Australia’s Marine Superhighway

Ocean inhabitants traveling Australia’s marine superhighway have made this rest stop a dive site that doesn’t disappoint at any time of the year

Text by Lilla Clare

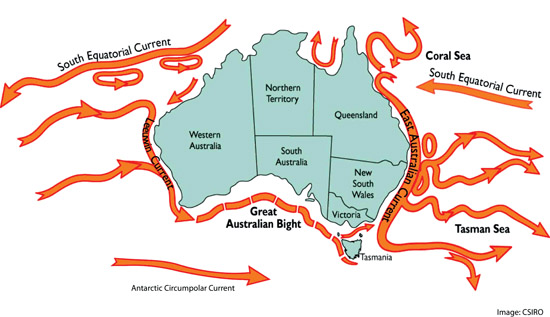

Just 1.73 miles (2.8km) off the eastern-most point of the Australian continent, there’s an unassuming little outcrop called Julian Rocks. By chance its position in Byron Bay is dead centre of the three Pacific ‘elbows’ of the East Australian Current (EAC), an enigmatic underwater freeway that’s rare, not least for its immense size. From surface to seabed, the 124 mile (200km) wide, 1,640-foot (500m) deep, ‘water tunnel,’ churns an incredible 30 million cubic feet (10 million cubic metres) of water per second southwards along the entire east coast of Australia.

A satellite view of these mega currents conjures the image of giant octopus tentacles, the continent firmly in their grip. Flowing at an average speed of 4.6 mph (7.4 kph), they create massive nutrient rich upwellings that attract an endless parade of marine life from the vast Pacific, the tropical Coral Sea to the north and from the chilly Tasman Sea to the south. This confluence of hot and cold waters, where marine life from these wide-ranging ocean temperature zones all come together, is uncommon and makes it a standout in our water world. From schools, pods, and bait balls, on down to solitary cruisers, all take the EAC off-ramp to congregate and feast near Julian Rocks. Here hungry wrasse and other cleaners, like pit stop crews poised for action, await deliverance of the feast that sustains them, the parasites hitching a ride on their hosts.

This region of New South Wales exudes a timeless, even mystical energy that’s sacred in Aboriginal culture. Protected and world heritage-listed, the ‘Rock’ – as Julian Rocks is affectionately known by locals – has been a marine reserve since 1982. Indigenous Bundjalung people know Julian Rocks as ‘Nguthungulli’ (Father of the World), the creator of land, water, animals and plants in Aboriginal Dreamtime. According to legend, he resides in a cave at Julian Rocks, the creation myth of which recalls a jealous husband in pursuit of his wife and her lover, fleeing the mainland by canoe. His spear misses them but hits the canoe, which breaks in two and sinks, leaving the two ends protruding from the surface, as the rocks appear today. Given its status as a sacred landmark, custodianship is shared, informally, by the Australian Government and the Aboriginal people.

European settlement came on the heels of Captain James Cook’s first voyage into this “somewhat treacherous bay”, in 1770. Unwittingly, he also discovered the EAC, after noting that his barque, HMS Endeavour, was “in a southward drift off Cape Byron, despite fresh winds from the south”. In fact, it took him another six years to officially name the Cape after Lord Byron’s grandfather, navigator Admiral John Byron. The two rocky islets were long known as Juan and Julia rocks, after Cook’s niece and nephew. Officially, they became Julian Rocks in 1971.

Over the last half century, the region has undergone big change… for the better. The 1960s saw start of this transition from damage caused by intense whaling, logging and other resource industries to a more ecologically friendly long board surf culture and new era of prosperity and rejuvenation.

Subsea Diversity

With year-round water temperatures in the range of 64 to 75°F (18-24°C), these pleasing and now protected (from commercial fishing) waters attract a wide range of ocean critters that almost seem to understand they’re in a safe zone and that divers are not a threat. These include Humpback whales, dolphins and all kinds of sharks – Grey Nurse, Leopard, Ornate, Spotted and Wobbegong. Many, if not most, of these animals are present year round. Large numbers of rays also show up to eat, hang out and mate. Among them are Australia’s reef manta (Manta

alfredi), Sting, Eagle, Shovelnose (something called Stingarees) and larger Bull rays.

And, true to scenes from that endearing big screen flick Finding Nemo, there are plenty of turtles. Fans are drawn from around the world by these bodacious ‘motor-homers’ who are ever present on the EAC open road. Among them are the Hawksbill, Green and (endangered) Loggerheads, returning to the islands of their birth at Mother Nature’s bidding to lay their precious eggs.

Sunrise over Byron Bay is always striking, and today the light is reliably magical as we prepare for the dive ahead. The locally operated rigid-hull inflatable, Moby Duck, is ready for launch through beach surf and our collective heave-ho to breach the breakers builds immediate camaraderie in the group. We’re all chatting and chuckling by the time we’re aboard and underway. Heading seaward to the northeast we view Byron Bay’s iconic lighthouse, gleaming white in the early morning sun. Weather and water conditions here can change quickly. Yesterday, it was flat calm. Today, it’s choppy. This is all part of the Julian Rocks experience, which can see you submerge under sunny skies and surface in the midst of a tropical thunderstorm.

We quickly approach Julian Rocks. A geologist will tell you that those craggy, ‘canoe ends’ are metamorphic outcrops of Rocksberg Greenstone, Bunya Phyllite and Neranleigh-Fernvale formations. To divers, keenly awaiting arrival of the many marine species here, these craggy little outcrops are simply a place of rare beauty. And diversity: from delicate coral gardens to jagged rocky ledges, from caves and trenches to sandy shoals, from deep oceanic reefs to drop-offs to ‘bommies’ to towering pinnacles. Julian Rocks has them all.

Together these divergent seascapes present an over-stocked aquarium, a quirky cornucopia of over 1,000 documented finned species of tropical, temperate and pelagic fish… and the count continues! Beneath this movable feast for the eyes, and the underwater photographer, is a multi-hued macro-muck diving Mecca. Every inch of rock is covered in some form of life, from invertebrates, arthropods, echinoderms to the ever-exquisite flatworms and flamboyant nudibranchia.

Tropical or Temperate

It’s late autumn, the time of year when water and air are both a comfortable 75°F (24°C), perfect for leopard sharks and reef manta rays. The excitement is palpable as we gear up, the chatter and squawks of cormorants and shags on the rock filling the air. In the hundreds, these birds have come to court, fish and laze in the early morning sun, and we’re the entertainment. Cameras are soon passed to divers already in the water. One accomplished shooter on the dive is Christine Hamilton, who’s big on Julian Rocks for its diversity. “The range of creatures in such a small area means I’m never disappointed,” she says. “And ‘the rock’ is so familiar. I never get lost.” Many others agree. This unassuming little outcrop attracted 14,000 divers last year alone.

But day one is cut short. From where we are on the water it’s easy to see why our second dive isn’t going to happen. The surge is pretty wild on the eastern side. Huge breakers thunder through the gap and the swell is picking up. But we’re in good hands: our dive masters and boat operators know the ever-changing conditions well. On calm days, Julian Rocks is a snorkelling’ Shangri-La, enjoyed by some 6,000 each year in addition to the SCUBA crowd.

When we do get back in the water, we dive to the bottom of a shallow reef on the sheltered western edge to a site called The Nursery. There’s hardly any current, but visibility is low. This place is a favourite for fish and the photographers who like to shoot them. It’s shallow and sheltered, offering good natural light that makes for decent available light imaging when dodgy visibility adds too much strobe light backscatter to the equation.

I can never decide whether this place feels temperate with tropical overtones, or tropical with temperate undertones. Either way, the diversity of life down here doesn’t discriminate. As we reach the bottom, I notice that there are invertebrates everywhere and one of our group, Samuel, spots an elegant little cuttlefish in a colourful crevice.

At 39 feet (12m), we round a wall to find a sheltered cove filled with hundreds of black-tipped bullseyes. Disturbed by our intrusion, they take two marvellously yellow minutes to pass. That’s not all: schooling above them are beautiful white trevally and in the same moment we see a solitary manta heading for a bommie cleaning station, complete with cleaner wrasse entourage. It swims effortlessly from the depths, cephalic lobes open, feeding.

Seeing big animals is always a thrill. We watch as it banks into a series of graceful loops, passing us at arms length on each circuit. We’re left breathless. Then, diving deep, it returns in a slow upward fly-by and makes a final loop over the cleaning bommie. Heading back onto the EAC expressway, it crosses the path of a huge Blue Easter Groper before fading into the blue. It was a dream encounter; the kind that often defines a trip and that makes our sport so amazing.

Next I see a pair of long-legged crayfish angling along the bottom, which is covered in little tropical delights that constantly dazzle and flash their neon patterns as the crustacean passes by. Then another treat: a little crab, impossibly colourful and nestled in a purple-tipped anemone. The contrast is striking and it jigs about as if to catch my eye and say, “Hey, check me out!” We decide to stop swimming and just sit on the bottom for a while to take in the kaleidoscope of life immediately before us (and all around, if we turn our heads) and observe the leopard shark that’s just settled down a short distance away.

Getting Hooked

Conditions continue to calm down as the days pass and so we head for Cod Hole (not to be confused with the well-know Potato cod site on the Great Barrier Reef) on the northern most point of Julian Rocks. Here we find a cave; it’s 70 feet (21m) down and goes about 30 feet (10m) in. But this isn’t just any cave. We’re told it’s one of a dozen sites essential to the survival of Australia’s Grey Nurse sharks that migrate up the coast from the cooler south to rest and feed here. A few have already been seen in the vicinity and they’ll come in droves to feed and mate during the winter months. Cod Hole is spectacular today. Tropical storm run-off from the mainland has spiked these near-shore waters with nutrients that attract massive schools of deep ocean temperate fishes, such as sweetlips, red morwongs, bullseyes and barracudas. The place is alive with baitfish, glassfish, saw tails, jewfish, goatfish, fusiliers and turtles by the dozen. The EAC reliably delivers them all! Then we’re off, finning our way southward to Hugo’s Trench, a deep gutter running between Julian’s two rocky islets about 50 feet (15m) down. Cruising through this channel are deep sea bream, huge Blue Eastern gropers and surgeonfish in the company of sharks and rays of many kinds. A fisheye lens is needed to capture this wide-angle vision, but there’s so much happening it’s hard to know just where to point the camera.

We push southwards to The Needles, where the rock formation morphs into an intricate series of deep ocean walls, canyons and pinnacles that are home to even higher concentrations of marine life than Cod Hole! It’s the only place I’ve seen a huge bull ray, manta ray and leopard shark together and, as it turned out, all willing to pose in the same photo. It’s no big surprise that the biodiversity of this place makes it the home of a prestigious underwater photo shootout each year. The annual competition attracts professional shooters from around the world. Local judge, author and photographer John Natoli says Julian Rocks is a natural for such a contest. “I still get excited diving here after a decade and more than a thousand logged dives,” he says. The diversity is extraordinary, and year round, he emphasizes. “Under 71°F (22°C) you’ll be diving amid hundreds of Grey Nurse sharks with the constant sound of whale song in the background; above 71°F (22°C) you’ll be diving amongst just as many Leopard sharks with regular visits from Manta rays and fish life so varied in species and size that the intensity of the experience never lets up.”

There’s no doubt that it’s easy to get ‘hooked on Julian Rocks’, which happens to be the title of John’s outstanding book of photography. Just one dive is all it takes. The icing on this cake is that diving at Julian Rocks takes you to Byron Bay, one of Australia’s most appealing holiday destinations. The scope of experience you can look forward to in this dreadlocked-township is every bit the equal of the underwater experience that awaits. You may even enter one of your own magical memories if you’re in town during competition week. Who knows, you just might win something! At the heart of the East Australian Current anything can happen.

And that’s really true. As we surface from our last dive a pod of about eight dolphins arrives to play with us. They’re always surfing the waves alongside board riders and when they’re in closer to shore they make a point of checking out the dive boats. Each day has

its rewards!

Julian Rocks – The Diving Details

Average depth 49 to 65 feet (15-20m)

Average visibility 32 to 65 feet (10-20m)

Annual water temperature 64-75°F (18-26°C)

Thermoclines can cool things down in winter. Sharkskins recommended. Currents can be strong and conditions changeable. Always check ahead.

There are three dive operators running up to three trips daily, seven days a week. Boat trip duration approximately 10 minutes from shore. Open to SCUBA divers and snorkelers. Nitrox is not available locally.

www.sundive.com.au

www.byronbaydivecentre.com.au

www.bluebaydivers.com.au