Sweden’s Mine-Bender

A couple of hours northwest of Stockholm, Sweden offers up a dive site extraordinary for its location and blend of natural and manmade features. Known as the Tuna-Hästberg mine, it’s a vast web of water-filled passages tens of kilometres long, radiating in all directions far beneath the earth’s surface. Visibility in this deep, still water is beyond measure, a diver’s vision limited only by the beam of his or her light.

And there’s a lot to see. The mine is loaded with artefacts. Many structures have been located: buildings still stand, bridges remain intact, stairways climb, fences and their gates enclose.

Two ore wagons have been discovered, one still rolls on its tracks. And all preserved in the low oxygen water, their appearance changed little from the day the mine closed.

You can see tools lying about near construction sites in the complex of mine passages. Old lighting arrays still stand at the ready. You can swim into 50-year old electrical power stations.

Inside light bulbs remain in their sockets. And each one of these buildings is clearly identified with an enamel sign that pinpoints your location in the maze. In a distant locale there is a superbly preserved pump station from the 19th Century, the only one of its kind still known to exist.

Mine diving here is to cave diving what an artificial reef dive would be to the exploration of a natural reef. You encounter countless artefacts and signs of human activity, and in this case some of them are hundreds of years old, making each dive an exciting journey into past eras when the mine was integral to life in the community.

Today, more than four kilometres of permanent cave lines allow much exploration – though far more remains unexplored. The network of lines and permanent markings has been carefully documented and digitally recorded, allowing for future expansion and mapping. Currently, diving in the mine ranges from shallow water experience in the cavern zone to deep exploration with scooters and staged decompression. Maximum depth according to blueprints is about 1,300 feet (400m)!

15th Century Beginnings

First records of mining in Tuna-Hästberg date back to the early 15th Century; small scale excavations by the landowners. The resource here is a manganese-rich iron ore. Full-scale operations began in the 19th Century, reaching maximum capacity during the 20th Century by which time it had spread out over an area of more than 115 acres (47 hectares).

Closed in 1968, ground water in the abandoned shafts began to rise as soon as the constantly running bilge pumps were shut down. Most of the mine is water-filled, the surface currently 279 feet (85m) below ground level – the last dry level is at 262 feet (80m). The veins of ore are angled at 30° to 45°. These sloping passages level off deeper down where maximum water depth is in excess of 1,300 feet (400m), inaccessible to divers at present but no one’s complaining with more than six miles (10km) of water-filled passages open to any certified cave and nitrox diver.

A Taste For More

Nicklas Myrin and Daniel Karlsson from Baggbodykarna began a ‘dry’ exploration of the Tuna-Hästberg mine in 1998. When they encountered water down at the third level they immediately decided to take their hunt underwater. But it took over three years before their plan was realized. In early 2001 a test dive was planned and executed. No infrastructure existed to transport equipment down through the mine’s labyrinth of passages to the water. So, two lightweight diving rigs were lowered on ropes and the first dive was conducted in one of the big excavated ‘rooms’ in the cavern zone. That success gave them a taste for more. The visibility was amazing, but that wasn’t all. The first thing they encountered was a 20-foot (6m) high wooden bridge originating from a time when the ore was transported in wagons to the elevators and then to the surface. The old wooden bridge was perfectly preserved in the chill water and for them it was like the gateway into a lost world.

Unforgiving Environment

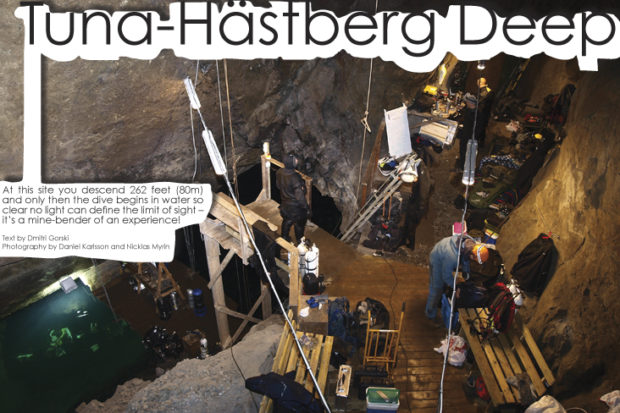

They realized significant resources would be needed to access this subterranean world. The mine environment is hostile… unforgiving. To dive you had to descend to the last dry level at 262 feet (80m). Making the descent with climbing gear and a helmet was fun and challenging, but in those early days pulling it off while carrying a full kit of cave diving gear at the same time seemed an impossible task. The first dives demanded hours of work from a support team that carried everything down. Air temperature in the mine is 34°F to 36°F (1°-2 ºC), and it is completely dark. Divers had to suit up by flashlight and their limited gas supplies, coupled with the very cold water, limited dives to a maximum of 20 minutes. All things considered, the site allowed just one dive a day.

Faced with these challenges, everyone worked to effect solutions for easier and safer diving. The main shaft, through which miners once descended, was still supported by huge beams and even old rails remained in place. A simple stairway was built, secured to the support beams, eliminating the need for ropes. The rails were a great help, too. Originally used to transport an ore wagon, they were refurbished to carry 800-pound (400kg) containers of dive gear to the dive staging level with the help of an electrical winch. Between 2005 and 2007 the mine underwent big changes. A transformer station was bought and then with electrical hook-up, permanent lights were installed in the mine. The diving base camp was moved closer to the water with the addition of a floating dive platform and heated room. The improved facilities included a place to charge lights and cook food.

Safety was a priority. A communication system was installed to relay cell phone calls from underground to the surface. The dive platform and ladder and electrical winching capability can facilitate expedient movement of an accident victim to the surface while the cell phone link permits immediate calls for ambulance assistance. These safety and logistical improvements have made it possible to explore the mine more efficiently – with scooters and mixed gas. A habitat for several divers is being built 20 feet (6m) underwater, providing safer and more enjoyable decompression when its construction is completed.

Recent History

The history of this mine spans some six centuries and while evidence of activity from hundreds of years ago is fascinating, so are the signs of more modern times. Down one narrow side passage not far from the main junction of lines near the dive platform, you can see the Östra-Västra sign (pictured at left), in an area that’s popular with regular and visiting divers. The sign is attached to a steel fence that surrounds the main shaft. Just beyond this point is an old control room filled with mechanisms and dials, likely used to operate and monitor the shaft elevators. In the centre of this room is a hole leading down to a service tunnel; an area that’s fun to explore. This facility bears witness to a more modern mine operation in which compressed air machines performed work once accomplished by manual labour. Under the roof of this structure you can see rows of light bulbs that once lit up the area during the mine’s last decades.

One of the coolest things in the mine is the variety of ladders and stairs. They’re everywhere and the design and construction of each reveals when they were made and in service over the years. The oldest are just round poles bound together by rope. Later, iron nails and brackets replaced rope making the stairs more durable and functional. For hundreds of years stairs were the only way for the workers to reach the surface – elevators were used expressly to transport the iron ore.

Here’s an interesting detail I learned when I visited the dry Falun copper mine during a work conference. The guide there explained why torches used in the mines were made with a small stick protruding from their side. When two mine workers met on a ladder, one of them had to swing around to the back or underside so the other could continue on his way. Because both hands were busy negotiating the ladders the miners held their torches in their mouths, biting on the small stick. This explains why so many miners depicted in paintings are bald and some even with eyebrows singed off.

In the Tuna-Hästberg mine there are many stairways just 300 feet (100m) distant from the base camp. In one area, there are four or five sets of stairs to be explored in a single dive, the longest of these measuring some 50 to 65 feet (15-20m). One set leads down to an old door that’s now almost gone. But the stout doorframe remains. These were built to control ventilation and acted as emergency fire doors. Bridges are evident throughout the mine. Solidly built to carry the weight of miners and heavy equipment, they traverse uneven floors, cracks and crevices and even streams, signs of which have not disappeared in this water-filled world.

Time Warp

The air is cold, damp and oppressive. A galaxy of flickering torches fracture the darkness that envelopes hundreds of miners as they break precious ore from the rock walls of the cavernous mine. From deep underground the iron ore is transported to the surface and refined into the metal consumed by the Swedish war machine. Bounty from Tuna-Hästberg together with natural resources extracted from Falun, Sala and other mine sites, feed Swedish imperial expansion over vast regions of Europe. Centuries ago, these mines were vital to Sweden, employing tens of thousands of people and generating much of the country’s wealth.

In one section of the iron ore mine the shift is changing. Miners who have spent weeks toiling in the dark are anxious to depart for their well-earned break. They gather at a timbered house from which they proceed to the main shaft where stairs lead to the world above and their waiting families. Preparing to leave, a miner’s hammer falls from his toolbox, landing with a dull thud in a pile of rubbish. Almost 200 years later, I float weightless over the same spot, near the disintegrating timbered house. I look down and see the hammer handle protruding from a pile of wood logs. Just then my dive buddy Nicklas Myrin beckons with his light, pointing to a spot where I can see a pair of toolboxes that appear left behind just yesterday. I move closer. In the boxes I see rusty metal bars that were used to anchor the mine’s roof supporting beams. I play mind games, imagining a scene played out hundreds of years ago at this exact spot where the toolboxes reveal themselves. I glance at the wider space in which we’re diving, now brightly lit by my powerful HID-light and I imagine the space filled with weary, grim-faced miners hard at their back-breaking work in the smoky yellow torch light.

I`d heard my friends Nicklas and Daniel talk about this particular hammer and the tool boxes, but from their directions I’d not been able find them. So, on the dive I just described Nicklas was my guide… into Sweden’s past, when she was a superpower. Many dives in Tuna-Hästberg are like that, a journey into a history preserved in the countless details and artefacts of a long dead time brought back to life.

This dive ended with a circuitous return to a line junction we’d come to just five minutes into the dive. From there we could see the powerful blue-coloured light filtering down from the stationary HID-array over the topside base camp. Momentarily, the light went out, blocked by a pillar we’d swum behind, and then it was there again, closer and brighter. We finned forward entering the enormous cavern zone to a spot directly under the floating platform where all our dives begin. Even at a depth of 100 feet (30m) we could see the underside of the platform clearly and silhouettes of a dive team just beginning their descent. Ascending, we reached the metal bar at 20 feet (6m) where we’d left our 02 decompression bottles. Because there is little room for error diving here, all dives are conducted with a wide safety margin; I always finish with a couple of minutes on oxygen, even on no-decompression dives.

After each dive, we leave our dive gear on the floating platform, climb about 15 feet (5m) up the dive ladder to a heated room furnished with benches and a table and where we can cook food and refuel. In the Tuna-Hästberg deep life is rigorous. Days are filled with physical activity. The heated room is a place to relax, share our dive experiences and discuss explorations to come. And in this subterranean world of ours there is always something to build or repair, so diving days are often followed by evenings spent working. Which may prompt you to ask what the future holds for this unusual dive site deep below the Swedish landscape? The plan is to make the mine more hospitable so that more and more people can visit and see that when it comes to overhead diving, Sweden has something truly special of a calibre equal to sites found in countries such as France, Mexico and Florida.