Hannes Keller Diving pioneer and Renaissance man

Text by Hillary Hauser

Fifty years ago December a 1,020-foot (311m) dive off Catalina Island, California, changed everything. Hannes Keller’s revolutionary accomplishment accelerated a new age of deep sea diving, but the daring exploration came at a price

On his sixtieth birthday Hannes Keller flew a Russian MIG fighter jet, the experience an imaginative gift from his wife Esther who knows well her husband’s love of risk. A Swiss national, mathematician, philosopher, pianist, art lover, computer whizz, Keller is the quintessential Renaissance man whose 1962 deep diving achievement took place long before others had even thought of the possibility, and until 1975 he remained the only person on the planet to have touched the ocean floor at such an extreme depth.

Today, divers are able to work in deep water thanks in large measure to Keller’s s early diving experiments. The Swiss adventurer’s revolutionary dive to 1,020 feet (311m) off Catalina Island, California on December 3, 1962, was years before its time and everyone wanted to know how he’d done it. This was not a stunt as some claimed. It was a complex, scientific experiment to get man onto the deep ocean floor.

And what made Keller do it? The dive was filled with terrible risks. No one knew for certain what would happen. It seemed impossible. It would likely be the death of him. It did kill his diving partner and one of his safety divers. But Keller survived, emerging from the diving bell victorious, and though the loss of life was sobering, the result was proof that a human being could get to 1,000 feet (305m).

I first met Keller in 1968, when my husband Dick Anderson, a surviving safety diver on the 1,000-foot (305m) dive, was awarded a contract from a major American publisher to write a book about the life of Hannes Keller. We interviewed Hannes, his friends and associates. We talked to Albert Buhlmann, the scientist who worked with Keller on the procedures and gas formulas for the deep dives from his ‘lungenfunktion’ (pulmonary) laboratory at the University of Zurich. We spoke with Jacques Piccard in Lausanne. We talked to people everywhere, and little by little we

pieced together a story.

$1 Diving Bell

In 1959, someone told Hannes about scuba diving, and that was all it took. He built his own breathing device out of wood, which, in his words “Worked very bad.” Almost immediately after that he decided to work on diving problems. He approached Dr. Buhlmann with some of his ideas. A physiologist, Buhlmann had been working on the problems of pressure on the human body.

The two started working on the problem of nitrogen narcosis, its role in the ‘bends’ and as an obstacle to clear thinking at depth. Decompression also came under their scrutiny. In those days it was almost always impractical or even impossible. George Bond’s “saturation” diving techniques had not been thought of at that time.

Keller and Buhlmann had a theory that nitrogen narcosis might not be caused by nitrogen at all. With this in mind they cooked up a plan for a 400-foot (122m) dive wherein Keller would breathe a mixture of 95 percent nitrogen and 5 percent oxygen.

This dive was staged November 1959 in Lake Zurich. Using a 50-gallon oil drum that cost $1, for their diving bell, Keller went to the bottom breathing the nitrogen mix from inside the drum, which had been weighted with stones. To get back to the surface all he had to do was cut the stones off with a knife. While everyone on the surface gloried in this ‘giant leap for diver kind’, Keller was 400 feet (122m) down in the lake struggling to cut the weights off his makeshift diving bell. The discomforts became insignificant when, eventually, he emerged victorious.

There is barely enough ‘air’ to breathe and it is bitter cold, even colder than the ice water in which we now hover

Secret Tables

A major test for the Keller/Buhlmann team was to get a diver down and back in a short time. In 1956 there had been a world record dive to 600 feet (183m), by a George Wookey of the Royal Navy, but that dive had required 12 hours of decompression. Keller and Buhlmann got to work on their next project: to hit 700 feet (214m) and surface within an hour.

Working with a computer at the IBM Centre in Zurich, the two developed 400 secret tables involving gas mixtures for use to various depths up to 1,312 feet (400m). After testing these calculations on himself in high-pressure laboratory tanks in Toulon and Washington, D.C., Keller was ready for a 700-foot (214m) dive.

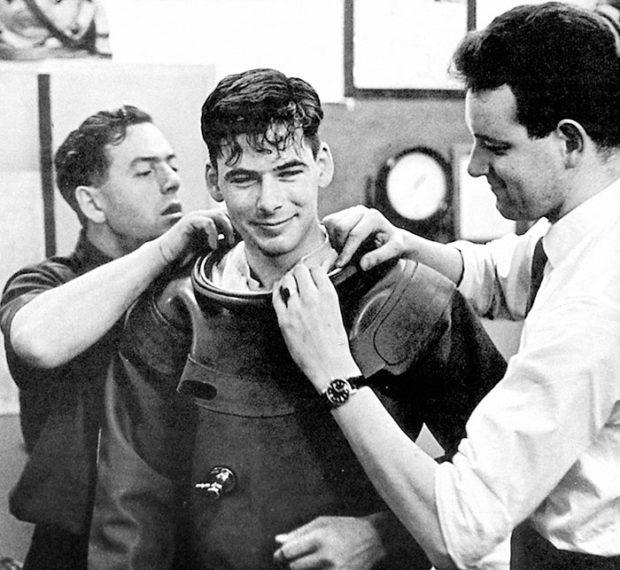

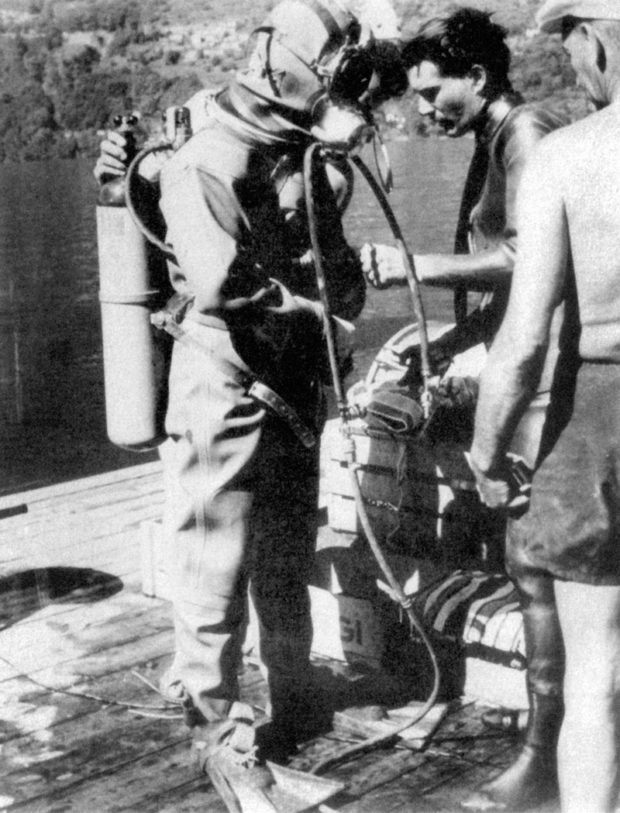

It took place on June 28, 1961, in Lake Maggiore between Switzerland and Italy. Keller’s diving companion was Ken MacLeish of Life Magazine, who was there for the adventure and to write a story. With a floating aramada of spectators surrounding a giant diving platform anchored just off the lakefront town of Brissago, Keller and MacLeish were lowered on a diving stage. Wearing dry suits and rubber helmets with faceplates and mouthpieces built in, the two divers breathed a combination of gases supplied from tall tanks lashed vertically to the frame of their diving stage.

They were to start and finish the dive with pure oxygen. Below 50 feet (15m) they would breathe three different mixtures containing some oxygen, which would be greatly reduced for the deepest part of the dive. According to MacLeish’s Life Magazine account, Keller guaranteed that neither of them would suffer nitrogen narcosis.

The divers started their descent. At 30 feet (9m), they switched from oxygen to the first gas. Then at 164 feet (50m) another change, and again at 180 feet (55m). Each time Keller made the switch for them both and then disconnected the drop lines that had supplied the previous gas.

At 328 feet (100m) the divers stopped to switch to the deep-water mixture. MacLeish later wrote: “This time the change is extreme. There is barely enough ‘air’ to breathe and it is bitter cold, even colder than the ice water in which we now hover. My teeth itch. I try to say okay but cannot manage it. Still, it appears that we can live on what we are getting.”

The descent continued: 492 feet (150m)… 525 feet (160m)… 558 feet (170m)… 591 feet (180m)… 689 feet (210m)… 705 feet (215m)… 728 feet (222m), in 7 minutes 30 seconds.

On the way up the divers stopped at 160 feet (49m) to switch gases. Over their earphones they now heard music, piped down from the surface to give them something to decompress by. At 50 feet (15m) MacLeish noticed blood and foam in Keller’s mask: an ear squeeze. At 30 feet (9m) they switched to oxygen, sitting on the stage for a time before they began exercising and kicking in place just to stay warm.

One hour after they had begun the dive, the men resurfaced: official depth 728 feet (222m). MacLeish’s story hit the August 4, 1961 issue of Life Magazine, featuring John F. Kennedy on the cover with his quote, “Any dangerous sport is tenable if brave men will make it so.”

Big Oil Interested

Now, international oil companies became greatly interested in Keller’s experiments, for in the greater depths of the world’s oceans were vast treasures of oil waiting to be tapped. No matter how sophisticated robotic arms and manipulators might become, the human hand was, and remains, the most important instrument for delicate situations, such as the workings of valves and flanges.

Shell Oil leaped at the chance to finance Keller’s next dive – the big one to 1,000 feet (305m). Out of it, the company would receive Keller’s secret technology and thereby become an instant frontrunner in offshore oil exploration.

Keller and Buhlmann extended their computerized formula of gases and they chose the Catalina Island site off Southern California, where the ocean floor drops precipitously from the shoreline into a deep ocean trench. On this occasion Keller’s diving partner was the British photojournalist Peter Small, a cofounder of the British Sub Aqua Club. Their vehicle was the diving bell Atlantis, which would be lowered from a surface support ship that carried a technical team to monitor gases and maintain contact with the divers by a surface to bell phone link. Dick Anderson and Chris Whittaker formed the safety diver team on board. In retrospect no one could figure out why there were only two safety divers, but hindsight is always sharp when a disaster occurs.

On December 3, 1962, the dive commenced. Keller and Small got into the Atlantis and the hatch was closed. The chamber was hoisted over the side of the support ship and began its rapid plunge to the bottom, stopping at various stages for the switching of gases as had been done during the Lake Maggiore dive. At 12:35 p.m. the divers reached the bottom.

As planned, the divers switched from the gas mixture inside the bell to another gas mixture supplied to them through hoses attached to their faceplates. Keller opened the hatch of the Atlantis and the two went out briefly, just long enough to plant a flag of victory on the ocean floor, and then they returned to the bell.

Fatal Errors

Once inside, the divers were to open their faceplates to again breath that gas mixture in the bell and as I recall Keller telling the story back then, he said the divers knew they would lose consciousness when they opened their faceplates, but also knew they would regain consciousness as the bell ascended.

Keller opened his faceplate and passed out. Small saw this and apparently froze, failing to open his. The bell began its ascent to the surface but was stopped at 200 feet (61m) because the surface support team noticed that the chamber was not pressurizing. There was a leak that would subject both divers to severe bends or air embolism if the ascent continued.

Safety divers Anderson and Whittaker were called into action, to go down and look for leaks. Anderson checked everything but found nothing. They came back to the surface to report. Al Tillman, who was on the support team, told Anderson that the bell continued to leak. At this point it was noticed that Whittaker had inflated his life vest and had blood in his mask. He was ordered out of the water. Anderson, meanwhile, prepared

to dive again.

Instead of leaving the water, Whittaker took his diving knife, slashed his vest to deflate it, and dived with Anderson back to the bell. This time, Anderson closely inspected the bottom hatch of the Atlantis where he discovered a small trail of bubbles escaping and the reason for it: the tip of a swim fin was visible and just enough to prevent a proper hatch seal. He motioned to Whittaker for his knife and used the blade to push the obstruction clear of the seal. The hatch closed completely, but the seal continued to leak so Anderson pulled down on the hatch and motioned for Whittaker to surface and signal for the chamber ascent to continue. He planned to ascend with the bell ensuring the hatch remained sealed.

Whittaker signalled that he understood and began his swim to the surface. Anderson waited and waited, his (early) decompression meter entering the red zone. Finally, he had to leave.

The minute he surfaced, a crewman asked, “Where’s Chris?”

Whittaker was never seen again.

Meanwhile, the Atlantis leak stopped due to inside/outside pressure differential shifts. The chamber continued on its way to the surface, and Keller regained consciousness. Seeing that Small had not opened his faceplate, Keller did so and began an intensive resuscitation attempt on the unconscious diver. But Small was dead by the time they got to the surface. Keller suffered no ill effects.

The dive was a paradox. A man had descended to 1,000 feet (305m) successfully, proving that the mysterious mixture of gases had worked, but two men had died. No one knew whether to cheer or cry. Some press reports referred to Keller as Hannes Killer, while others denounced him for not sharing his secret gases and dive formula with the scientific community. But soon after the dive Buhlmann had published the details of Keller’s dive, although few people had read that highly technical report; scientific papers tend to circulate only among scientists who know where to find them.

The diving community ignored everything and called Keller a hero. So did the Swiss.

The book on Keller was never finished because Dick felt he could not sort out the facts of the dive without question.

Some people may not understand a mind that entertains this kind of risk, though most would agree it takes a person of extraordinary will to live life to the fullest, risking failure and even death. Keller told me once, “I want to have an interesting life, that’s what I want. I am the man looking for the right mix of all things to get me into the depth of life… so at the end I can say it was worthwhile.”

Leave a Comment