Code name: Habbakuk – ‘Most Secret’

Text by Susan R. Eaton

The Allies had a plan to crush Nazi aggression using gigantic iceberg aircraft carriers built in Canada’s north. Code named Habbakuk, the scheme was eventually torpedoed and the prototype vessel sank in a remote Rocky Mountain lake.

Most shipwrecks are frozen in time, but the Habbakuk, the 1:50 scale prototype of a 1,970-foot long (600m) aircraft carrier constructed largely out of ice, simply melted and slipped below the surface of Patricia Lake in Alberta’s Jasper National Park, guarded all around by Canada’s Rocky Mountains.

Constructed by conscientious objectors during the winter of 1943 — and disguised to resemble a large boat house on Patricia Lake — the iceberg ship was heralded by Sir Winston Churchill, Prime Minister of Great Britain, and Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, Chief of Combined Operations in Great Britain, as the Allied Powers’ top secret weapon against German U-Boats that were attacking naval convoys in the North Atlantic.

One of the weirdest inventions of modern wartime, Churchill planned to launch the invasion of Europe from a fleet of iceberg aircraft carriers. He also envisioned using bergships, as floating islands and refuelling stations in the Pacific Ocean, to deploy fighter aircraft and B-29 bombers against the Japanese Forces.

Desperate times required desperate measures, and out-of-the-box thinking was needed to win the war.

Pyke’s Proposal

Geoffrey Pyke, an eccentric British scientist with a history of mental instability that landed him in an American insane asylum, developed the concept of an indestructible iceberg ship. After the Titanic hit an iceberg and sank in 1912, scientists tried to destroy icebergs in the North Atlantic, using dynamite and torpedoes. But, the icebergs held fast, due to the inherent strength and buoyancy of ice. Pyke initially recommended towing icebergs south, from Greenland, and carving airstrips on top of them — quickly concluding that this plan was logistically impossible, Pyke reverted to plan “B” or using ice as an indestructible construction material. He named the bergship the Habbakuk, after a prophet in the Old Testament, misspelling her name in the process.

The full-scale iceberg aircraft carrier was to be plumbed inside like a refrigerator — it would be made of 280,000 blocks of ice, and the hull would be impenetrable to U-boat torpedoes. Made of ‘pykrete’ (Pyke plus concrete), it was a slurry of water and wood pulp that proved extraordinarily strong when frozen. The Habbakuk would carry 200 aircraft, house 2,000 men in metal containers, and would weigh two million tonnes. In contrast, the RMS Queen Mary, a Cunard-White Star liner and one of the largest ships of the day, weighed in at 91,000 tons. The Habbakuk came with a $100M price tag to boot.

The prototype, measuring 60 feet (18.3m) long, 30 feet (9.2m) wide and 20 feet (15.9m) high, was built in remote Jasper National Park — where the winters were cold and ice abundant — under the watchful eye of the Canadian military and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

Pyke’s weird and wacky idea worked. A fleet of bergships was to be built in Corner Brook, Newfoundland, and would require a staggering workforce of 35,000 men. But, much to Churchill’s dismay, the Canadian government couldn’t manufacture full-scale iceberg aircraft carriers for another two years. Given the staggering price tag and the fact that the Battle of the Atlantic had turned in the Allies favour, Project Habbakuk was scrapped.

Even today, the story of Habbakuk remains a mystery, and only a select few Canadian divers know of the extreme wartime efforts that took place in Jasper National Park.

Doctoral Dissertation

Dr. Susan Langley, the state underwater archaeologist for Maryland, learned of the bergship’s existence during the early 1980s when she was studying archaeology at the University of Calgary. Intrigued by the farfetched tale of an iceberg aircraft carrier, Langley combined her love of scuba diving with underwater archaeological studies into a Ph.D. dissertation on the Habbakuk.

The construction of the Habbakuk, she said, involved a jacket system engineered by Ottawa’s National Research Council. “Think of a shoebox, and then put a smaller shoe box inside — and that’s the Habbakuk,” explained Langley who has logged two dozen dives on the wreck.

The Habbakuk’s walls and floor were constructed of wood. And, the wall cavity and the spaces between the floor joists were filled with an insulating mixture of asphalt and charcoal. An air-cooling system delivered cold air to the central refrigeration chamber and to the asphalt-insulated pipes running between the floor joists and up the four external walls.

Ice blocks were cut from the lake — pykrete wasn’t used in the 1:50 scale model — and stacked over the floor pipes. In turn, the refrigeration unit was installed on top of the ice blocks, and the central chamber was padded with more ice, slush and water, creating a big iceberg sandwich. In July 1943, thermocouples embedded in the prototype measured a core temperature of 14°F (-10°C) and external wall temperatures of between 21.2°F (-6°C) and 15.8°F (-9°C).

“Don’t let the truth get in the way of a good story,” said Langley, tongue in cheek. She cautions divers against harbouring grandiose expectations of the iceberg aircraft carrier that, she said, looked more like Noah’s Ark under construction. “I can’t make it sexy for divers; they have to love the Habbakuk for itself.”

Added Langley: “It’s a very cool piece of Canadian wartime history — you have to visit the Habbakuk with the intent of touching (figuratively) the past.”

Bergship on the Bottom

Experiments concluded at the end of August 1943, and the Habbakuk’s roof and central refrigeration unit were removed. The ice melted a few months later, sending the bergship to the bottom of Lake Patricia.

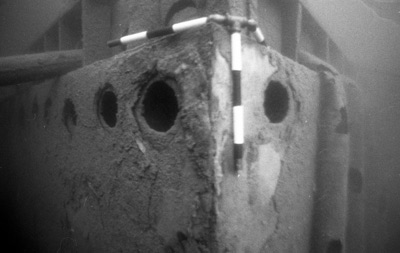

The wreck of the Habbakuk includes the refrigeration pipes, one standing wall and a jumble of equipment lying diagonally on a 30-degree slope, in 40 to 130 feet (12-40m) of water. Water temperatures vary from 54°F (12°C) on the surface to 37°F (3°C) at 100 feet (30m), and dry suit-clad divers must account for diving at 4,200 feet (1,280m) of altitude.

Today, the Habbakuk receives about twenty visitors a year, intrepid divers who paddle 30 minutes across the lake, in gear laden canoes, or hike almost a mile (1.5km) along a horse trail to the poorly marked dive site. Divers hunt for a cross nailed to a tree, a rusted metal tether ring on the shore, and telltale signs of asphalt on the shore and trailing into the water.

Divers can also reach the Habbakuk via a 15-minute scooter ride or a 45-minute underwater swim, finning at a depth of about 20 feet (6m). While Parks Canada prohibits motorized boats on Patricia Lake, small electric trolling motors are allowed.

For Cathie McQuaig, the executive director of the Alberta Underwater Council, part of the Habbakuk’s allure is its remote location and logistically challenging access. “Diving in Alberta is not without its challenges,” explained McCuaig, “but it has its rewards as well.”

The Alberta Underwater Council represents 3,000 divers, yet very few have visited the Habbakuk. According to McQuaig, she and her husband, John McQuaig, a technical diving instructor, are among the “elite few to dive the Habbakuk.”

The McQuaigs have visited the wreck about a dozen times. In order to avoid algal blooms in the summer, they’ve even applied for ice diving permits from Parks Canada. Because the ban of motorized vehicles on Patricia Lake extends to the winter months and to snowmobiles, the couple has dragged dive gear across the ice in toboggans. And, they’ve replaced motor oil with environmentally friendly canola oil in their chainsaws.

High Dive Biz

Nathan D’Heer, owner of Jasper Dive Adventures, grew up on the shores of Lake Patricia where his family owns and runs the Patricia Lake Bungalows, a collection of both rustic and luxurious cottages in the shadow of Pyramid Mountain. At age 22, D’Heer has logged 32 dives on the Habbakuk.

The Patricia Lake Bungalows rents kayaks, rowboats and canoes to tourists and divers alike. D’Heer launches boats from a private floating dock, cutting down on travel time to the Habbakuk. Visiting divers often receive permission, from the D’Heers, to launch their boats from their private dock.

D’Heer received his PADI open water certification at age 14, and worked as a PADI dive instructor in the Cayman Islands before returning to Jasper. In 2011, he opened Jasper Dive Adventures, the first dive instruction company to be located in Jasper National Park.

During his first season of dive operations — from mid-April to September of 2011 — D’Heer had 26 customers, many of whom he qualified to dive dry suits. He also certified nine open water divers, four advanced divers and two rescue divers. D’Heer and his students are often treated to iconic Canadian wildlife sightings — moose, elk and black bear — as they paddle to the wreck. On one occasion a scuba course was interrupted by a moose and her calves swimming across the lake. Mama moose likely saw it the other way around. Divers can often see schools of large trout (rainbow, lake and brook) hovering under the wreck.

It’s a ten-minute drive from Patricia Lake to the local Fire Hall in Jasper — a sleepy town of 5,000 residents — where D’Heer refills his tanks, donating the filling fees to the local fire hall charity. Stocked with a selection of new wet suits, dry suits, regulators and tanks, he has enough equipment to dress a group of six divers. “I can handle all sizes, except for seven-foot-tall people,” said D’Heer who is studying hospitality management at NAIT, the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology.

Proud to have a top secret WWII war artefact on his doorstep, D’Heer escorts visitors from all over the world on guided tours of the Habbakuk. Prior to each tour, he provides divers with the bergship’s colourful history, outlines local dive hazards and reviews the physiological effects of cold water diving.

An ‘Unexpected Surprise’

During the summer of 2011, Australians Jen Buchanan and Michelle Rossetto visited Canada’s Rocky Mountains for the first time. They discovered D’Heer’s diving brochure at a tourist information booth, and the improbable story of the Habbakuk captivated their imaginations. When faced with the choice of going mountain biking or diving the iceberg aircraft carrier, there was no contest for these adventurous divers.

“We could go mountain biking anywhere in the world,” explained Rossetto, a trauma nurse with the National Guard in Saudi Arabia, “but you can’t dive a WW II wreck in a lake in Canada’s Rocky Mountains.”

Used to the azure tropical waters of the Red Sea, the women had never experienced cold water diving — or wearing dry suits, hoods and gloves. Getting into the gear, they said, was an “exhausting” exercise, especially on a sunny, 77°F (25°C) day. “And, just when you think you’re exhausted,” said Rossetto, “Nathan tells you that you’ve got to paddle a third of a mile (0.5km) to the wreck.” Novice paddlers, Buchanan and Rossetto “zigzagged down the lake,” cutting a circuitous swath in their boat piled high with dive gear.

“It was ridiculously difficult getting in and out of the water, especially on the rocky beach,” said Rossetto who was equipped with 44 pounds (20kg) of weight.

“We were absolutely blown away by the once-in-a-lifetime experience,” added Rossetto. Getting certified in a dry suit, she said, was a completely “unexpected surprise,” as was diving in the 37°F (3°C) water that numbed their faces and finger tips. Visibility was, at best, a few metres, and was impaired by the first-time dry suit divers who hit the bottom, stirring up whirlpools of fine ‘rock flour’.

Rossetto described how she and Buchanan struggled to achieve neutral buoyancy in their dry suits. “I remember saying to myself,” ‘Jen, don’t touch that wall’”. She added: “We didn’t want to be the ones to knock down the Habbakuk’s last standing wall.”

But, the pluses far outweighed the negatives. Diving the world’s first iceberg aircraft carrier, they said, was the highlight of their trip through the Canadian Rockies.

Protecting the Habbakuk

On July 31, 1988, Langley was involved in a special dedication to the Project Habbakuk, assisting with the Alberta Underwater Archaeology Society’s installation of a concrete cairn and bronze plaque, in 40 feet (12m) of water near the Habbakuk.

Langley’s last dive on the bergship was in 2005, and she was shocked by the degree of its deterioration, including the collapse of the refrigerator unit. On the flip side, she said, the deterioration exposed previously unseen parts of the Habakkuk, uncovering more of its spiderlike web of refrigeration pipes.

Langley noted that the deteriorating wreck isn’t just nature taking its course. “The amount of graffiti and vandalism was disturbing,” she said, citing the message on the Habbakuk’s underwater cairn, “please respect our underwater heritage.”

According to McQuaig, the Alberta Underwater Council is actively educating divers to refrain from defacing underwater archaeological sites in Jasper, Banff and Waterton national parks. “I don’t know why people have to put their names on things,” she said. “Scuba divers are usually so environmentally conscious, and they need to resist any temptation, leaving Alberta’s underwater heritage sites intact.”

“Time has taken its toll on the Habbakuk,” echoed D’Heer. “I make it extremely clear that we need to respect the wreck, so that future divers can enjoy it.” D’Heer and his family are uniquely situated — as de facto onsite custodians — to conserve this unique chapter of Canada’s wartime history, playing a key role through education and awareness.

Susan R. Eaton is a geologist, geophysicist and journalist who lives in Calgary, Alberta. A diver of 32 years, she’s recently become an extreme snorkeler with a focus on the planet’s polar regions. Susan can be reached at www.susanreaton.com