Adventure Wanted

Only whales and whale sharks need apply

Text and Photography by Michael Wood

SCUBA diving or snorkeling with any kind of whale or a whale shark remains high on my adventure bucket list, though I had what you might consider a close ‘second’ on the excitement scale with something whale-like 20 years ago in the clear waters of the south Pacific, off the Hawaiian island of Oahu.

The Situation

It was 1994 and I was the Officer-in-Charge (OIC) of the SEAL Delivery Vehicle Team ONE (SDVT-1) Detachment, based on Ford Island in the middle of Pearl Harbor. I supervised three Dry Deck Shelter (DDS) platoons, one SDV platoon, one visiting SEAL platoon and a headquarters staff. I mention this because my position at the time allowed me to oversee, and to participate in, some combined Naval Special Warfare (NSW) and submarine operations that were taking place in the area. The USS Kamehameha (SSN642), KAM for short, was the boat involved, a 425-foot (130m) long 33-foot (10m) wide former ballistic missile submarine converted to carry dual deep submergence hyperbaric DDS systems, which are essentially submarine garages fixed to the deck to hold one or two SEAL Delivery Vehicles or wet submersibles.

The Opportunity

The Navy needed still photos and video of the upcoming NSW and submarine operations to demonstrate the benefits of converting more missile submarines, of which the next four were Trident-class, for special operations missions. As the OIC and NSW Task Unit Commander, I worked with the submarine Commanding Officer and his Submarine Squadron Commander to schedule a full day for photographic documentation of the operations. This activity was out of the ordinary in such ops, but we all agreed the planned shoot would benefit the conversion program. Casting for this operation was the easy part. I’d be shooting the stills and from the civilian world a professional videographer named Bernie Campoli would handle the filming. Bernie had done this kind of thing before and I had worked with him on occasion.

The Preparation

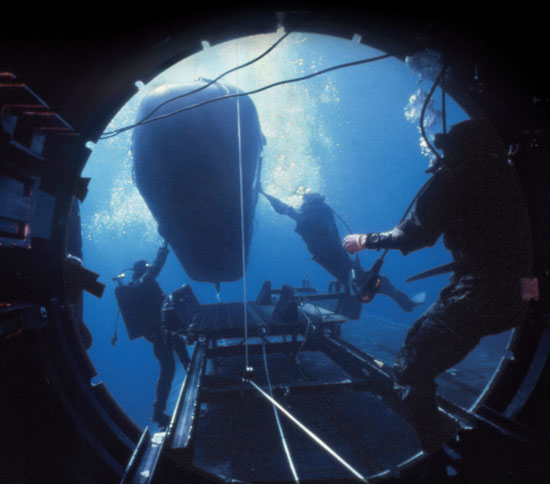

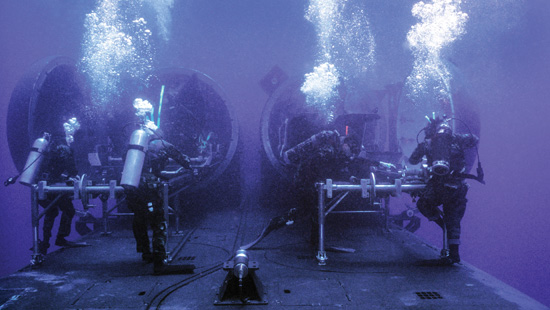

Two Dry Deck Shelters were loaded on board the KAM for planned simultaneous operations. The DDS is a removable three-module hyperbaric system that allows divers easy entry and exit while the host submarine is submerged. These subs are specially modified to accommodate the DDS units that are configured with appropriate mating hatches, electrical connections, piping for ventilation, air for divers and the ability to drain water. They’re pretty big at 38 feet (11.5m) in length and nine feet (2.7m) in diameter, each weighing in at 30 tons. On this occasion the hangar modules were loaded one housing a 20-foot (6m) long SDV, the other packed with four 16-foot (5m) long inflatable combat rubber raiding craft (CRRC), each equipped with outboard motors.

The Planning

The simultaneous DDS operations meant that both nine-foot (2.7m) diameter doors would open at the same time while the vessel was underway. As it cruised, the DDS track and cradle would roll the SDV out onto the submarine deck for launch and recovery, followed by launch of the rubber raiding craft from the second DDS, along with the SEAL combat swimmers who would navigate them to their objective in a real operation. Purpose of the concurrent DDS operations was to demonstrate that the host submarine’s water pumping and pressure tank systems could handle the massive amount of water movement required to flood and drain both DDS hangars and to demonstrate that the sub’s ballast and trim could handle dual DDS operations in at-sea conditions. Operationally, the exercise would demonstrate the significant reduction in time required to launch and recover a SDV, four CRRCS and 24 SEAL combat swimmers, as compared with normal NSW/submarine operations.

If all that wasn’t complex enough, we had to plan now for two film crew divers shooting the operation to ascend to the surface at a predetermined time, load into a support boat and race ahead of the KAM as it cruised underwater at two knots. When we were in position, Bernie and I would then drop back down to 50 feet (15m) ready to film and photograph the 425-foot (130m) long USS Kamehameha as it approached and passed us, our cameras rolling to complete the photographic mission. Bernie and I choreographed every detail of the film and video plan, which received the blessing of the overall operational commander.

The Operation

The initial stage of our plan was executed without a hitch. Both DDS systems were flooded, both doors opened and both track and cradle systems were rigged out simultaneously with precision teamwork. Following the deployment, Bernie and I surfaced according to plan to board our support boat. Bernie was handling a large yellow underwater video camera in its housing, complete with lights, and I was carrying three separate Nikonos underwater camera systems, each equipped with a wide-angle lens and two of them rigged with dual strobes. One of these systems was a brand new, and very expensive, Nikonos RS – the first of its kind single lens reflex integrated underwater camera. I looked like Mahakali, the many-armed Kali Hindu goddess, trying to swim underwater.

At the surface we loaded into the support boat without incident. We then had to guide it ahead of the KAM, traveling at two knots at periscope depth. We knew the course, heading and speed of the KAM, but on the surface, trying to guide on a single point of reference (the periscope), it’s shockingly difficult to predict distance and heading, even when you know the submarine’s length. Trigonometry was not going help in this case.

In position we agreed that by the time we descended to the appointed depth we’d be in an ideal location to shoot the submarine as it approached. We rolled into the water from opposite sides of the boat, each in standard SCUBA gear and carrying our respective camera systems. Bernie was to swim to one side of the sub and I was to swim to the other. It quickly became apparent to me that I was not the many-armed Kali goddess. Had I been I wouldn’t have had to watch helplessly as one of my expensive 15mm wide-angle lenses waffled irretrievably into the blue abyss. The lens had popped off as I hit the water, instantly flooding the Nikonos V body to which it was mated, a tragedy made only slightly less painful by the knowledge that my Nikonos RS and other Nikonos V system were safe and functional.

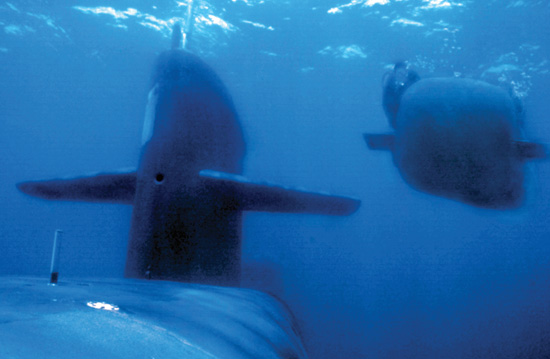

Coping with this loss I was struck by the vivid realization that the KAM was already directly below us. To get into position ahead of the sub would require swimming at a speed of at least 2.5 knots. Luckily I was in good shape back then and was able to get in front of the vessel with just enough time to snap two photos of it coming directly at me. With my camera and strobes set in advance all I had to do was get in position, point and shoot.

After this I had time to look around and spied Bernie filming away on the other side of the sub as it cruised by. It was then I had my ‘artificial whale’ experience. Blue whales can reach almost 100 feet (30m) and look equally impressive as they navigate the infinite blue of the ocean. Though longer, the KAM is a similar colour and so the whale image came to mind. Cruising by on its steady course it also seemed like some endless underwater train, against which I felt like an ant. At deck level I hovered in awe as the behemoth cruised by oblivious to my presence. What an experience! All the money in the world couldn’t buy that and there I was getting paid to do my job.

Bernie was visible on the starboard side as the long bow of the submarine passed, followed by its rising ‘sail’ with fairwater planes. The silence was eerie; you’d think such a big machine would be accompanied by a similarly big sound, but all I heard were my exhaust bubbles. A moment later I saw the massive DDS units on the aft deck, their doors still open and the track and cradle systems rigged out from the exercise. The SDV had already launched and by nothing more than lucky timing I was able to photograph its maneuvers over the sub’s sail planes, a sequence you couldn’t have hoped to capture even in the most optimistic of plans. I continued photographing the submarine and before long its stern was in view and as it passed I watched her screws turn in what appeared to be slow motion, like the seconds hand moves on a clock. Amazing, I thought, that such a slow rotation maintained two knots headway for such a massive vessel.

Our job was done and so Bernie and I joined up in the water, after the sub passed, and we surfaced to the support boat without losing anymore camera gear, I’m pleased to report. To this day my submarine experience remains a highlight of my military career and I still have a real whale encounter to look forward to.