whale? More accurately, what’s down? Well, the record shows this whale knows its stuff. The shy, elusive, marine mammals were tracked off southern California with the help of satellite tags that transmit when the whales are at the surface, providing accurate data of the dives in between their breathing intervals. And what the researchers learned is that this unassuming creature went deeper and stayed longer than anything in the ocean, ever, that’s on the record to date.

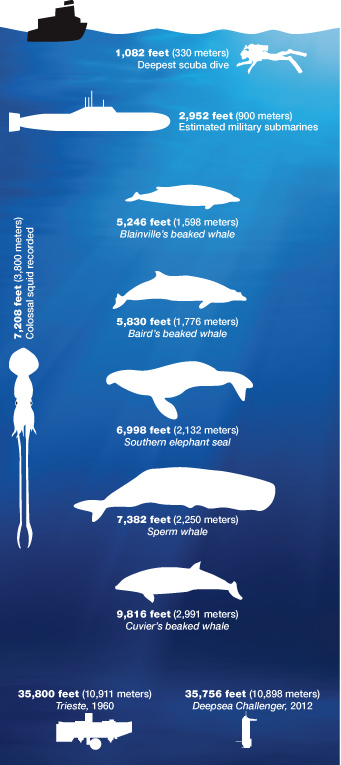

The electronic tags recorded that the whales reached depths as great as of 9,816 feet (2992m). That’s just shy of two miles or nearly three kilometres deep! And this extreme depth achievement wasn’t all. They remained underwater for as long as 138 minutes, that’s two hours and 18 minutes! And if all that doesn’t take your breath away consider that after such a mind blowing performance they’d spend as little as two minutes on the surface before diving again.

The study’s lead researcher, Greg Schorr, said that, “Taking a breath at the surface and holding it while diving to pressures over 250 times greater is an astounding feat.” Perhaps more than most, divers will appreciate the truth in this. Not that humans are any measure of this kind of ability, but the Guinness Book of World Records lists the longest breath hold by a person at 22 minutes, but even that’s qualified by breathing pure oxygen in preparation for a record achieved by floating completely still in a pool (a freediving discipline called static apnea) and certainly not diving vigorously to bone crushing depths that no human could withstand.

How do they do it?

How does the Cuvier beaked whale pull this off? In a word we can chalk it up to evolution. “This species is highly adapted to deep diving,” Schorr says. “These are social, warm-blooded mammals that have adapted to actively pursue their prey at astounding depths that are up to 2.8 kilometres away from their most basic physiological need: air.”

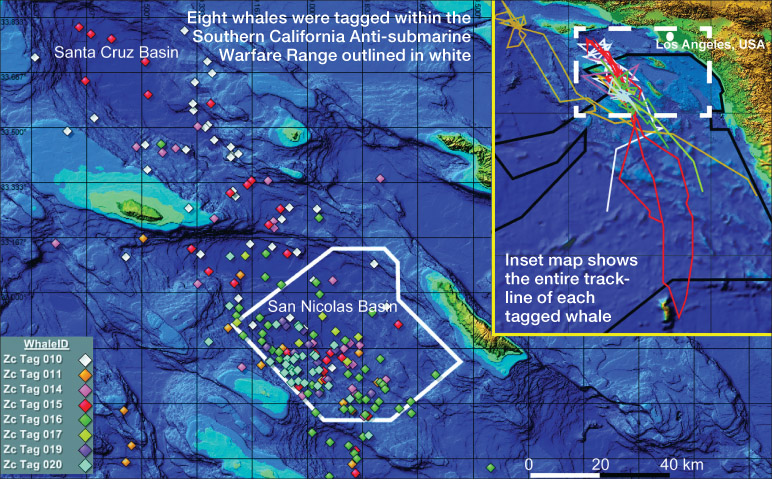

What the researchers have learned confirms what has been generally understood for some time: Cuvier’s beaked whales are expert divers. Knowing more precisely the degree of their skills and abilities has been due to a paucity of behavioural field data. Schorr and his Cascadia colleagues succeeded in attaching tags to eight whales, collecting over 3,700 hours of diving data. In a large area of the Pacific Ocean off the southern California coast the scientists tracked and monitored the animals amassing invaluable information that covered more than 1,000 individual deep dives to average depths of 4,600 feet (1,400m) and many more shallower dives, some 5,600 in all, to the lesser average depth of 900 feet (275m).

The study team observed that typical behaviour was for the whales to make a single deep foraging dive followed by a series of shallower dives, all with very short – just a few minutes – intervals between each descent. Through this close observation and data record, the science team learned of the extreme, record breaking ability of Cuvier’s beaked whales.

The animal’s impressive performance is better understood looking at the inside story. Beaked whales have very high levels of myoglobin protein, which stores oxygen in their muscle cells. Scientists have found that in whales and seals myoglobin has special ‘non-stick’ properties allowing the marine animals to pack in huge amounts of oxygen without ‘clogging up’ their muscles so that the need to breathe is less frequent even as they exert energy on deep dives.

Study researchers also say that a key adaptation giving beaked whales an edge when deep diving is that they have fewer air spaces in their bodies. This fact makes them more resistant to the crushing pressures at great depth and also likely serves to reduce the uptake of dissolved gases into their tissues, which can lead to decompression sickness.

Size Doesn’t Matter

Size Doesn’t Matter

Cuvier’s beaked, or toothed, whale is in the Ziphiidae family, comprised of 22 species that are notable for their elongated beaks, but about which not so much is known. They are moderately sized marine mammals in the range of 13 to 43 feet (4-13m) and weigh between one and 15 tonnes. Named for the French anatomist Georges Cuvier, who first described the species in 1823, they’re the most widely distributed of their family, found in tropical and temperate seas but not polar regions. They’re pelagic and favour deep water habitat. A sort of torpedo-shaped animal whose colouring ranges from grey to a red/brown to pale white, they prey on deep sea fish, which they are adept at finding.

With whales you might reasonably think that size matters where diving ability is concerned. And as a general rule, one scientist said, dive depth and duration does tend to scale with body size and mass; however, the CRC findings suggest that at the very least there are exceptions to the rule. The sperm whale is largest of the toothed whales and also dives deep for prey but typically these considerably larger animals dive to a depth of about one kilometre. Of course they can and do dive deeper than that but their performance falls short of the prowess exhibited by the Cuvier. Elephant seals are also among top deep diving mammals. They’ve been documented diving to depths in excess of 7,800 feet (2388m), about a mile and a half. And they are also prodigious breath holders with duration in the two hour range; however, the record shows such deep dives are infrequent and, Schorr says, followed by comparatively longer recovery time at the surface.