Zalinski Less Threatening

Tonnes of fuel oil were recovered from the aging wreck but the Coast Guard says it will monitor the remote site for leakage

Text by Robert Osborne

Grenville Channel is the very epitome of west coast beauty. Rugged, heavily forested mountain slopes plunge precipitously into the deep, dark water of the sound; pristine beauty that has not gone unnoticed. Just 60 or so miles (100km) south of Prince Rupert, the wilderness passage is a regular summertime route for cruise ships operating out of Vancouver on their way to and from Alaska. And yet for more than half a century this picture of nature’s perfection could have been unimaginably defiled almost instantly. For beneath the still waters of Grenville Channel there’s an environmental time bomb—a sunken wreck once fueled by tonnes of bunker oil that could have burst free of its holding tanks at any moment. What’s surprising about this ticking time bomb is that the government, including the Canadian Coast Guard, knew about it for more than a decade and did nothing.

Though a cliché, it’s a matter of record that this story begins on a dark and stormy night. A U.S. Army transport ship, the 2,600 tonne Brigadier General M.G. Zalinski was making her way up the British Columbia coast in September of 1946, loaded with a cargo of military supplies, including bombs and other ammunition, and lumber. Bound for Whittier, Alaska, the freighter was also old and tired. Launched in 1919 as the Lake Frohna she’d worked the Great Lakes for years, becoming the Ace in 1924 under the new ownership of the Ace Steamship Company. But when the Second World War broke out her role changed. In 1941 she was purchased by the U.S. Army as a transport vessel, renamed for a noteworthy military man and moved out to the Pacific coast where she spent the war ferrying supplies from Seattle to troops in Alaska on a kind of cargo milk run with little risk of running into enemy submarines.

Post War Prang

Ironically, it was weeks after the Japanese surrender and the end of the war that the Zalinski met her own end. September 26 had been a squally day as the vessel steamed north under command of Captain Joseph Zardis and a crew of 48 men, all likely relieved to enter the relatively sheltered water of British Columbia’s Inside Passage. But as darkness fell the weather began to worsen. Winds started blowing out of the southeast at 45 miles (70km) per hour. Visibility dropped. Crewmember Bernard Boersema’s later account published in the Vancouver Sun said, “Driving rain made it so black we couldn’t even see the bow.” Despite the foul weather, Captain Zardis continued to push his ship at a good clip and, inexplicably, decided in the early hours of the morning to go below for a little shut-eye. Even more perplexing is that some accounts suggest the

Zalinski was without working radar. It was a recipe for disaster, which struck at 3:59 a.m. on the 27th when the ship ploughed into rocks just off Pitt Island, a collision so hard the ship bounced back into the middle, deeper part of the channel.

According to Fred Rogers, author of More Shipwrecks of British Columbia, the mate immediately ordered the crew to survey the holds for damage. They found water rising fast. “Force of the collision broke numbers one and two holds clear open—a tear of about 40 feet (12m),” crewmember Boersema recalled. There wasn’t even time to collect personal effects. “There was already about seven feet (2m) of water in number two hold and more rushing in like fury. I knew then we were sinking,” he said.

Zardis gave the abandon ship order; a distress call was made and picked up by the vessel Sally N. but the crew had to take to their lifeboats before its arrival. The Zalinski sank 20 minutes after she struck the rocks and other than the Captain’s report filed in Prince Rupert on October 11, the old coastal freighter slipped out of the collective memory.

Oil and Ammo

Forgotten, that is, until September of 2003 when reports of oil slicks on the pristine waters of Grenville Channel surfaced. The Coast Guard ship Tanu investigated, reporting they “discovered no obvious source of the pollution.” But they did suspect a wreck, and archival research turned up the Zalinski story.

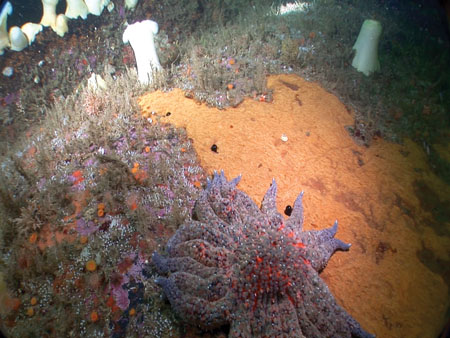

The Coast Guard returned to Grenville Channel in October with a remotely operated vehicle that located a large unidentified and overturned vessel resting at about 100 feet (30m). A month later divers completed a more comprehensive survey and applied some patches on the hull where oil was found to be leaking through corroded rivet holes. At the end of the job they still had not been able to positively identify the ship.

Despite the patches, the wreck was leaking again by February of 2004. The Coast Guard returned and plugged holes for a second time. By now a study of their findings, measurements of the vessel at 260 feet (80m), and also inventory of some cargo, led them to believe she was the General Zalinski. That was the good news; the bad was that they now knew what she was carrying: at least a dozen 500-pound bombs were in the cargo inventory and cases of .30 and .50 caliber rounds. Worst of all they knew she was holding a lot of bunker oil in fuel tanks capable of holding 700 tons (150,000 gallons). Together, these facts presented a potential nightmare scenario for the Canadian Coast Guard, about which little, if anything, was done for nearly a decade.

The Zalinski was a bit of a Gordian knot. She posed a problem. In a 2005 report authorities said, “It will begin to leak oil again in the near future, posing an imminent pollution threat.” They just didn’t seem to be able to act definitively to solve the problem. So for nearly nine years they did little more than study it, write reports, conduct meetings, make suggestions and then study it again.

At one point in this curious history the Coast Guard tried to pass the buck by handing the whole job over to another government department, the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan, but were unsuccessful because that department had insufficient resources to take care of the problem. Several private companies were asked to submit bids to take care of both the oil and the unexploded ordinance. A large volume of Coast Guard email correspondence ensued to consider what the next steps should be. In fact, to keep track of who was involved in this never-ending discussion someone eventually had to make a flow chart.

But Coast Guard Western Region Assistant Commissioner, Roger Girouard, says it wasn’t indecision at all, that it all came down to simple cost benefit analysis. “She wasn’t causing that much of a mess,” he said. Add to this the fact that the Coast Guard didn’t have $50 million dollars in its operating budget to take care of the job, and no one else in the government was rushing forward with the funds. So it was decided to leave well enough alone, as the saying goes.

Patchwork Problem

In the summer of 2012 divers were still finding oil leaking from the wreck. Brian Nadwidny and his fellow divers, John and Cathy McCuaig, from Calgary, who regularly charter a boat to travel up the west coast, diving favorite spots along the way, had explored the Zalinski on several occasions. In June of 2012 Nadwidny said, “Oil is still coming out through the rivets.” He believed the Coast Guard might have done some additional patching. “We found new patchwork near the bow,” he said. “It was a material that looked like silly putty.” On that occasion Nadwidney took pictures of the leaks and the 500-pound bombs scattered across the bottom.

Divers weren’t the only ones who noticed that the Zalinski continued to be a problem. The area is the traditional home of the Gitga’at First Nation. They claimed the oil spilling from the wreck was contaminating the marine life – a source of their food – in the local waters. Hereditary Chief Johnny Clifton wrote to Fisheries and Oceans spelling out the problem. He said the oil leak was “…likely to affect our ability to practice traditional harvest activities and damage important habitats.” He noted there were several salmon-bearing rivers threatened and that “other marine resources in the area…may also have become contaminated and unfit for human consumption.” In 2007 Gitga’at Chief Bob Hill sounded frustrated when answering questions about the problem. Describing the outcome of tests on shellfish beds his people harvest from, he said, “Thirteen sites had been tested for hydrocarbons and five had come up positive for traces of diesel.” Hill believed that the Coast Guard just wanted the problem to go away. He says they “would like to leave it alone, that’s what they’ve indicated.” What Hill and his people wanted to see was the vessel pumped dry of all oil, the problem solved once and for all.

Finally in the fall of 2013 the Coast Guard took action. Girouard says, “We hoped the patches would hold” but “the trend line was on the uptick.” The underwater salvage job was put out to tender, the successful bidder was chosen and the whole operation moved north to get the job done.

Salvage Complete?

The salvage was both easier and more difficult than the Coast Guard had anticipated. More difficult because the standard method of retrieving oil from a wreck is called ‘hot tapping’, wherein two valves are cut into the hull, one for injecting pressurized hot water, the other for attachment of a large vacuum pump to evacuate the oil loosened up by the hot water. Drawn to the surface the oil is then held in tanks for later disposal. But the Zalinski was too fragile to pressurize so all the salvagers could do was try to gently heat the oil and draw it to the surface and this worked but the effort may have been a little late. About 43 tons of oil was recovered. Had the rest of the oil leaked out over the years? There’s no conclusive answer to the question.

Of the ordnance in her cargo, Girouard said, the Department of National Defense advised it by left alone. The cleanup was expected to take months but took only a few weeks. The much feared break up of the wreck and associated oil spill was avoided.

A job finally done, an environmental disaster averted. But some critics see the recent action in a somewhat more cynical light. They question the motivation of the Coast Guard acting at this late date. It may have something to do with geography. Grenville Channel isn’t that far from site of the controversial Northern Gateway Pipeline terminus at Kitimat. Since Grenville Channel is one of the super tanker routes for transporting oil southwards, imagine the public outcry if the Zalinski had spilled its comparatively small quantity of fuel oil. And imagine the uphill battle for Northern Gateway thereafter. So was the Zalinski a convenient cleanup to avoid a potential public relations nightmare?

Girouard denies the allegation. He says it’s not the first time he’s heard this and that the Coast Guard was motivated solely by the need to finally clean up the problem.

Political motives behind the cleanup, or not, the problem has been taken care of and that’s noteworthy considered in a global perspective. The Zalinski is only one of 8,500 sunken wrecks around the world on the verge of spilling their cargo into the oceans. And that list only covers ships of a certain size that pose “a significant oil pollution risk,” according to a 2005 report completed for an International Oil Spill Conference. Recently the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) completed a study of wrecks in U.S. waters that needed to be attended to urgently—they found 87. Canada has not completed a similar inventory.

If only a fraction of these wrecks start breaking up they could cause environmental disaster on an unprecedented scale. Estimates put the oil held collectively by the 8,500 wrecks at six billion gallons—28 times more oil than released by the Deepwater Horizon in the Gulf of Mexico.

And for the record, that 2005 study found that Canadian waters are home to as many as 2,100 wrecks holding up to 2.6 billion gallons of oil. The Zalinski was a promising start.

But Wait? There’s More! (As the TV hucksters say)

Text by Phil Nuytten

The 2013 removal operation from the Zalinski was far from a simple, straightforward diving project. The physical act of heating and pumping the oil out was a relative no-brainer, but the politics involved were something else again. The successful bidder for the 2013 tender put out by the department of Public Works and led by the Canadian Coast Guard was the Dutch company Mammoet Salvage. They hired a non-Canadian diving contractor to do the diving work.

British Columbia Divers Union Local 2404 protested against the use of non-Canadian divers who were allowed entry without work permits. The Canadian Association of Diving Contractors sent the following to the various participating Canadian government departments:

“It has come to our attention that Mammoet Salvage Inc. has engaged the services of Global Diving, a non-Canadian Company, to provide divers on a salvage project on the coast of British Columbia. This project will require the use of at least a dozen divers and their support staff who would be working under the direction of Mammoet. To the best of our knowledge, there are no Canadian divers on the project.

“We are at a loss to understand how a foreign company can have free reign to work in Canada / B.C. when there are many qualified Canadian divers available to perform the work. When any Canadian contractors have had to bring in specialized remotely-operated vehicle technicians, we have had to apply for permits and were granted those ONLY when it could be proved that no Canadians were available. Qualified and competent Canadian divers are available for this work.

“At the very least, the foreign diving contractor should be required to hire Canadian divers for this project, as we would have to do the same if we were working in the U.S or other foreign areas.

“On behalf of the Canadian Association of Diving Contractors, we request that this matter be looked into immediately to insure that available qualified Canadian diving personnel have the opportunity to work in their own country. They are available. Time is of the essence as the work is now being mobilized in Vancouver. We only recently learned at the last minute of the lack of Canadian content re: diving personnel. This is totally unacceptable.”

The Canadian Coast Guard responded thus: “The primary contractor has the ability to select other subcontractors as necessary to complete their work. In this case, Mammoet subcontracted Global Dive and Salvage from Seattle, Washington, to provide dive services to complete the operation. The selection of this subcontractor was made independently of PWGSC and the Canadian Coast Guard.

“Under section 186 (t) of the Canadian Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations, a foreign national may work temporarily in Canada without a work permit as a provider of emergency services. Both Mammoet and Global Diving Salvage were permitted to work in Canada under this provision due to the urgent nature of the services provided to complete the project.”

Let’s see…the ship sank in 1946 and began leaking oil immediately, according to First Nations Elders in the area. The nearly 70 years that have elapsed don’t really fit the description of ‘urgent nature’ – unless, of course, you’re measuring in geologic time. Interestingly, the 2013 tender for oil removal from the Zalinski was not the first such tender. In 2007, a tender was put out for ‘The Removal of Oil from the Sunken Vessel Brigadier General Zalinski’. The tender was issued by the Department of Public Works and Government Services Canada. That document states that, “the Zalinski is estimated to contain approximately 700 tonnes of bunker oil.” There were at least two qualified contractors who responded, but no contract was awarded and no reason was given for the non-award.

The results of a previous Coast Guard-ordered inspection described the leakage as “minimal” with an estimate of “about two tablespoons per day”. This jibes with the suggestion in Bob Osborne’s article that it “came down to a simple cost benefit analysis – she wasn’t causing much of a mess!”

Wow! If you do the math on 700 tonnes of Bunker C at two tablespoons per day… two tablespoons is about 30 millilitres, 700 tonnes is about 180,000 gallons, a gallon is 3,785ml. By 2013, the Zalinski had been down for 67 years, leaking up to 5.7 gallons a year, for a total of 388 gallons. Let’s see…180,000 gallons minus 388 gallons still leaves 179,612 gallons of Bunker C.

The 2013 Zalinski oil salvors estimated that they had removed “about 43 tons” of oil, which would be equal to about 11,000 gallons. If we’ve done our sums correctly, there would be 168,000 gallons still left in the Zalinski, which of course there is not. This means that either there wasn’t 700 tonnes to start, or the leakage rate was far higher than initially reported, or the leakage rate accelerated greatly over the years, or (most likely) all of the above.

A wreck loaded with oil and unexploded ordinance lay in a commercial shipping channel for nearly 70 years. The First Nations Peoples’ requests for removal or remediation were largely ignored. As the sidebar to this story notes, Canada does not have a mechanism in place to inventory the shipwrecks in this country for their environmental disaster potential – and it should have.

Ongoing Observation for Oil leaks

by Matthew Bossons

The Canadian Coast Guard’s (CCG) successful recovery operation on the General Zalinski late last year, removed 43 tonnes of bunker oil from the upside down ship, which sank en route from Seattle to Alaska with an estimated 700 tonnes of the toxic fuel in her holds.

“The consensus is that there was the initial release,” CCG Environmental Response Supervisor Daniel Reid told divers at the annual shipwreck conference of the Underwater Archaeological Society of B.C. in Victoria March 8. “It was understood going in there would be some residual,” Reid said, explaining that elders from the Gitga’at Nation who were kids when the ship sank, helped Coast Guard authorities understand how much oil spilled when the ship sank in September of 1946.

There’s been oil leakage over the years as well so that on completion of the salvage operation, 43,000 litres (43 tonnes) of intermediate fuel oil was recovered along with another 338,000 litres of oily water, later barged to Vancouver for reprocessing by a waste management company.

Salvors were faced with a problem at the outset when they discovered the oil had migrated from the fuel tanks they planned to drain. Divers had to drill holes at high points along the upturned hull that’s in about 100 feet (30m).

Reid said the salvage operation was conducted over 70 days and involved more than 100 salvage and spill response personnel at a total cost of over $20 million. Concern over a salvage-related spill required deployment of containment booms on location and there was “easily 1,000 tonnes of oil recovery capacity on site,” he said.

Aware that long-term observation will be required to ensure protection of Grenville Channel, Reid told the gathering that the Coast Guard has “An ongoing commitment to the people in communities there.”