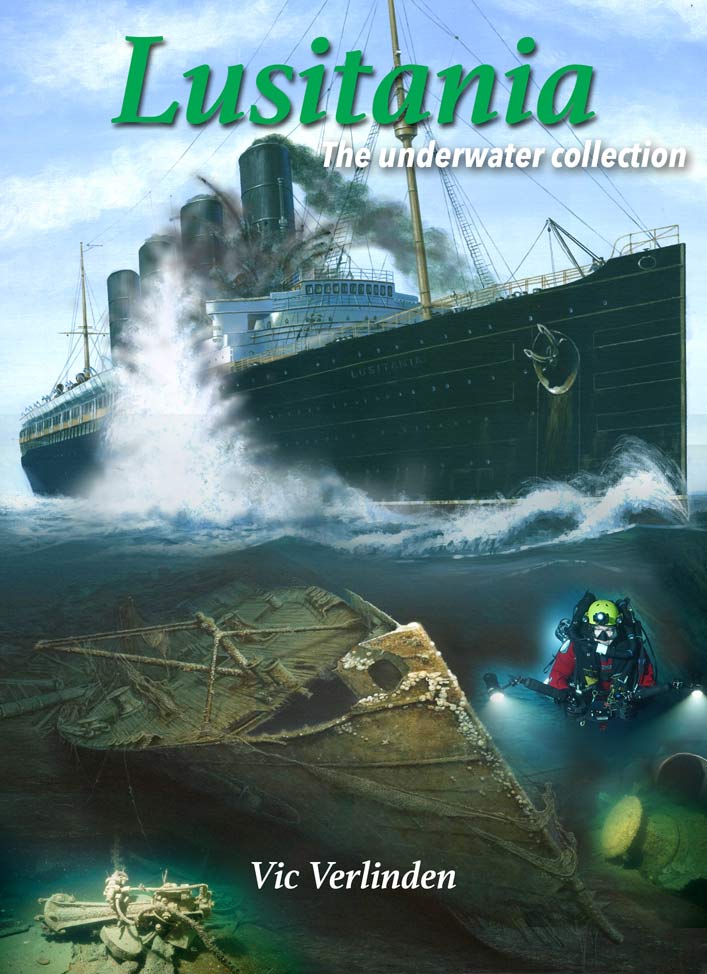

Lusitania: The Underwater Collection

Words by Vic Verlinden

Words by Vic Verlinden

Despite bad weather, entanglement hazards, and a deteriorating subject (not to mention a pandemic), a dedicated team continues to document this historically important wreck off the Irish coast. A new book of photos gives a fresh, never-before seen picture of the wreck.

When I contacted Peter McCamley in 2017 to dive on the wreck of the Lusitania, I never imagined that this would become my most important project ever.

In 2017, the project was launched to extensively document the wreck of this legendary ship with photo and film footage. I made my first dives on the wreck in 2018 and have since taken more than 2,000 photos on the wreck. During the five different expeditions (2018-2022) in which I participated, I was able to make 25 dives on the wreck. Located at a depth of 300 feet (92m), diving on the Lusitania is a task not to be underestimated; the wreck is in tidal water and visibility is usually only about 20 feet (6m). The sea can be very turbulent at that location and often dive operations have to be interrupted due to bad weather. The wreck is barely 12 miles (19km) from shore, but it can be a very difficult trip if there is a lot of wind.

New discoveries

The first two expeditions were not easy because of poor visibility and the dangers posed by the many fishing nets on the wreck. I had taken some reasonable images during these expeditions, but it was in 2020 when I got to know the wreck better that I was able to get some really good shots. We also managed to take pictures in the engine room, which had become more accessible due to the deterioration of the hull. The wreck is now rapidly changing and collapsing further due to corrosion and the effects of the current. To put a positive spin on this situation, it means we get to see new angles and parts of the ship that were hitherto unavailable to us, such as the centrifugal pump, of which we had a historical image. Also, advances in camera technology mean we can make images that we could not get in the past.

During the dives I always tried to dive as close to the wreck as possible in order to find hidden elements, like the marble fireplace we uncovered in the beautiful lounge. The marble pieces of the Corinthian column were so well hidden among the other debris of the wreck that had we been surveying on an underwater scooter we would never have discovered them. It takes careful observation to discover items like these. Another important discovery comprised the parts of the central elevator cage. Even though this cage was almost completely destroyed, the parts were still easily recognizable.

In all these discoveries, the help of our expert Stuart Williamson was indispensable. He has been studying the wreck for over 30 years and has an incredible knowledge of his subject. The most important discovery during my dives was in 2022, when my dive buddy Pieter Decoene discovered an intact shoe amongst the wreckage. It almost looked like the shoe was placed there; it was frozen in time. For me it is still the most important photo I have taken on the wreck in over five years.

Important work

One of my main assignments was to take images of the boilers inside the wreck. After the ship was torpedoed and sank, one theory was that the boilers exploded and the ship sank quickly. While it was not easy to find an entrance, one team had succeeded but the images they had made were not of the best quality. I definitely wanted to make better ones. The problem was to find the access on a wreck more than 820 feet (250m) long. My dive buddy Colin Luke Brennan took on the task of laying out a line on the wreck so we could easily find our way back to the ascent line. When we got to the wreck after the descent there was reasonable visibility and we were able to swim directly to where we thought the access was. We were really lucky that dive because almost immediately I saw a large hole in the hull. Inside the hole there were protruding parts left and right, and we had to be careful while swimming in. After a descent of about 33 feet (10m) into the wreck, our eyes had to adjust to the environment but then I immediately saw one of the boilers. Right next to it there was a second one and both were undamaged. One of the boilers had rolled off its frame, but this probably happened during the sinking. Even the pressure gauge on the boiler was still there and the fire door was still open to scoop in the coal. After I had taken a number of shots, the visibility in the boiler room started to deteriorate. It was now time to exit. I went first. Outside on the wreck, I waited a while until my buddy swam back out safely and reeled in his line.

The march of time

During the last expedition in 2022, we had hoped to photograph the ship’s name on the bow but we did not know if the bronze letters were still present. We managed to place our line near the bow on the wreck so we were already close by the time we reached the wreck. Visibility was reasonable and we could get our bearings right away. We swam toward the bow and immediately came to a place where there were large holes in the hull. My buddy did a sign with his lamp and, as I got closer, I saw thousands of bullets scattered here and there. It was part of the four million Remington bullets listed on the payload list. You could also still see in some places parts of the wooden boxes in which they had been packed.

It’s extraordinary how much the wreck has changed in the five years that I have been diving on it. Certainly, this bow area of the hull has fallen apart.

Many other parts were photographed for the first time in 2022, such as the winches on the bow. I have included the 160 best underwater pictures in the book. The photos have also been made available to the relevant ministry in Ireland, who co-manage the wreck. My hope is that new information can be gathered from the pictures to better protect the wreck. The new custodians of the wreck (Old Head Museum) also have a copies of the photographs so that they can be used in the new museum that is planned. In the next few years, the wreck will certainly yield more secrets and perhaps some items can be recovered to show to the general public. The Lusitania continues to fascinate.

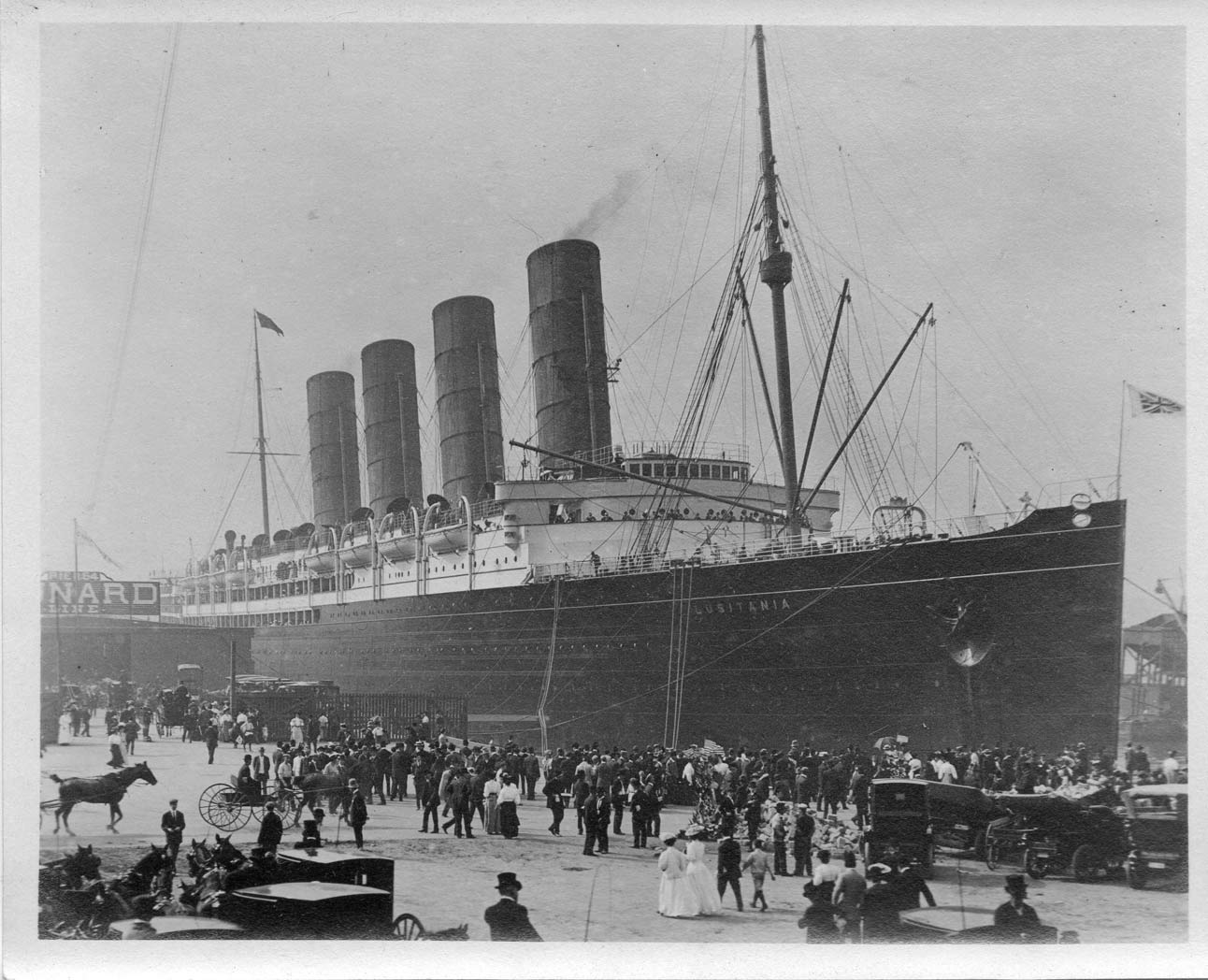

RMS LUSITANIA

Passenger ship CUNARD line

Year built: 1906 John Brown & Company

Length: 787ft (240m) Width: 87ft (27m)

Tonnage: 31550 tons

Propulsion: steam turbines and 4 propellers

Passengers: 1257 Crew : 702

Torpedoed by the U20 on May 7, 1915 (en route from New York to Liverpool)

BOOK

Lusitania – The Underwater Collection

English language

A4 hard Cover

200 pages

160 underwater photographs

240 Historical photographs and illustrations

ISBN: 9789464038071

Price 40 euro – signed and numbered

To order, email: vic.verlinden@skynet.be