Finding Cool Corals

It’s one of my favourite British Columbia dives.

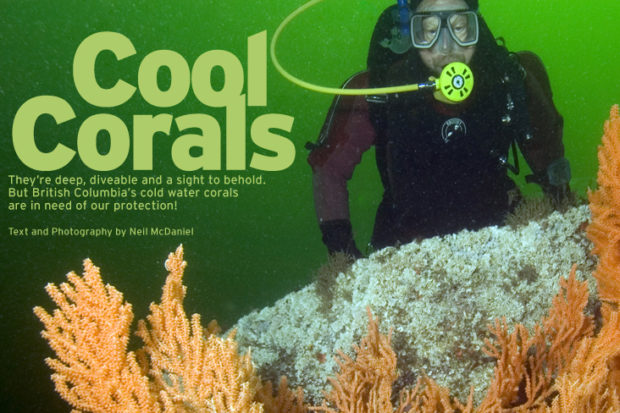

We tie up close to shore – really close in fact. The drop-off in Jervis Inlet is precipitous; a mere stone’s throw from the low-hanging trees the sounder registers depth at more than 400 feet (120m). Yet for a deep dive, it’s relatively mellow. As you drop down the vertical face you can admire the bizarrely sculpted cloud sponges along the way. It’s a relaxing free fall to 150 feet (45m), where you put on the brakes with a little air in the BC. Flick on your lights and the gorgeous fans of candelabrum coral blaze in vivid pink. A picket fence of three-foot (1m) fans crowds the edge of the rocky ridge, an eye-popping contrast with the surrounding yellow and white cloud sponges.

These lovely colonies are specimens of the gorgonian coral Paragorgia pacifica, which grows in gnarly, hand-shaped fans on deep-water ridges swept by mild to moderate tidal currents. The fans are anchored to the bedrock by a sturdy holdfast while the fan branches repeatedly from the main stem. The branches terminate in rather bulbous tips and are covered with retractable, translucent eight-tentacled polyps. If treated roughly the supple branches can be broken, so divers need to fin carefully around these fans and the cloud sponges, which are even more delicate.

Logging Hazard

When divers first discovered these gorgonians at accessible depths back in the early 1970s, there was justifiable concern that the colonies would be ravaged by those looking for a trophy to display at home. Fortunately we soon realized the folly of that, but a more insidious threat came from the logging industry practice of storing rafts of logs along shore while waiting for a tow to the mills. As the logs bumped about in the booms, bark, branches and other debris broke loose and rained down the slope, smashing and smothering both gorgonians and sponges. Concerned divers alerted regulatory agencies to this problem and pressed for ecological reserve status for a small stretch of Agamemnon Channel. That official status was never attained but at least the gorgonians got onto the radar of other users of the waterway. Unfortunately, the result was not so positive for another area within the channel that was converted into a log storage pond. Some of the shallowest fans of pink candelabrum coral I had ever seen (in as little as 110 feet (34m) of water) were completely destroyed by the relentless blizzard of wood debris from above.

While Paragorgia pacifica is widely distributed along the BC coast and into Alaska, it is only rarely situated at depths shallow enough, let’s say within 150 feet (45m), to be observed by divers. Of course technical diving, with its greatly increased depth range, has potentially changed all that. Yet even so there are currently only two known areas on the BC coast, Jervis Inlet and Tahsis Narrows, where these beautiful gorgonians are accessible to divers.

Travelling Boulders

Back in the early 1980s researchers probing the depths of Knight Inlet on the central BC coast with the submersible Pisces IV encountered large fans of red tree coral on its glacial sill. Boulders of various sizes were found scattered over the sill, many of which were colonized by impressive fans of red tree coral. The very fact that this coral was present was interesting, but the scientists discovered something else extremely curious. They noticed that behind some of the boulders were long drag marks, evidence that when the coral fan on a particular boulder became big enough it acted like a sail in the strong tidal currents that flow over the sill. This caused the boulder to be gradually transported until it was removed from the influence of the current or until the fan caused the boulder to tip over, thus spilling the “wind” from the sail created by the fan.

Former Port McNeill teacher and dive instructor Ralph Delisle, after speaking with the Pisces pilots, dived the sill with Dave Wardell in 1982, finding coral fans at 100 feet (30m). Ralph took some pictures, but at the time did not realize the significance of his remarkable find. Meanwhile, I bumbled along for years with the belief that Primnoa pacifica was found only far below diving depths. That changed in an instant when Ralph e-mailed me his pictures – more than 20 years later. Immediately, I recognized them as red tree coral. That got me stoked! In over 40 years of BC diving I’d seen this elusive species just once, and that may well have been a broken branch snagged by a fishing line and dropped in shallow water.

In June 2008 I finally had the chance to get up to Knight Inlet for a look-see. Knight Inlet is a monster of a fjord, more than 50 miles (80km) from mouth to head. It took over two hours in Steve Lacasse’s (Sunfun Divers) speedy dive boat to reach the site from Port McNeill. Doug DeProy and I jumped in and swam for what seemed like forever against an unrelenting current over a sloping, featureless pebble and cobble bottom, seeing absolutely nothing in the way of coral or anything else. Finally, getting low on air and BT we saw a huge boulder looming ahead. Closer in we could see it was bristling with red tree coral fans, the biggest about three feet (1m) across. With little time for more than a high-five and a few quick photos, we headed to the surface extremely happy campers.

The next day we explored the site again, this time heading further west, hoping to find the boulder field observed by the Pisces submariners. Andy Lamb and I beat our way west against the flooding current, eventually encountering some scattered boulders with small fans attached. We could see that in some cases the fans were oddly bent, evidence that they had tipped their host boulders over and were now growing vertically to capture the plankton-rich currents sweeping over the reef. As Andy and I followed the boulder field inshore, both the size of the rocks and the coral fans increased, with some of the biggest fans up to four feet (1.2m) across. We found coral fans all the way up to a depth of 50 feet (15m), which seemed quite extraordinary for what I had considered a ‘deep-water’ gorgonian. Most of the fans that we observed were uniformly an orange-pink colour with very wiry, tough and dense branches. In dead specimens the densely calcified, dark brown internal stem could be seen.

Wide Range

Primnoa pacifica has been found in even shallower water in Glacier Bay and Holkham Bay, Alaska. In 2003 these gorgonians were observed during scuba surveys as shallow as 30 feet (9m) deep. Researchers suggested that low temperature, stable salinity and low ambient light levels encouraged Primnoa to colonize the rocky drop-offs. And because there is an accurate record of the deglaciation of Glacier Bay, they were also able to estimate the growth rates for these corals at 0.9 inches (2.4cm) per year, an important figure to know when trying to determine the time it might take for damaged corals to recover.

Primnoa pacifica ranges from the Sea of Japan westward across the Aleutian archipelago and south to La Jolla, California, generally at depths of 210 to 2,625 feet (64 to 800m). Off the BC coast, it appears to be widespread and reaches considerable size, with the biggest fans reaching more than eight feet (2.4m) tall. In very large specimens the main stem can reportedly be more than 2.4 inches (6cm) in diameter and cross-sections reveal growth rings much like a tree. Despite its strong holdfast and wiry, flexible branches, Primnoa beds are often seriously damaged by bottom trawling and other bottom fishing methods such as long-lining and trapping. Primnoa is easily the largest coral found off the Pacific coast—in the Gulf of Alaska a gigantic specimen 23 feet (7m) tall has been observed during a submersible dive. I’ve seen some enormous gorgonian fans on tropical Pacific drop-offs that would rival this size, but not many.

Discovery At Port Hardy

In the early 1980s Larry Mangotich and Gary Mallender began exploring the islands and reefs off Port Hardy, as they scouted new dive sites for their live-aboard charter business aboard the Oceaner. At the south end of the Gordon Group they discovered densely packed coral fans thriving in the strong currents sweeping through Queen Charlotte Strait. These corals turned out to be the pink gorgonian, Calcigorgia spiculifera, never before observed by divers.

As they explored more sites they found that this pink to buff colour, wiry gorgonian was actually quite abundant here and north along the central BC coast and into the passages of southeast Alaska.

Interestingly, this coral often provides a convenient elevated perch for the basket star Gorgonocephalus eucnemis and it’s not uncommon to observe fans with dozens of juvenile basket stars clinging to their branches.

Deep Coral Needs Protection Now

The gorgonian corals (Order Gorgonacea) are just one group of cold-water corals found off Canada’s west coast. This broad category also includes hydrocorals (Order Anthoathecatae), black corals (Order Antipatharia), sea pens (Order Pennatulacea), cup corals (Order Scleractinia) and soft corals (Order Alcyonaria)—a total of 61 species by most recent counts. About a third of these creatures can be observed by divers while the balance are found in deeper water, down to 20,000 feet (6,100m) in some cases, although the majority of species are found between 600 and 6,000 feet (183 and 1,830m) on the continental shelf. In Alaska, which has more than 34,200 miles (55,000km) of coastline, 70 per cent of the US continental slope and plenty of deep, really cold water, the number of corals is much higher—141 species at last count.

Cold-water corals, especially the gorgonians, often dominate deep-water habitats, forming complex thickets that create important refuges for deep-water fishes and mobile invertebrates. Their large size and vertical orientation create deep-water habitat with three-dimensional complexity, creating shelter for other marine life, protection from strong currents and predators, and feeding and spawning areas. Unfortunately, these fields of corals are threatened by a commercial fishing method known as bottom trawling or dragging in which a pair of massive steel trawl doors connected by heavy chain and fitted to a mesh net are towed over the sea bed like a gigantic scoop, smashing corals and sponges and swallowing everything in their path.

Collateral Damage

While the targeted and economically important species include deep-water flatfishes, hake and pollock, the indiscriminate and brutally clumsy nature of this fishing method causes extensive collateral damage. It is estimated that bottom trawling has already destroyed 50 per cent of the continental shelf coral gardens off British Columbia, despite Fisheries closures that ban trawling in specific areas. Between 1996 and 2002 fisheries observers in BC waters reported that more than 90,000 pounds (41,000kg) of corals and 160,000 pounds (72,600kg) of sponges were ripped from the seafloor and discarded, innocuously described in reports as ‘by-catch’. In Alaskan waters the situation is far worse: between 1997 and 1999 the National Marine Fisheries Service estimated that one million pounds (454,000kg) of corals and sponges were destroyed in the Bering Sea and Aleutian archipelago, 90 per cent due to bottom trawling.

If fishers were allowed to drag huge, heavy trawl nets over the Great Barrier Reef in order to catch a few marketable fish, trashing 200-year-old staghorn and elkhorn corals, environmentalists would go crazy. But because the devastation caused by this fishery occurs unseen hundreds or thousands of feet below the surface of the sea, few of us even know it is happening. Deep-water surveys to map the distribution of these precious coral beds and ban destructive bottom fishing there should be a top priority, but given the huge area of seabed off Canada’s west coast, it’s a daunting task.

Ancient Gorgonians

Some gorgonian corals reach astounding ages, and rank among the oldest living creatures on our planet. Using submersible vehicles, researchers from Texas A&M University have recently discovered beds of Leiopathes sp. at 1,200 feet (366m) off the coast of Hawaii that were carbon dated at 4,265 years old. Our large gorgonians, such as Paragorgia, Primnoa and Calcigorgia are apparently nowhere near as ancient, although six foot (2m) specimens of the red tree coral have been aged at over 120 years.

The complexity and significance of the deep-water corals of our oceans are only beginning to be understood. Modern technology, including deep-diving submersibles and remotely operated vehicles, have transported us ever deeper into the vast unexplored reaches. In British Columbia and Alaska scuba divers are lucky enough to be able to catch a glimpse of some of these impressive cold-water corals in shallow water, but we cannot continue to ignore the destruction caused by anachronistic fishing practices. Cold water corals are indeed cool, and if you want to help conserve them, get informed and hound your fisheries managers until they acknowledge the problem—and do something constructive to fix it.