Rediscovering Divers Paradise

After visiting Bonaire for over twenty-five years, one author hadn’t expected to be returning as a father…

Words and Photography by Andrew Jalbert

In the early 1990s, armed with a recent degree in anthropology and a recreational scuba instructor rating, I set to work chasing the adventure I’d been craving since childhood. I managed to find employment as a low-level field archaeologist and was training divers on the weekends, desperately hoping that either career would lead to a life filled with international travel, exploration, and exhilarating experiences.

In retrospect, I was a bit optimistic about the former vocation: it led to such exotic locations as Des Moines, East St. Louis, Milwaukee, and Sioux Falls—arguably not the caliber of expedition worthy of note on Edmund Hillary’s curriculum vitae. It was my involvement in scuba that ultimately proved a bit closer to what I had been looking for.

I begged my way into a position as a part-time travel guide for a local dive shop, leading groups of scuba divers to the Caribbean. I was terribly underqualified for a number of reasons, including the rather troubling fact that I had never actually been to the Caribbean. It didn’t pay much, but the trade-off for the low salary was worth it: pages of colourful stamps in my passport and a regular dose of new experiences that sparked my interest in writing and photography.

My first trip as a dive leader was to the island of Bonaire. Set roughly fifty miles (80km) off the coast of Venezuela, Bonaire is one of three islands in the Leeward Antilles referred to as the ABCs. This memorable acronym is representative of the individual island names within the chain: Aruba, marking the western boundary, Bonaire to the east, and CuraÇao between the two. With the exception of sailors, wind surfers, or scuba divers, the majority of people I talked to knew little, if anything, about the ABC islands. Aruba is familiar in name to most, but I suspect this can be attributed largely to the Beach Boys, who, with a ridiculously enticing “Come on pretty mama” lyrically invited us to the island via other, more well known destinations like Jamaica, Bermuda, and the Bahamas.

In fact, Bonaire scarcely resembles Jamaica or the Bahamas at all. For starters, it’s dry. Bonaire averages around twenty inches (50cm) of rain every year, a mere spritzing compared to many other tropical destinations. With its cactus-lined roads, darting lizards, and blazing sun, its interior feels more like the American Southwest than the lush, palm-covered environment that Caribbean islands so readily bring to mind. It wasn’t the island’s interior that brought so many of us there, however; it was what could be found just off its shores.

Divers’ Paradise

Driven by a tourism economy based largely on scuba, Bonaire had earned the title it boasted on its license plates: ‘Divers Paradise’. From the island’s protected nearshore reef system and calm seas to its first-rate dive facilities, Bonaire had become one of the world’s premiere destinations for scuba enthusiasts. I pored through every book and article I could find about Bonaire (a time-consuming task in the years before the internet) in the unnerving and very probable event that someone in my group had the gall to ask their guide a question about the island. Miraculously, the week passed without incident, and I returned to Wisconsin deeply tanned, a bit more confident, and itching to travel again.

Other than a couple of jaunts to the Florida Keys, I’d spent little time in warmer climates prior to that first trip to Bonaire. Like so many of us who got our start in the northern latitudes, my diving teeth were cut along murky lake bottoms, in deep frigid quarries, and local rivers. When we wanted a taste of bigger water, we loaded up our gear and drove to Lake Superior to explore one of the countless shipwrecks scattered across the chilly lakebed. I loved these freshwater environments, and still do. Nonetheless, that first experience of exploring the reefs fringing Bonaire was impactful. It was there that I first saw the staggering diversity of a coral ecosystem, where I learned about its fragility, and perhaps most importantly, where I came to understand how cooperative conservation efforts designed to preserve these environments could lead to a successful ecotourism industry.

Bonaire is where I was first exposed to iconic marine conservationists: people like Don Stewart, the colourful captain who’d sailed into Kralendijk 30 years prior and who was instrumental in building both the island’s dive industry and the Marine Park; and Women Divers Hall of Fame member Dee Scarr, the photojournalist who created the Touch the Sea program, led the sponge reattachment project beneath Town Pier, and who was the second person behind Jacques-Yves Cousteau to be awarded the PADI/SeaSpace Environmental Awareness Award. That trip to Bonaire so long ago was not simply educational. It was inspiring. Everyone, it seemed, was working together to protect this place: government, individuals, foundations, and dive operations.

This was more than just a noble cause, however; it was good business. The reef is Bonaire’s gem, one of the main draws to the island, and nearly everyone has a stake in it to some degree. It’s made up of over fifty species of coral and starts just a few hundred feet (90m) from shore in most places, extending nearly a thousand feet (305m) out toward open water. This entire area was designated as the Bonaire National Marine Park in 1979 and has been protected accordingly ever since. Spearfishing is prohibited and there is no collecting allowed (of anything, dead or alive, including seashells or broken pieces of coral), no use of gloves, and no disturbing the turtles, their nests, or their eggs. Even chemical glow sticks for night diving are forbidden. Other regulations apply to anchoring, fishing, shoreline structures, sand extraction, tree cutting, and campfires, all in place to keep the environment pristine. And it’s been working for more than 40 years.

But the draw to Bonaire goes beyond the protected reef system itself: it’s also the freedom with which it can be explored. The island’s leeward coast is lined with beautiful, healthy dive sites so close to shore you can swim right to them if you don’t particularly feel like catching a boat. You simply pull off the road by one of the yellow-painted rocks marking the site location, gear up, and wade into the warm water or step off the dock. Swim a couple hundred feet and you’ll come to the head of the coral drop-offs. There are spare air tanks in the bed of your truck and not a thing on your schedule. If you don’t feel like diving at 8:00, you sleep in, lounge around drinking coffee, then set off at 10:00. If you don’t want to visit a particular section of the reef, you simply drive down the road to another. If you suddenly get the

urge to dive again late in the day, that’s exactly what you do. It’s complete freedom. And, as I learned after the birth of our son Luc in 2012, if you happen to be traveling with a young child who has his own schedule to work around, this freedom becomes priceless.

It’s personal

I’d been visiting Bonaire at least once a year since the early 1990s in a variety of capacitates: as a scuba instructor, a dive guide, a sun-starved vacationer, and a writer/photographer. Becoming a new father later in life, however, left me wondering if these regular trips would become a thing of the past. I worried that my connection to this island could be severed as more pressing domestic responsibilities crowded my life. One thing seemed perfectly clear to my wife Becky and me: we either gave up the things we loved to do, or we found a way to bring our child with us. So, against all reason or common sense, we jammed diapers, bottles, and burp cloths into our gear bags, checked a stroller at the boarding gate, and struck off for Bonaire with Luc before he could even walk.

Our reasons for taking that first trip with Luc were purely selfish. We simply wanted to recapture some of our ‘childless’ identities and diving was a big part of them. Yet as the week progressed, something unexpected started to happen. My role as a father had led to not only a new, vastly broadened perspective, but also a heightened concern for the underwater environments I’d been documenting for decades. The threats to our oceans, from atmospheric warming to pollution, are daunting and the decline of this environment will fall heavily on my son’s shoulders. During that week, all of this suddenly became very personal. And in that, our trip became less about Becky and me and more about Luc.

My desire to show and teach our son about these places grew as he did, and my concerns about not returning to Bonaire have long since vanished. With Luc joyfully in tow, my wife and I have been back every year since his birth eight years ago. Like the first trip 25 years ago, being on Bonaire with our son has been powerful. I want Luc to be able to experience the underwater world firsthand if he chooses and not just through his dad’s photographs.

Yet by the time Luc is my age, the coral I’ve been exploring in recent years (along Bonaire and elsewhere) might not be around, at least not as it is today. The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) recently published a global assessment of the 29 World Heritage reefs (reefs recognized for their “unique and global importance and for being part of our common heritage of humanity”.) The conclusion was rather grim: unless ocean warming is slowed, at least 25 of the 29 World Heritage reef areas will experience “twice per decade severe bleaching events by 2040—a frequency that will rapidly kill most corals present and prevent successful reproduction necessary for recovery of corals.” And even more troubling: “The analysis predicts that all 29 coral-containing World Heritage sites might cease to exist as functioning coral reef ecosystems by the end of this century if CO2 emissions are not drastically reduced.”

Awareness

Both atmospheric warming and pollution are almost inconceivably large-scale matters, and solving them is a long, slow process steeped in politics, industry, economics, environmental science, and an awareness on our collective part as consumers. It’s the more directly preventable threats to the ecosystem that Bonaire has successfully taken on. Human interaction with the reef, if done irresponsibly, can have devastating effects. At first glance, many of the conservation guidelines in place on Bonaire may seem a bit nitpicky but they exist for good reason. It’s hard to imagine what this environment might look like if its use had gone unregulated over the last 35 years: thousands of visitors free to break off and collect coral (an unfortunate recreation in other parts of the world), spearfish, drop anchors wherever they please, flush waste waters from their boats, or dive untrained, crashing into the coral dive after dive. The results, as evidenced elsewhere around the globe, could be tragic. Bonaire is a place of lessons: to both learn and pass along. And over the past few years, it’s become a living classroom for my son. He doesn’t simply know about the rules here, he understands why the rules exist.

Luc’s introduction to the ocean has been slow and methodical. It began in the pool before he could walk and progressed steadily over the following years. By the time he was six years old, we were snorkeling together over shallow sections of Bonaire’s reef, identifying fish and coral species. And on a rather momentous day, just weeks before the island would be shut down in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Luc sank beneath the waterline of the resort pool while breathing from a regulator. But there was more to teaching my son about responsible diving than skills alone: later that same day, we also spent time on the southeast coast of Bonaire picking up plastic that had washed ashore. He may not have enjoyed it as much as being in the water, but even at such a young age, he understood why we were doing it. Perhaps most importantly, he has history here now, a connection.

And for a boy like Luc, the path from connecting to caring is a

short one.

The time will come when Luc will start asking more questions, something I look forward to and dread at the same time. They’ll be a child’s questions, predictably steeped in simplicity, and with such remarkable sensibility as to fluster the adult attempting to explain their complex answers.

Why do we keep polluting if it hurts the ocean? The social, political, and geographical explanations will come at a later time. For now, I’ll teach him about the ocean and its inhabitants—show them to him the best way I know how. And in the process, I’ll get to rediscover this island through his eyes.

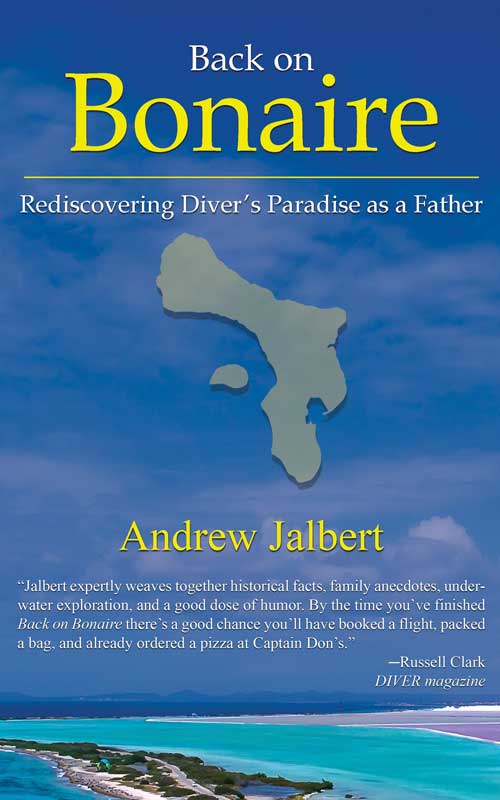

About the book:

Back on Bonaire is the story of stitching together two very different lives: one of airports, scuba tanks, article assignments and underwater cameras; the other of car seats, kindergarten, skinned knees and the boundless curiosity of a child. Andrew Jalbert merges both worlds in an enjoyable, funny and at times touching account of introducing his son to his beloved Bonaire. Along the way the reader gets a look at the island’s cultural and natural history, some of its people and the importance of preserving the ecology of Bonaire—for his son and future generations.

Paperback and Kindle versions avilable from Amazon. Apple Books, Barnes & Noble, and Kobo.com

Andrew Jalbert is an award-winning photographer, writer, and doting father. Throughout his twenty-five years as an archaeologist, scuba instructor and dive guide he has traveled extensively, publishing work on prehistoric sites, shipwrecks, travel, dive safety, and conservation. Jalbert lives in Wisconsin with his wife Becky and their son Luc.

Leave a Comment