The Dark Side of Wakatobi

Words by Joseph Frey

Nighttime fluoro diving offers an entirely new perspective to the stunningly beautiful and pristine reefs of the famous Coral Triangle

With the planet’s coral reefs dying off due to human activities and few healthy reefs left to dive on in the Caribbean region, divers have to travel further afield to find healthy coral ecosystems. So based on a friend’s recommendation, I decided to trek half way around the world to Wakatobi Dive Resort in central Indonesia, where the coral reefs are healthy and the surrounding environs serene.

Located off South East Sulawesi in the remote Tukang Besi island chain, Wakatobi is a mere 2½ hour flight from Bali on the resort’s chartered plane. It’s been an enjoyable flight as Wakatobi’s concierge staff of thirty in Bali makes the transfer to this flight seamless, plus the view of the region’s coral reefs from the air is stunning.

Our group of approximately thirty divers hail from North America, Europe, and Australia. We’re an adventurous group of travellers with diverse backgrounds. A couple hours after arriving, as I’m suiting up for our first dive, I start chatting with Esther Kiener who comes from Stansstad, Switzerland. Esther tells me that this is her second stay at Wakatobi and she now only dives in Indonesia as pristine coral can still be found here. Esther’s comments are reinforced by Barbara Fox, an underwater photographer from Seattle. She tells me that this is her fourth trip to Wakatobi. The coral reefs here are extremely healthy, providing her with the rich array of corals that she needs for her photography.

The corals weren’t always in such prime condition. Just a few decades ago they had been devastated by local fishermen using dynamite, cyanide, and large nets to fish on these reefs. It was with the arrival of German-Swiss entrepreneur Lorenz Mader that things started to change. He recounts, “My vision was to create a new type of dive resort, far away from tourism hot spots, that would operate in an ecologically responsible manner and bring tangible good to the local community. In 1994 I began to search Indonesia’s Wallacea region, which is widely known as having the world’s greatest marine biodiversity. This eventually brought me to the Tukang Besi islands.”

In the Beginning

After months of trekking through the remote islands and exploring reefs on local fishermen’s boats, Mader came upon a small island corner known to the locals as Onemobaa—the long, white beach. It was there, where a palm-fringed beach met a magnificent reef that he knew he’d found the perfect spot.

There were numerous challenges in creating what would become a world-class resort in an area so remote: the local people had not seen Europeans since the Dutch left the country, and electricity and running water were still unavailable. But equally important to Mader was establishing a business model that would provide protection for one of the world’s most pristine and beautiful ecosystems, while at the same time developing benefits for local economic welfare and social responsibility. Construction began in 1995 with the first building, the Longhouse, which had a capacity of just twelve guests. Now Wakatobi has 24 bungalows and four villas accommodating up to 70 guests.

“In 1997, we created the Collaborative Reef Conservation Program. This was the first program of its kind. It provided lease payments made directly to local fishermen and villagers to halt destructive fishing practices and encourage local participation in creating a marine reserve,” says Mader. This reserve now stretches across twelve and a half miles (20km) of prime coral reef habitat. The program was designed to show the local community that besides fishing on the reefs, it is possible to generate income from tourists who are just looking at fish and corals. This business model inspired the villagers to take an active role in protecting the marine ecosystem, and it has transformed the surrounding community into stewards of the reefs and demonstrated the economic value of protecting this unique ecosystem. Because this program is funded by a portion of resort revenue, all guests of Wakatobi Dive Resort become part of the solution.

“We protect what we love and understand,” Mader says. “I never intended―or wished―to be a hotelier. Sharing the beauty of coral reefs through dive tourism provided a means to share my love of the ocean, while also creating methods for protecting the ecosystem. Establishing what would grow to become a world-class resort property was actually just a means to this end.”

Ecologically Responsible

I’m immediately struck by the healthy coral as we do our checkout dive on the resort’s house reef. House reefs, based on my experience, are normally in poor condition from too many snorkelers and scuba divers diving on them. Corals are additionally stressed by the frequent destruction of the natural shoreline required to accommodate hotels, and/or from pollution generated by the hotels. But not here in Wakatobi; it is literally the best house reef I’ve seen anywhere in the world. Part of the reason is that Wakatobi’s sewage filtration system, using a natural filtration process, prevents coral-killing nutrients from seeping through the ground into the sea.

Wakatobi’s reefs are pristine and lush with a huge diversity of soft and hard corals, sponges, sea fans, fish, and other marine life. The surrounding waters are crystal clear, providing clear line of sight of up to 100 feet (30m) or more over the walls, allowing snorkelers and scuba divers to spot numerous sea turtles, schools of larger fish such as blueline fusiliers, barracuda, grouper, tuna, porcupine fish, bumphead parrotfish, along with amazingly diverse species of reef fish.

The resort’s almost four-dozen dive sites are beautiful and each has special features. The reefs along the steep underwater walls provide the most diverse corals and aquatic life. “One of my favourite sites was Batfish Wall, a beautiful shallow reef with a dramatic 65 foot [20m] drop. I was floating along with huge schools of pyramid butterfly fish, clownfish, triggerfish, puffer and porcupine fish, volitan lionfish, yellowtail coris, emperor angelfish, and so many species of butterfly fish that I couldn’t remember them all. And the Pastel site was another memorable site with an amazing underwater garden of pink, peach, tan, yellow, and orange corals, sponges, and fans,” says Carolyn Brehm of Washington, D.C. who along with her husband Richard was staying in the neighbouring beach-front bungalow.

“I loved the night dive at the Zoo site”, said Carolyn. “It was the opportunity to see the reef at night and how the reef fish hide in the holes and crevices while the lobster, shrimp, and other critters are active. We watched an octopus turn from purple to beige to green as it moved around the reef and saw a cuttlefish close up”.

Night diving at Wakatobi is magical; not only do the reefs come alive, but upon returning to the surface I’m captivated by the star-filled heavens above. As I swim back to our dive boat I stop and slowly turn 360 degrees and take in the vista of the dark outlines of islands in the distance and not a single electric light in sight. It’s serene. I’m feeling at peace here. This alone made the trip halfway around the world from Toronto worthwhile.

Night-time Fantasy

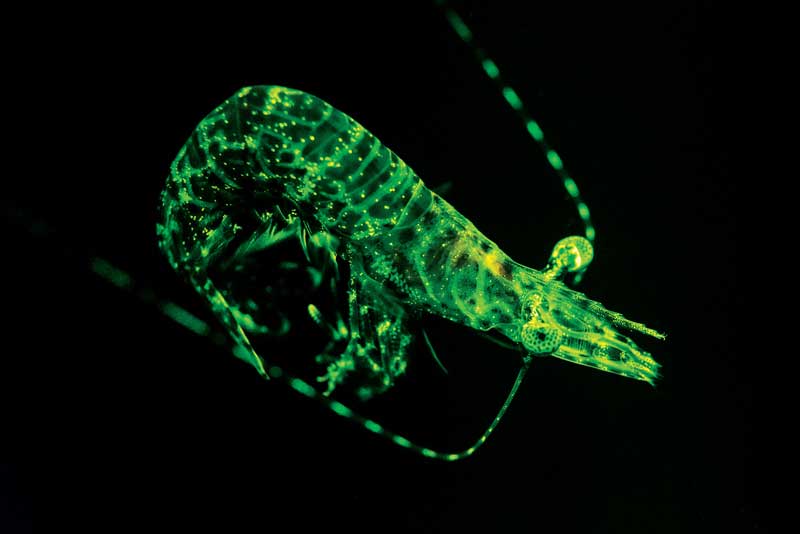

There’s an additional dimension to night diving that I’ve never experienced before, and why am I not surprised that I’m introduced to it here at Wakatobi? Fluorescent diving, also known as flouro diving. Not to get too technical, fluorescence diving occurs because certain types of minerals and marine flora and fauna absorb high energy light during the day and re-emit the light at lower energy levels at night. In order to see the night-time flouro light display, I have to strap a yellow visor over my dive mask and dive with a blue light-emitting underwater flashlight. As part of their concierge service Wakatobi provides both the yellow visor and blue light underwater flashlights, unlike most other dive operators around the world who don’t. To top it off South East Asia has the best flouro diving on the planet, with Wakatobi’s flouro dives being second to none.

Diving with me on the flouro dive are Erica Watson, of Chicago, and Rich Polgar, of Princeton, New Jersey. As our dive boat sails towards the setting evening sun Erica mentions, “I first heard of flouro diving through Rich, he was adamant that we try this type of diving and that Wakatobi was the place to do it”. As the boat reaches the Dunioa Baru dive site we slip beneath the calm surface, slowly descending to the reef below. Below us an octopus skims along the top of the reef, suddenly darting below a large potato coral. We switch our normal lights off and our blue lights on in order to begin our search in flouro mode. Immediately the coral glows, parts of it glowing green, parts orange, and yet other parts red. As the light topside dwindles, the colours become more vibrant with gobies showing on the coral, their skeletons glowing red through their skin. Lizard fish are easily seen hiding in the sand, with either their whole body visible, or the tell-tale green glow of their head vibrant against the darkness of the sand. Next we come upon a mantis shrimp, glowing a bright gold, like a golden coin in the sand. Interestingly, the very next thing we come across two feet (60cm) away is another mantis shrimp, but this one does not glow at all. “It was the best experience to be able to see the two so soon after one another to understand and remember that not all creatures of the same species will fluoresce”, remarks Erica.

So many creatures glow in a variety of colours that it feels like a whole new world to explore, although care is still needed as many venomous fish and creatures, like lionfish, that are easily visible during the day and normal night diving are not visible at all with flouro gear. During the flouro dive I momentarily switch off the blue lights, reposition the yellow visor above my eyes and turn on my normal light to see what is in front of me and to my surprise most types of corals don’t fluoresce. What appeared to be a dive site of only coral heads consisting of fluoresced brain coral turns out to be part of a wall of potato and leather corals and within six feet (2m) of me are three spotfin lionfish. What a contrast from normal night diving! Twice more during the flouro dive do I go from blue lights to normal lights to check out what is actually around me. It’s fascinating to contrast the two.

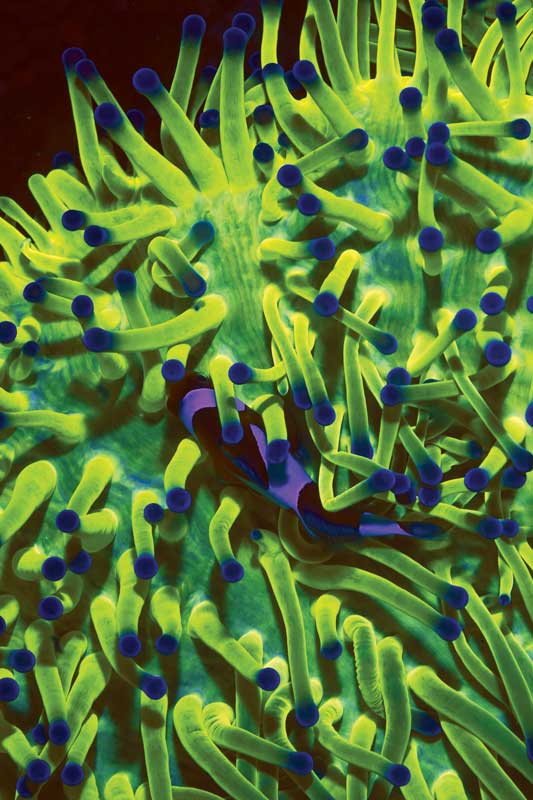

We see many other creatures that night, including anemones that glow bright green with blue tips. It’s such an odd sight to have the anemone fish be the secondary item versus the main photographic subject. Sea squirts, normally green, fluoresce a brilliant blue, while brownish-purplish stonefish fluoresce a bright red, and the fluoresced bones of whip coral gobies really stand out. “I cannot say it is easy to take images underwater at night, but for me the darkness and florescence simplifies some of the complications in finding the creatures underwater and isolating them from the backgrounds that can during the day be too distracting,” says Erica after the dive.

Memorable

It is a leisurely week of diving with most of us diving three times a day, while others, mainly the younger divers, get wet up to five times per day. Leisurely evening dives on the magnificent house reef make fourth and fifth dives possible. As the week slowly meanders on with glorious sunny blue skies and afternoon January temperatures in the high 80s/low 90s Fahrenheit (low 30s Celsius), all moderated with a slight, steady breeze keeping the humidity comfortable, it couldn’t be more perfect. On the last evening I chat with Carolyn, who reminisces about her highlights of the preceding week. “I saw two octopuses mating, squid, a giant moray in a hole, and a yellow margin eel poking its head out of a sponge about eight inches [20cm] from my nose. I was captivated by the blue spotted stingrays hiding in the sandy bottom, along with mandarin peacock shrimp, banded krait sea snakes, and several mammoth lobsters. Over the course of the week I spotted close to ten sea turtles, a mix of green and hawksbills. Wakatobi’s remote location is part of its magic,” comments Carolyn. “It is a place that we will return to and share our discovery with friends. It was a most memorable week.”

For more visit: www.wakatobi.com

Leave a Comment