‘There are strange things done in the midnight sun…’

First on deck since the arctic claimed her 150 years ago, Parks Canada underwater archaeologists find HMS Investigator laden with artifacts in the shallows of Mercy Bay, beneath a diminishing polar ice pack.

Text by Peter Golding

Sam McGee from Tennessee ‘was always cold, but the land of gold seemed to hold him like a spell’.

Times change. Staking a claim for the yellow metal nuggets of Sam’s gold rush obsession isn’t today’s arctic imperative though a ‘dig’ up north remains cold work, even as the mercury rises.

Poet Robert Service and his character Sam McGee (a real person) would be tickled to learn that today, ‘the men who moil for gold’, are shipwreck hunters and divers searching for archaeological treasures. Once found, the sunken relics will help unravel a 165-year-old mystery, write the ending to a dramatic chapter in Canada’s arctic history and, for good measure, their discovery will serve the country’s present day geopolitical interests.

And it’s a ‘cool’ diving story in pretty much every sense.

E,T Where Are You?

Last year (DIVER September 2010) we told you about a multi-disciplinary hunt for the lost Franklin ships, Erebus and Terror, prominent in early arctic exploration, and also about the discovery of HMS Investigator, one of several ill-fated search and rescue ships dispatched by Queen Victoria in the wake of the Franklin vanishing of 1845.

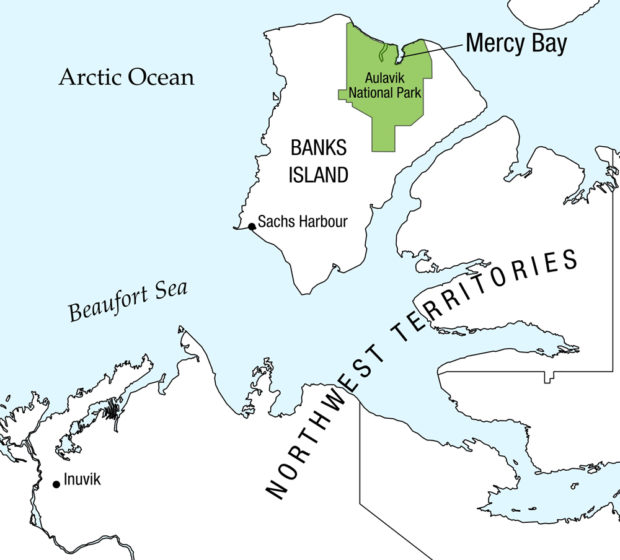

It was Sir John’s third attempt to forge the faster, more lucrative, top-of-the-world trade route to the Far East. Sadly, Franklin failed and perished, along with all 129 crew under his command. In the years that followed more than 20 rescue missions also failed in their primary objective to locate his ships, which remain lost to this day, though the accomplishment of HMS Investigator is worthy of note. Because it approached and mapped the arctic from the west through the Beaufort Sea and eastwards to Banks Island and Mercy Bay where it sank, the vessel did navigate the final leg of a Northwest Passage, and most of her crew lived to tell the tale. In that sense her voyage was a high point in Great Britain’s golden age of maritime arctic exploration.

All this arctic drama was long over by 1907, when Robert Service published his memorable poem immortalizing Sam McGee, yet the fanciful yarn echoed the perilous truth known to generations of northern explorers:

‘The arctic trails have their secret tales

That would make your blood run cold’

Though its geography and the vagaries of the shifting ice are less of a mystery today, this harsh environment is now regarded by many as ground zero in a climate debate that, pardon the pun, has polarized world opinion from one ice cap to the other. While long-term consequences of the big melt remain unclear, a short-term outcome of diminishing ice cover allowed for the Mercy Bay survey and discovery of HMS Investigator in the summer of 2010.

This summer marked year three of the federally funded Franklin search, which further narrowed the target area and allowed the Canadian Hydrographic Service to chart new territory, but there was no ‘paydirt’ in the form of Erebus or Terror showing up on a sonar scope. Building on its two previous search seasons the survey team this year also deployed Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) technology, which collects bathymetric data from an aircraft, and can identify shipwrecks. Once analyzed this data may yet reveal the Franklin ships.

Midnight Thrills

Meeting the project’s other objective, Parks Canada underwater archaeologists investigated the Investigator just 36 feet (11m) deep off the shores of Aulavik National Park, logging 105 plus dives on the virgin wreck over the span of two early July weeks.

And in the spirit of strange things done in the midnight sun, the dive team found itself descending frequently in the dead of night when the water was calmer and conditions more conducive. But they were not your typical ‘night’ dives. During summer months at these latitudes the sun remains visible 24 hours a day, hence ‘the midnight sun’.

“I assure you those dives were a thrill,” Marc-Andre Bernier told DIVER. The head of underwater archaeology for Parks Canada, Bernier said after an hour bottom time in 28F (-2C) water it was, “a little chilly, but exploring such an exceptional wreck and then surfacing at 1 a.m. in the midnight sun was unprecedented and a highlight for all the divers.”

The six person team comprised five Parks Canada divers and one from its sister organization, the US National Parks Service. Routine had two, two-man teams in the water at a time with the remaining two topside as safety diver and dive manager. Typically, they would log four sets of single tank dives daily, beginning between 9 .a.m. and 10 a.m. and, without the constraint of a setting sun, would continue through until 1 a.m. to 2 a.m. the following day.

Their main preoccupation was safety. “The diving wasn’t that difficult,” Bernier said, “but the site was remote, two to three days away from emergency facilities, so we took extra precautions to avoid problems.”

Among these was the decision not to penetrate the wreck. When Investigator was discovered in the summer of 2010, an ROV survey provided a preliminary video record of the ship and surrounding area. This summer’s mission was to “evaluate her archaeological potential,” Bernier said.

Diving the wreck firsthand revealed more than the ROV’s camera had recorded the previous season. “We saw many more openings below the main deck though none would have allowed a diver to enter, not that we’d have done that anyway,” he said. To gain a better understanding of the inside condition of the 19th century sailing ship the team had rigged camera and lights on a rod that was inserted at various points. The images revealed a lot of sedimentation. “At least halfway into the below decks area was covered by silt that prevented us from seeing artifacts,” Bernier said, “but this also tells us that whatever is inside is extremely well protected because these are the best conditions for preservation.”

He said the team was “really surprised to see such a large number of artifacts strewn across the main deck… many more than we thought we’d find.” A decision was made to take some of the easily retrievable artifacts for study and protection since they were exposed and threatened by conditions. In all, the team recovered 16 artifacts, among them a rifle and sailor’s boot, from which scientists are already collecting data.

Bernier said that perhaps the most important of the items recovered was some of the copper sheathing used to protect the ship’s hull from marine organisms. “This can be compared with the copper found at Inuit sites to see if it can be traced back to the Investigator or other arctic sailing ships,” he said. Importantly the copper analysis also helps in the broader Franklin investigation since there’s indication sheathing was removed from Erebus and Terror during their ordeal in the ice pack to the east.

Topside Clues

During the Investigator exploration in Mercy Bay there was also a land-based search underway on adjacent Banks Island. Two locations were scrutinized, McLure’s Cache near the shore, and another much older Paleoeskimo site. Robert McLure was captain of HMS Investigator and the cache was made during his crew’s time in the area and before they abandoned ship for other British naval vessels that had arrived in the vicinity and which they reached by overland route before ultimately returning home after some three years entrapment in the western arctic.

Among interesting artifacts unearthed at the cache site was a tin can, very old and the best preserved of any they have found to date. “It was inscribed the same as another found at an Inuit site 375 miles (600km) away,” Bernier said, adding that all the discoveries contribute to their understanding. The cache site is also marked by the graves of three crewmembers.

The second locale under study was the Thule Inuit archaeological site more than 2,000 years old and even richer in artifacts than anticipated by the team. The Thule people were immediate ancestors of the Inuit.

Also investigated this summer was site of an observatory on the west side of King William Island, to the east of Banks Island, set up by Franklin and used by his crew between 1846-48. An 1859 search party looking from Franklin ship survivors was first to explore the encampment and archaeological work since then has established that the observatory was close to Franklin’s ships; the point where the crew abandoned them and from which, in time, they drifted in the ice before sinking to their separate and still elusive grave sites.

The arctic expedition this summer was the last in a three-year plan funded by the federal government. Partnered with Parks Canada and the Canadian Hydrographic Service in the multi-disciplinary search in July and August were the Canadian Coast Guard, the Canadian Ice Service, the Government of Nunavut and the University of Victoria’s Ocean Technology Lab.

It Ain’t Over ‘Til It’s Over

Asked if the search would continue next year, Canada’s new (since last year’s expedition and discovery of HMS Investigator) Minister of the Environment, Peter Kent, said, “Why would it not?”

Parks Canada expenditures over the three-year program amount to approximately $275,000. In addition there are the costs incurred by participating partners contributing services ‘in kind’ through their routine arctic operations. The Minister, also responsible for Parks Canada, said future plans would depend on resources available. Though expeditions have not yet been formalized, he said, “I assure you this will be an ongoing project.

“This is not only a mystery of heroic tragedy for Canadians,” Kent said of the Franklin story, “this is an expedition that’s fascinated people the world over for centuries so there’s great interest in locating these national historic sites and providing science and interpretation of what in the end happened to Franklin, his crew and his ships.”

Franklin’s ships Erebus and Terror are unique in Canada as designated national historic sites that remain to be located.

A closing note: I think it fitting for all of us interested in the underwater world and its preservation to salute Parks Canada – the world’s first national parks service – for pulling off this exotic, spirited and challenging shipwreck exploration in such a remote locale 375 miles (600km) north of the Arctic Circle, in 2011, on occasion of its 100th birthday. It was an uncommon achievement – that happened underwater – to mark, and stand as a highlight, of the Parks Canada centennial year. From all of us at DIVER, congrats!

Parks Canada: Well Preserved at 100!

In 1911, Canada showed foresight and leadership as the first country in the world to establish a national service entirely dedicated to parks. One hundred years ago, few Canadians realized the impact of this decision, but they soon would come to know the iconic places that were held in trust for them, places such as Banff and the Fortifications of Québec, that would become world renowned symbols of Canada.

In 1911, Canada showed foresight and leadership as the first country in the world to establish a national service entirely dedicated to parks. One hundred years ago, few Canadians realized the impact of this decision, but they soon would come to know the iconic places that were held in trust for them, places such as Banff and the Fortifications of Québec, that would become world renowned symbols of Canada.

Today, as we embark on a second century of caring for our nation’s natural and cultural heritage, Parks Canada manages an impressive network of 42 national parks, 167 national historic sites and four national marine conservation areas. These fascinating places protect what is fragile but vital: the unique, unrivalled and irreplaceable places where Canadians can connect to their heritage and the wildlife, landscapes and waters that are the very essence of Canada.

Canada’s motto is A Mari usque ad Mare – From Sea to Sea. Nowadays, we tend to include our third sea, the Arctic, as well. Bordering three oceans and the Great Lakes, Canada enjoys the longest coastline in the world. The vast marine environments off these coasts, varied and productive, have played a major role in shaping Canada’s history and economy. So it’s no wonder that national marine conservation areas symbolizing this powerful force are an important component of Parks Canada’s network of nationally significant places.

Fathom Five National Marine Park, established in 1987, was Parks Canada’s first large-scale marine protected area and launched a system of national marine conservation areas that is still being developed today. More biologically and culturally rich areas, like Lancaster Sound, home to most of the world’s narwals and a third of North America’s belugas, are currently being considered.

For more go to www.parkscanada.gc.ca