Shake Up Your Environment

By Divers Alert Network

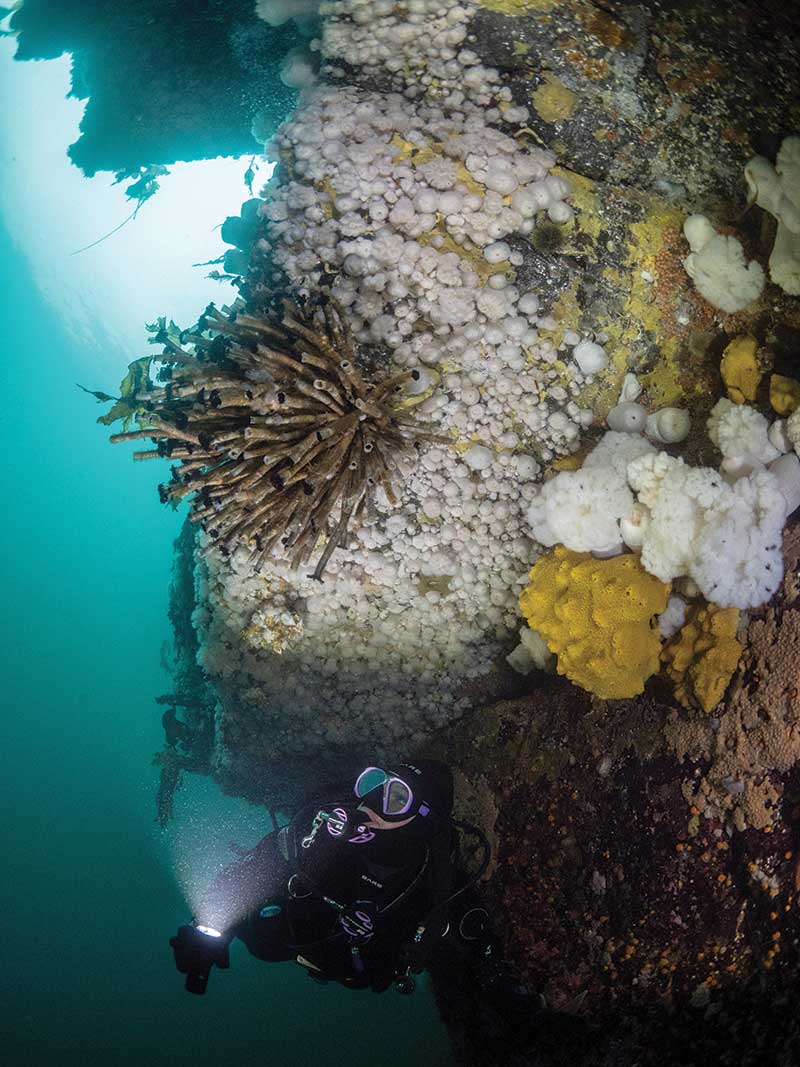

another one”. Photo: Russell Clark

Dive sites are never constant. From currents to water temperature to depth, environmental variables can offer unique challenges and adventures. But before you embark on a new dive experience, make sure you have the skills you need and are well prepared for the conditions.

Currents

There are a few different ways to approach diving in currents. One is to start out swimming against the current and then return with it. Physical effort and breathing gas consumption will be elevated as you swim against the current, but you’ll use much less energy as you return to the entry/exit point. Divers should avoid diving in currents greater than one knot without proper training and experience. Another approach, drift diving, enables a diver to start at Point A and calmly voyage to Point B. Many drift dives are relaxing endeavours, with the current doing most of the work.

Prior to diving in current, divers should be fit enough to swim against a current if necessary and familiar with different finning techniques. Dive leaders should provide site-specific information about the current as part of their predive briefing. Certain equipment, such as a surface marker buoy (SMB), can prove helpful when you need to mark your location so boaters (and perhaps your dive operator) know where you are. It’s easy to get separated during dives in current, so it’s wise for each diver to carry their own SMB when diving in current.

Try to avoid getting into situations that require you to fight against currents, and don’t panic if you get swept away during the dive. Sometimes moving a few feet laterally can diminish the effects of a current.

Temperature

When diving in water that’s colder than you’re used to, you might need a thicker wetsuit, a neoprene vest, a hood, and/or gloves. If the water is very cold, you may need a drysuit—and the special training required to use it safely.

Your body will burn more calories to stay warm in colder water, so be sure to fuel up with nutrient-dense snacks before and between dives. When you’re ready to try diving in colder water, don’t head straight to Antarctica—shoot for water around 55°F (13°C) first. If you’re used to the tropics, you might be surprised by the different marine life you’ll see in temperate water. An entirely new ecosystem awaits.

Depth

As you dive deeper, keep in mind your gas consumption will increase. While the volume of your breaths won’t change much, the gas you breathe will be denser. Keep an extra close eye on your gas supply, as you’ll deplete it much faster than when diving in shallower water.

Even if your gas supply is sufficient to stay at depth for a while, you might find your time limited instead by your no-decompression limit (NDL). As you know, exceeding your NDL elevates your risk of decompression sickness, so it’s important to also pay close attention to your watch or computer so you’ll know when it’s time to start your ascent.

Because there’s less light at depth, you’ll want a dive light on deeper dives. You may also need additional exposure protection for the colder temperature.

Visibility

Low visibility is the result of particulate matter such as algae or silt in the water column. Visibility varies from site to site and day to day (or even hour to hour). While low visibility is generally regarded as suboptimal for diving, the challenge of it can help divers become more comfortable in less-than-ideal conditions. Another benefit of low-visibility diving is that it can lead divers to focus on smaller details they might otherwise overlook.

A major safety concern with low vis is buddy separation. Tethers, dive lights, or attachable beacons can help make buddies visible to one another. And because it’s easy to get disoriented or lost, a compass can be very helpful.

Darkness

Diving at night is very different than diving in the morning or afternoon. The lack of daylight makes for a fascinatingly distinct experience. And the nocturnal creatures that emerge to feed or mate can be quite unusual.

Before any night dive, make sure you’re familiar with the area or are diving with someone who is. If you’re entering from the shore, mark your entry point with lights.

Visibility will be limited, and you’ll need some extra equipment to ensure safety. Beacons and lights are a must, and you’ll want a backup light in case your primary fails. Also have your compass handy.

Adapt change slowly

When you face changes in your dive environment, do so intentionally. To the extent you’re able to do so, change only one variable at a time, and make sure you’re comfortable enough before altering another one. Certain environments may require additional training.

With a few extra preparations, you can have a completely different and rewarding dive experience. You might even discover a new favourite way to dive!

For more safety information on safe diving practices visit: www.dan.org

Leave a Comment