Super Aviator

Text by Phil Nuytten

Who hasn’t stuck their hand out the window of a fast-moving car, angled their flat palm and formed fingers up and down, and marveled at the unexpected force of the air-stream? This simple deflection plane is the basic principle behind the control surfaces or ‘airfoils’ of conventional aircraft and, with a much different degree of density and viscosity, those of military submarines. Remember, though, that water is some seven hundred times denser than air. Stick your arm and hand out the ‘window’ of an underwater vehicle moving 50 miles per hour and you may well lose the whole grasping assembly!

The thought of ‘flying’ underwater, just as an aircraft climbs, banks and dives across the sky, is far from a new idea. In fact, the number of patents granted on submarines with full wings and vertical rudders, in the U.S. alone, is quite amazing. D.V. Reid’s 1963 ‘Flying Submarine’ is typical. Thomas Rowe’s ‘Submarine Hydrofoil’ of 1993 claims a submarine vehicle with wings and rudder “either manually or computer controlled by way of hand-held joysticks and foot-rudders”. Well, 1993 is relatively recent; how about Joseph Hardo’s ‘Submarine Flying Boat’ of 1922, or Longobardi’s 1918 submarine-cum-aircraft described elegantly as a “Combination Vehicle”? There are dozens and dozens of these patented designs for ‘flying’ submersibles – some are quite clever and some are not. Reportedly, a few prototypes were built and flown with varying degrees of success.

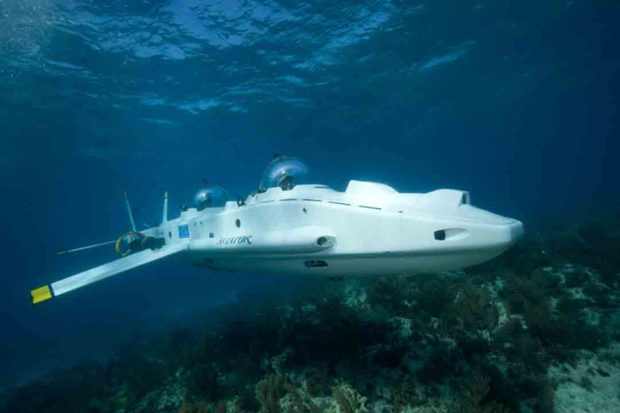

The current batch of ‘underwater aircraft’ has been championed largely by an ex-pat British engineer named Graham Hawkes. He designed several vehicles of this type and has built at least three different prototype versions. The ‘Super Aviator’ trainer used during the Lake Tahoe diving sessions described in the accompanying articles is one such design.

Hawkes’ version of a flying submarine is positively buoyant and relies on a constant amount of down-angle on its control surfaces to stay submerged. If the thrusters stop for any reason, the sub immediately begins to rise to the surface. Conventional submersibles have variable ballast systems and vertical/lateral thrusters that give the pilot the ability to make the sub heavier or lighter in the water – to stop, hover, or sit on the bottom – and to maneuver laterally. The sub then can do a close visual inspection, acquire hi-def video or still images, or operate manipulators to, say, transfer the gold coins from a wrecked Spanish galleon to the subs specimen basket!

The Hawkes subs were built primarily to allow the users to experience the sensation of underwater acrobatics and these subs closely emulate an aircraft in the requirement for continuous forward motion. If an airplane ‘stops’ in mid-air, it falls quickly to the ground. If a positively buoyant sub stops moving, it ‘falls’ to the surface – post haste!

The owners of Sub Aviator Systems Inc. used the positively buoyant ‘Aviator’ and loved the feel of ‘flying’, although Director John Jo Lewis says, “It’s more like a cross between the sensation of riding a high-performance motorcycle and piloting a light aircraft.” But they also wanted to be able to stop and ‘smell the roses’ (or, perhaps, ‘grab the doubloons’!)

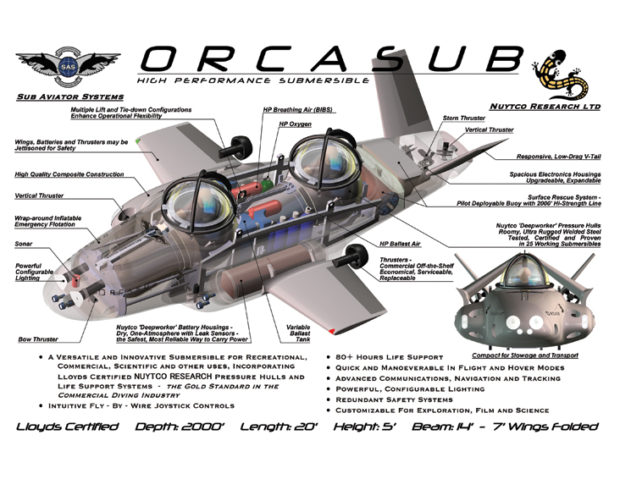

Accordingly, ‘Aviator’ was heavily modified into ‘Super Aviator’ – a hybrid version that can fly, as it had previously, but now contains the stop and hover capabilities common to virtually all modern submersibles. Other additions included a drop-weight system for emergency ascent, and a full ‘self-rescue’ system. The modifications worked so well, that it was decided to commission the development of a new model of a multi-purpose flying submarine. The new design was called ‘Orcasub’ – after the powerful sea-mammals that frequent the coast off the state of Washington where Sub Aviator Systems Inc. is based. Sub Aviator Systems partnered with commercial submersible builders Nuytco Research Ltd., and the final Orcasub design used Nuytco’s well-known and Lloyds certified ‘Deep Worker’ components (pressure hulls, battery pods, etc.) which also serve to increase the depth rating to 2,000 feet (610m) in combination with the wings and rudders of a flying submarine. Super Aviator was retained as an in-house, shallow-water trainer – for demonstrations and for instructing new pilots in the principles of underwater flight.

The original ‘Aviator’ prototype was not classed by a marine certification agency such as Lloyds Surveyors, American Bureau of Shipping, or Det Norske Veritas. The new Orcasub was specifically designed to meet all class requirements and to be certified to the same standards as commercially operated submersibles.

As you can see by some of the patent drawings illustrated, flying submarines are not new – but, certainly, Graham Hawkes deserves full credit for re-awakening interest in this type of machine over the past decade, or so. Orcasub may be the most recent of that small crop but, undoubtedly, won’t the last.

So . . . if you have room on your yacht, or have recently inherited a map showing the location of a sunken Spanish galleon, or just want to fly in the ‘skies’ of the ocean, check out Sub Aviators website at www.SubAviators.com

(P.S. Should you be successful with the map and feel like sending me a doubloon, or two, for putting you on to this – it would be an absolutely lovely gesture and most gratefully received!)