PADI on rebreathers: Are they safe for recreational divers? Pt1

The world’s largest dive training agency thinks they are, and they’ve developed courses for the rec and tec diver alike. Here, the agency’s Vice President of Rebreather Technologies, Mark Caney, weighs in on PADI’s new direction, the rise of a new ‘Type-R’ recreational rebreather, and the voice of opposition.

Interview conducted by DIVER contributor Michael Menduno

As the singularly dominant organization in the $3 billion worldwide sport diving market boasting nearly 6000 affiliated dive stores and resorts and over 135,000 members, it’s not surprising that privately held PADI Inc., the self-proclaimed “way the world learns to dive,” is one of the most closely watched and talked about companies in the business.

For the last twenty-plus years, ever since the advent of technical diving, PADI has relied on others—“Brand X” in PADI parlance— to bring technological innovation to the market though keeping a careful eye on their progress. Once a sufficient market develops, PADI moves in to adopt, promote and profit from the innovation, often times to the dismay of competitors.

While enriched air nitrox (EAN) diving was introduced to sport divers in the late 1980s and early nineties, PADI waited until 1995 to introduce its own EAN program to its members. Now its PADI’s best selling specialty course. Similarly, throughout the nineties, PADI watched the development of technical diving from the side lines, but didn’t launch its own TecRec program until 2000, and then only after several technical training agencies launched their own competing recreational training courses.

PADI was also one of the sponsors of Rebreather Forum 2.0, which I organized with Tracy Robinette in 1996, and published the proceedings through its Diving Science & Technology subsidiary (available at http://rubicon-foundation.org/). But outside of a marginally successful Dräger Atlantis semi-closed rebreather specialty course (the Atlantis never took off), PADI essentially remained out of the loop on rebreather technology, which until recently has been a tool used almost exclusively tool for high end technical diving.

Now the California-based marketing juggernaut is taking the lead in helping define and aggressively market rebreather diving for recreational divers—an essentially untapped market where tekkies and the rebreather manufacturers who support them have heretofore feared to tread. PADI announced its new recreational rebreather courses last September and is now working to populate its rebreather instructor ranks.

The company is also organizing a high profile industry conclave, Rebreather Forum 3.0, with the Divers Alert Network (DAN) and the American Academy of Underwater Scientists (AAUS), this spring in Orlando, Florida. to help advance the state of the art, and presumably help establish a leadership role in rebreathers and continue to build the brand. Arguably the move into recreational rebreathers is consistent with PADI’s strength of bringing diving to the masses, but at the same time it’s not without controversy.

Advocates such as James Roberton, the executive vice president of sales at Poseidon Diving Systems AB, which has invested more than $5 million creating a rebreather for recreational divers, say that offering well-heeled divers the ability to double or more their no-stop bottom times and truly enjoy the ‘silent world’ sans bubbles, will revolutionize sport diving, which has been in decline for more than a decade.

“Without innovation there’s no interest or excitement, and no real growth,” Roberton says. “The current dive business is based on 60-years old technology!” He compares recreational rebreathers to snowboards, introduced to a stagnant ski industry in the late seventies and early eighties; though resisted at first, the technology attracted needed young people to the sport, which then grew by a factor of 60 times in the ensuing 25 years.

Conversely, critics are concerned that with their complexity, high maintenance, and a fatality rate that may be as high as five to10 times that of open circuit scuba (no one knows for sure), the benefits of closed circuit rebreathers, which are statistically 20 times more likely to fail than scuba, simply don’t justify the risks for recreational divers who lack the necessary skills and experience. As a technical rebreather manufacturer cautioned, ”We know that complacency kills. What I worry about is that many recreational divers are complacent times a hundred.” The community is concerned that an increase in recreational fatalities would hurt the diving business as a whole.

However, the issue may ultimately come down to the question of whether manufacturers like Poseidon and others can successfully build a new generation of user-friendly, fault tolerant rebreathers that will monitor the user’s breathing gas, scrubber and other systems better and more accurately than a trained diver can, and in case of a problem, alert the diver and act to keep him or her alive.

Calm and Thoughtful

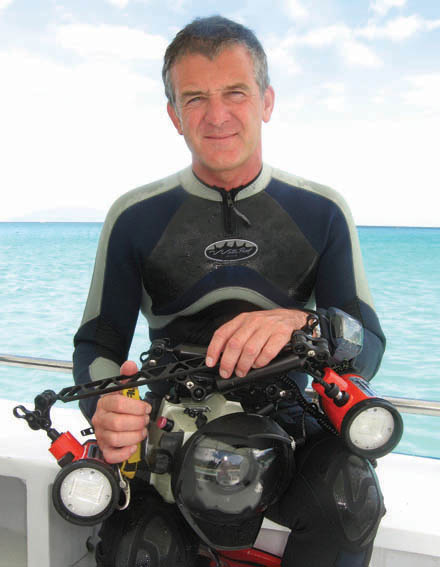

Mark Caney, the British-born, 54-year old vice president of rebreather technologies at PADI is convinced that it is not only possible, but that next-gen rebreathers are here, or just around the corner. Caney is the architect of PADI’s new rebreather programs and also oversees PADI’s technical diving program. He exudes a calm, thoughtful, confident manner when answering questions peppered with his dry British wit. When I asked him what rebreathers he dived, he cocked his head slightly and gave me a quizzical smile. “Michael, I’m the vice president of rebreather technologies,” he said, emphasizing the plurality. “I dive them all.”

Like many of his generation who grew up watching Jacques Cousteau, Caney had no trouble recalling his first experience underwater. He was eight-years old and discovered a water-filled horse trough while walking in Somerset. He ran home, got a pair of empty jam jars, returned to the trough, held them to his eyes and stuck his head underwater. “Things started moving about below me,“ he explained. “I saw water boatmen and little pieces of weed and stuff. There was a whole world down there.” He says that experience shaped his life. His parents bought him a mask with built-in snorkel and from then Caney was under water every chance he could get.

At 18, He enlisted in the British military and got certified at the local BSAC club on his base in Northern Ireland. A couple years later he was transferred to Cyprus, and realized it was ideal place to “support” (his words) a dive store, before Cyprus became a dive destination. After completing his service, Caney found several partners and opened CyDive – Cyprus Dive Centre in 1980. It was the second dive store on the island. PADI was just getting starting in Europe, and Caney saw it as a business opportunity for the store. He became a PADI instructor in 1983, and a course director in 1986.

The late 80s and early 90s were heady days in the diving business. The demand for PADI instructor training was booming in Europe and the Middle East and nitrox and technical diving was just emerging. Caney saw it as an opportunity. He sold his interest in CyDive and hit the road as a self-employed PADI and American Nitrox Divers, Inc. (ANDI) instructor trainer offering both PADI rec instructor training, and ANDI ‘SafeAir’ (nitrox) instructor and blender training and helped dive centers set up nitrox filling stations. ANDI CEO Ed Betts said that Caney, who was ANDI Instructor Trainer #13, was an astute businessman and one of ANDI’s top producers. During that time, Caney trained to be a tech diver with Betts and fellow Brit, the late tech pioneer Rob Palmer.

After six years on the road, Caney decided to leave self-employment behind and become a company man. In 1996, he joined PADI as the vice president for training, education and membership, and got involved in PADI’s enriched air nitrox and TecRec program. Today he holds a dual vice presidency and is based out of PADI’s Bristol, UK offices.

Outside of his duties at PADI, the avid underwater photographer and skier retains his BSAC national instructor status and he is also the current president of the European diving standards body, the European Underwater Federation (EUF). The eclectic waterman also had his first novel, Dolphin Way: The Rise of the Guardians, which was six years in the making, published last fall. One reviewer described the ecological thriller as “Watership Down with dolphins.” Caney also created an accompanying social media network (Facebook ‘Dolphin’s Way’) to support the book. He says a sequel is on the way.

Colleagues say that Caney has a gift for communications and an uncanny ability to digest dense technical subject matter and explain it in a way that everyone can understand. They also say that he is able to bring people together to find common ground and consensus. He is clearly putting both skills to good use in developing and selling PADI’s rebreather program while getting a buy-in from manufacturers on his rebreather concepts.

Here is what the man had to say.

DIVER: What was your first exposure to rebreather technology?

Mark Caney: The Dräger Atlantis was really my first in about 1995. They were semi-closed units of course. Soon after that, I had my first experience with an Inspiration (Ambient Pressure Diving Ltd.), which was a fully closed system. I think that was in ’96 or ’97. Martin Parker [Managing Director] took me for a dive off the South Coast (UK), and I went on from there.

DIVER: I remember there was a lot of excitement around the Dräger Atlantis, particularly because behind it was a large established company experienced at building rebreathers.

Mark Caney: Yeah, they were solidly built machines. The problem was if you followed the instructions and used the orifice sizes they said, it didn’t give you a lot of advantage. I mean, most of us could make a scuba tank last as long. So basically you had all this additional hassle for minimal extra advantage. In that respect I saw manual semi-closed units as being a fairly limited technology. They weren’t giving you a huge advantage over open-circuit, whereas a fully closed electronic unit can give you tremendously greater advantages.

DIVER: One of the conclusions of Rebreather Forum 2.0 was that semi-closed rebreathers might be more suitable for recreational divers (vs. technical divers) because it was much simpler technology and didn’t use pure oxygen. Of course Drager was aiming their rebreather squarely at the recreational market; the unit was not meant for tech divers.

Mark Caney: Which is a sensible way to do it if you’re a rebreather manufacturer and you want to make any money because you are only going to sell a small number of machines to technical divers, who want to take them into potentially extreme environments. Theoretically, you can sell a lot more units to recreational divers.

DIVER: So do you think that was the fundamental reason that the Atlantis never really took off: it was more expensive and complicated than open circuit, but really didn’t add much to a diver’s experience, and therefore it just didn’t really get any traction?

Mark Caney: I think that was a lot of it. It didn’t let you do a great deal more. But it was also ahead of the curve, because to my mind the technology didn’t have the three components necessary to make it successful. It’s the triangle of support concept that I presented at the Diving Equipment and Marketing Association (DEMA) show and other places. To be successful, the technology has to work. You must have training in place, and the technology needs to be supported when you travel; that is, you need the support infrastructure.

In those days it was hard to get nitrox, let alone high-pressure oxygen. You couldn’t get absorbent (used to remove the CO2 from the breathing loop) very readily. It was a hassle traveling with one of those things. It’s easier today. If somebody launched the Drager today they’d probably have more success. Of course, the new electronically controlled semi-closed machine that Hollis Gear and VR Technology Ltd. are planning to bring out will likely offer divers many more advantages.

DIVER: So is it fair to say that you and your colleagues at PADI started thinking about offering rebreather training to recreational divers as a result of the Atlantis?

Mark Caney: Yeah. I remember Drew Richardson, Karl Shreeves, James Morgan and myself taking an Atlantis training course, and subsequently we created a specialty program for the Dräger unit. They were fine with that but we never allowed fully closed units at that point.

Afterwards, it basically became my job to monitor the rebreather marketplace and let the company know when it seemed appropriate for us to join in. And I monitored for a long time saying, “no, not yet,” for many, many years. Along the way, I was trying to influence key parts of the industry to see that there could be a split between recreational and technical rebreathers.

DIVER: Is that when you began developing the concept of a “Type R” rebreather that presumably can be used safely by recreational divers, as distinct from the kind of rebreathers currently used by tekkies, the so-called Type T machines?

Mark Caney: That’s right. It was early to mid-2000s and I began to think out what features would be required in a recreational rebreather. My logic was that most of the existing machines on the market were complex and suitable only for technical divers. But then, you expect technical divers to be knowledgeable and disciplined, and be able work through steps required to diagnose and solve problems on their rebreathers. But those types of machines were not appropriate for a recreational diver. So we began analyzing incident cases to figure out what commonly went wrong during dives with rebreathers and what could be done about it. I thought if you could engineer out most of those common mistakes, then you’d have a machine that would more closely resemble open circuit gear.

DIVER: In terms of ease of use?

Mark Caney: Open circuit gear works well because it’s relatively idiot-proof. For example, if you don’t remember to turn on your cylinder and you jump in the water and try to breath, you get immediate biofeedback that something is wrong.

DIVER: So your idea was to spec out an ‘idiot-proof’ rebreather.

Mark Caney: Basically, yes. So what if you could have that capability built into the machine? If you jumped in the water and forgot to turn it on, either the machine would turn itself on or it was able to warn you in an unmistakable way that something was wrong. Or warn you if your oxygen is not turned on or the scrubber canister is not in place, or there is some other problem with the unit. If you could deal with most of the inevitable stupid mistakes in that way, the mistakes that you could predict divers are going to make, then you would start to have a machine that is appropriate for recreational divers.

DIVER: You created a list of 23 features that a ‘Type R’ rebreather should offer to be suitable for use by recreational divers, and to be acceptable for use in the PADI teaching system. Things like: automatically turns on if the user forgets, cannot be assembled incorrectly, won’t operate without the scrubber canister present or the gas cylinders turned off, has a built-in open circuit bailout valve and a mandatory pre-dive check list, etc. And likewise, there’s a set of features required for technical diving rebreathers, the ‘Type T’ machine.

Mark Caney: I came up with that terminology and we wrote a set of specs for both the Type R and Type T machines that could be taught under the PADI system.

DIVER: So your idea is that the R-machine will take care of users by not letting them do stupid things, and warn them if there’s a problem. And if something goes wrong – when something goes wrong – the diver throws the integrated bailout valve, goes to open circuit and aborts the dive.

Mark Caney: Exactly. And fortunately, around the time we were developing the spec, Poseidon Diving Systems, which had begun working on their MKVI rebreather for recreational divers, approached me. They were very interested in our viewpoint and our Type R and Type T concept, and ended up incorporating a lot of our thinking into their design.

DIVER: I spoke to the people at Poseidon, which licenses their technology from engineer, inventor and explorer Dr. Bill Stone, founder of Stone Aerospace Inc. Their MKVI ‘Discovery’ is the first and only R-machine on the market right now… correct? They have been available for about three years. Are there others in the works?

Mark Caney: Poseidon is the only one currently. However, we know that Ambient Pressure Diving Ltd. is going to launch one very soon that they say fits the Type R criteria. We expect that the Hollis electronic semi-closed unit when it’s launched will also meet the criteria, and I believe that Inner Space Systems, which makes the Megalodon, will also be coming out with a Type R unit.

DIVER: The Poseidon has been out in the field and has a track record, but what about new units coming out? Are there any concerns about the units getting enough field use before PADI instructors start training people on their use?

Mark Caney: This is one of the reasons we ask for nationally or internationally recognized third party testing, like CE (safety/compliance) testing, for these machines as part of both the Type R and Type T specs. We want manufacturers to say: here’s our machine, it does all of these things and it’s had third party testing. Serious manufacturers are not going to release a machine that is untested. So I’d be very confident if one of these manufacturers released a machine that had been tested.

DIVER: That seems like PADI is helping to raise the bar with regards to testing.

Mark Caney: Well, we don’t want to be in the business of saying what’s a good machine, or what’s a bad machine. That’s not our job. We’ve never done that in open circuit. We don’t want to do it in closed circuit. There are testing protocols out there and some vendors will choose to take advantage of them, and some vendors won’t. That’s their choice.

DIVER: But there’s more to the spec that just standardizing the product. Right? It’s about training.

Mark Caney: That’s right. There are really two parts to it. One is to make sure the machine will be appropriate for the capabilities of the diver. But the second part is to standardize the machines so that you could design a generic training program around them. Before Type R, the thinking was that you needed to create a separate course for each distinct rebreather on the market because they’re all different. But that wasn’t practical for the future.

DIVER: A generic training program? Meaning it wasn’t economic for the PADI system to create a course for every individual model of rebreather?

Mark Caney: Not just uneconomic, it is inefficient from a learning point of view. So that was part of my logic in designing the Type R and Type T specs. Since both types of machines will have the same standard features, it simplifies the process of building a standardized training program.

For example, our Rebreather Diver course, which is based on the Type R machine, will teach the student pretty much everything he or she needs to know about any Type R machine. It’s kind of like the story of the glass slipper and Cinderella; only certain feet are going to fit that shoe. So if the machine meets our criteria, then the course is going to give students what they need. Of course, there will be some unit specific issues like how to change the scrubber material on a particular machine. And the exact layout of the controls will be slightly different to each machine, but the instructor will provide that unit specific information.

DIVER: Rebreather training has been around in one form or the other for nearly 15 years now, and not all of it aimed at technical divers. There were recreational courses for the Dräger Atlantis, the Rebreather Association for International Divers offers recreational rebreather training, and so do some of the other training agencies like IANTD and TDI. What value do you think PADI brings to the party?

Mark Caney: I think technical rebreather training is getting more consistent. People have been doing it long enough that we’re starting to see consensus on many of the approaches among training agencies involved.

I think PADI’s biggest strength has been to come up with specific protocols on how recreational divers will be trained with rebreathers. That hadn’t really been codified anywhere near to the same degree. In fact, most organizations were only dabbling in it. At best, what they tended to do was just use the first chunk of their technical rebreather course if the diver wanted to learn to use it recreationally.

Regards our technical rebreather courses (on the Type T machines), we’re basically taking the PADI approach which is to codify everything and really give the instructor and the student the in-depth materials to provide them with the information they need, but we’re not doing anything radically different. The skills people will learn are generally the skills they can probably learn with other systems.

DIVER: It seems that PADI is assuming a new role in actively promoting recreational rebreather diving, which is very different, for example, than when the company began offering nitrox or tech training. In this case, you’re helping to create and drive a market that doesn’t exist yet.

Mark Caney: It happened as a sort of by-product really. It wasn’t our intention to necessarily drive the market as such, but the market was a lot more fluid and loose than the existing open circuit market and we felt uncomfortable with it as it was. It was not our position to say this is what the market had to do. Instead we are saying to manufacturers, these are the kind of parameters we’re prepared to work with, if you want to use your machines in the PADI system. Now it seems that quite a lot of companies are interested, and as a by-product therefore, I think we are influencing the market. For example, I am hearing manufacturers using the Type R and Type T terminology, so I suppose in that sense, yes, we are having some influence.

DIVER: As I’m sure you know, many people in the rebreather community are dead set against promoting and offering this technology to recreational divers for fear that it will wind up killing a lot of people. One of the arguments is that there is no real need for a rebreather if you’re doing 50 to 100-foot (15-30m) no-stop reef dives, but you’re adding significant risk to the dive. As one manufacturer put it to me, “if a bunch of doctors and dentists wind up dead it will hurt the whole industry.”

Mark Caney: Doesn’t that remind you of the arguments about nitrox when it first came out?

DIVER: No, not really. Even in the early days, few people died from diving nitrox. Granted, there were some deaths resulting from people switching to the wrong mix at depth and or people incorrectly labeling cylinders. However, these deaths seemed easily preventable with some simple procedures. Conversely, rebreathers seem like a whole other animal.

Mark Caney: I would say it’s a valid argument to consider whether the risks of rebreather diving are worth the rewards. But if you extrapolate something like that to it’s extreme, you could raise the same point about diving as a whole. You can snorkel and see quite a lot of stuff. Yet we know there are dangers inherent in putting a regulator in your mouth and breathing compressed gas underwater. Is it worth the added risk? So it really depends how far down that continuum you are prepared to go.

For part two of this interview, click here.