The (not so) Silent World

Since fall 2018, NOAA and the US Navy have been working with a number of scientific partners to study sound within seven national marine sanctuaries

Words by Rachel Plunkett

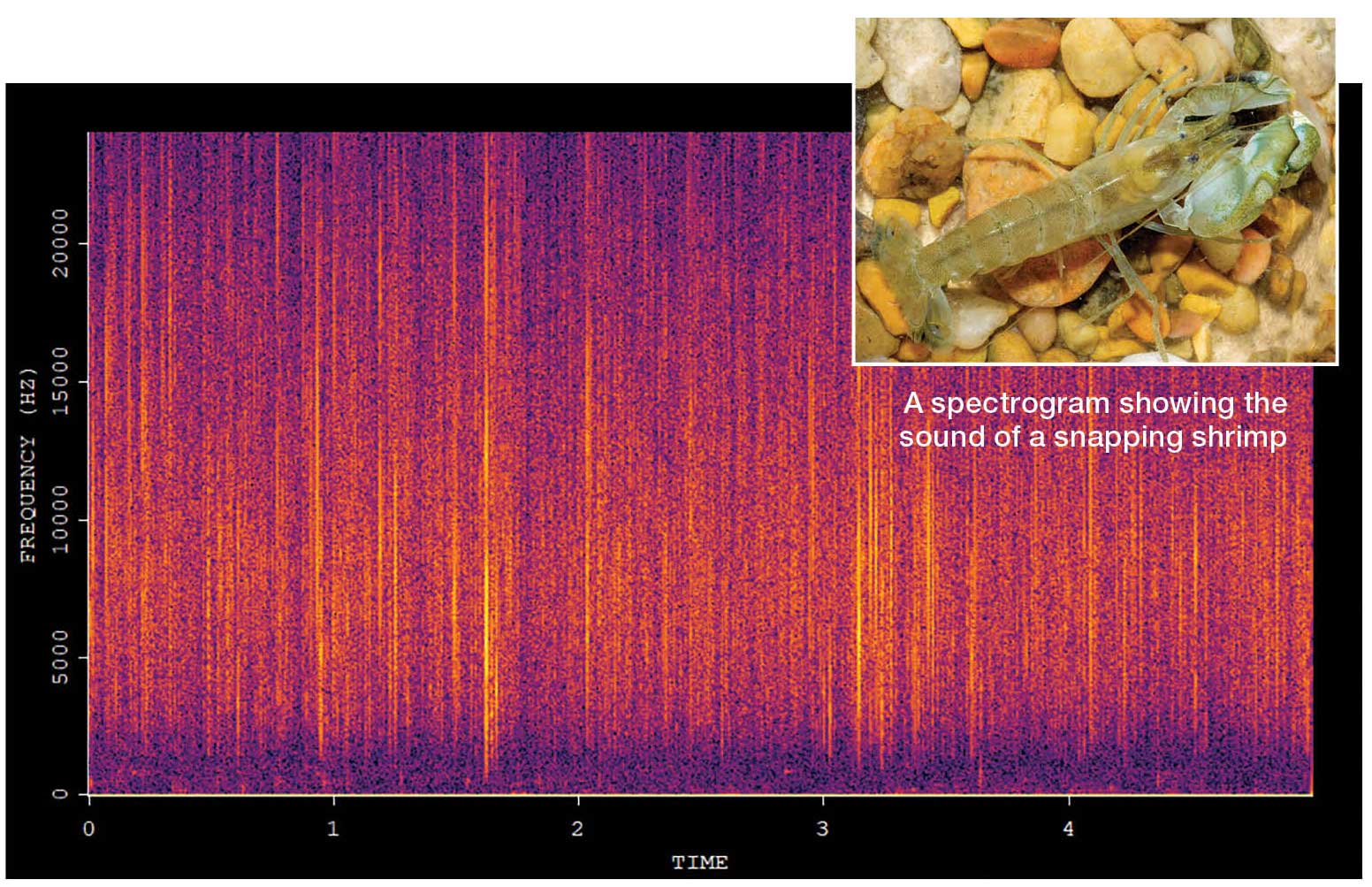

Have you ever travelled to a new city and noticed how different it sounds from home? Perhaps instead of hearing the sound of sprinklers turning on and birds chirping at 6 a.m., you notice the sound of honking car horns and rumbling subway cars. Different locations within the ocean have their own sound profiles, too. Depending on where you like to dive, you have probably heard the signature sounds of certain critters—perhaps the crunching sounds of parrotfish scraping algae off the coral, or the popping and crackling sounds made by snapping shrimp.

Sound is one of many ways that marine animals experience and navigate their environments, and it can provide useful information to researchers looking to characterize the diversity and health of marine ecosystems. We can find answers to questions like: Where are each of these sounds coming from? How do the sounds in a certain location change over time? How do the sounds heard in one location compare to another? How might human activities affect the sound environment?

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the U.S. Navy are working to better understand underwater sound within the National Marine Sanctuary System. Since fall 2018, the agencies have been working with a number of scientific partners to study sound within seven national marine sanctuaries and one marine national monument, in waters off Hawaii and the U.S. East and West Coasts. Standardized measurements are being used to identify sounds produced by marine animals, physical processes (such as wind and waves), and human activities. The data that results is being used to make comparisons across 30 nationally distributed locations.

Information from the SanctSound project will be available for the public to download and explore starting in 2022 via a ‘sound portal’. In the meantime, NOAA has published several articles about this work on the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries’ website.

Sound technology

Scientists need to be able to rely on standardized methods in order to characterize sound conditions accurately and compare them over time. Both stationary and mobile listening technologies are being used across sites. At each of the locations, sound is being recorded using a hydrophone (an underwater microphone) placed near the seafloor. Periodically, the instruments are retrieved to download the recordings and refresh the batteries. At shallower locations like those in Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary off the coast of Georgia, this equipment is placed and retrieved by scuba divers. At deeper locations such as those in Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, gear is deployed over the side of the sanctuary’s research vessels and allowed to sink to the seafloor using an anchored mooring line.

Gliders, a type of autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV), are also being equipped with hydrophones and deployed at some locations to follow a series of pre-programmed GPS waypoints, often in a lawnmower-like pattern. The glider uses gravity to descend in the water column and buoyancy to ascend, which makes it move in an up and down sawtooth-like pattern. When the glider periodically surfaces, it sends a signal to a satellite that records its GPS location and allows data to be transferred back to the lab.

Combining these technologies across multiple sites allows for streamlined and continuous datasets, even during challenging times such as the COVID-19 global pandemic. The technologies employed to collect this data are low-cost, non-invasive, and allow for round-the-clock research without ever laying eyes on the sound subject! “Listening can be as, or even more, effective than seeing. Listening has become a way for the sanctuary and its partners to monitor what is going on offshore during this time of social distancing,” said Dr. Leila Hatch, the sanctuary’s marine ecologist and co-lead for SanctSound.

What are we learning?

The ocean holds many mysteries and we have only touched the surface of what we can learn by listening underwater. For example, we can learn about the behaviours of fish, such as when certain fish are spawning; the migratory and breeding patterns of whales; and the impact of vessels and other human activities on animal behaviours.

SanctSound collects a large amount of information, and by the time the project wraps up in spring 2022, the instruments will have collected close to 300 terabytes of data. For context, approximately 500 hours of film can fit in one terabyte!

So what does all of this data mean and what will scientists do with it?

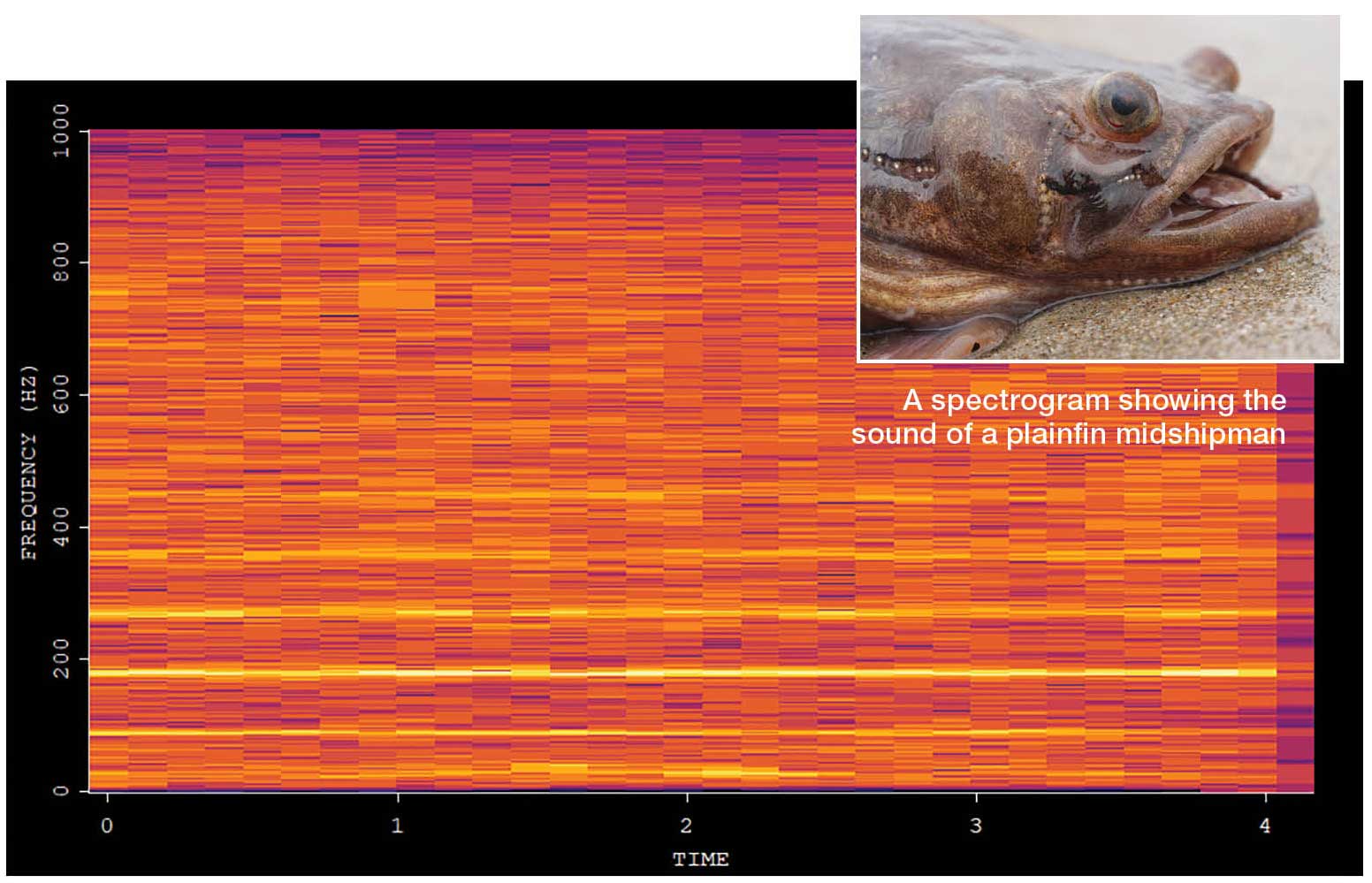

Hydrophones in Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary are being used to eavesdrop on fishy conversations. After listening in on the tonal calls of the plainfin midshipman for a few years, researchers have found that when a new sound enters their environment, the midshipmen go silent. This begs the question, how sensitive are these fish to human-made noise interference, such as the sound of ships?

In Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, researchers are using information from the soundscape to better understand fish abundance, diversity, and habitat type. Several sounds have also been recorded in the Florida Keys that belong to ‘mystery fish’, and researchers hope to continue studying these recordings to identify which fish species might be producing these sounds.

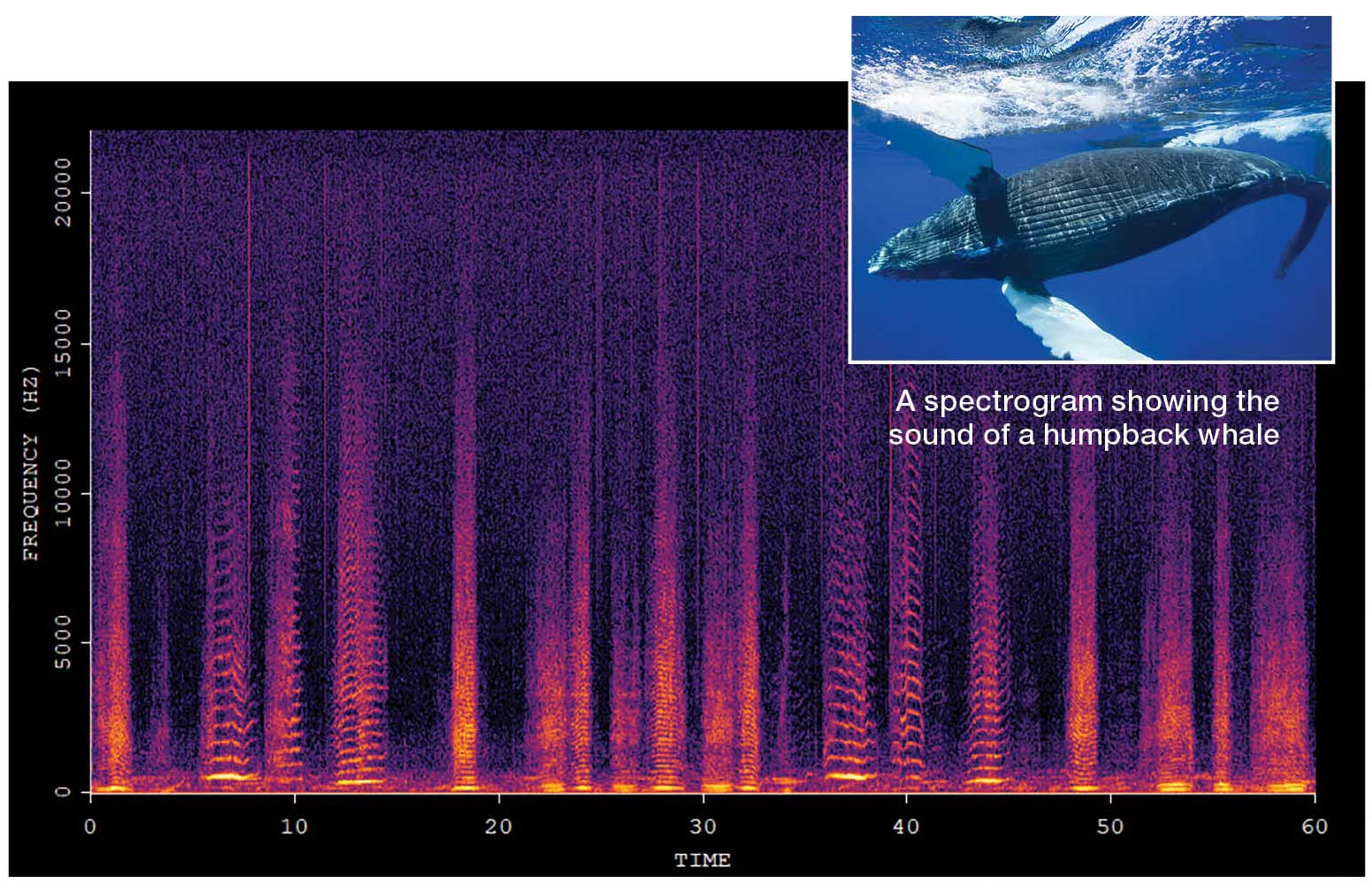

At Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, which encompasses more than 583,000 sq miles (1,510,000 km2) of waters in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, stationary recorders and wave gliders are being used to monitor the occurrence of humpback whale song and vessel activity. This data is helping researchers better understand where in the monument humpbacks occur, and which areas are likely being used for breeding. This information could lend to informing better policies for protecting humpbacks throughout the area in the future—especially in areas trafficked by large vessels.

Valuable data

Researchers have also found that only a few types of sounds are present at all of the project’s recording locations—the underwater sounds made by vessels both big and small. In Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, a network of hydrophones revealed a clear contribution by visiting cruise ships to the local soundscape of Monterey Bay. This is valuable information, considering over 36 different kinds of whales, dolphins, and otters are residents of or visit Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary annually—all of which rely on sound.

On the other hand, some sounds were present at a handful of specific locations, including sounds made by snapping shrimp, which are heard in Gray’s Reef, Florida Keys, Channel Islands, and Hawaiian Islands Humpback national marine sanctuaries.

As land-dwellers, we are used to sound traveling pretty slowly in air. But sound speeds up considerably underwater, increasing its efficiency in carrying messages for marine animals. Although light might still be faster, sound can travel much farther than light can underwater. This means that while scuba diving, you can likely hear things off in the distance that you might not be able to see. Animals that spend their lives underwater have adapted to make use of these properties, especially at very low frequencies below what humans can hear, listening to sounds that can travel for hundreds of thousands of kilometres.

Combining data about the marine environment using both sound (listening) and light (visual observations), allows us to get a much more complete picture of the biodiversity and health of sites, and observe changes over time. Using sound data collected by stationary and mobile hydrophones helps us learn things about the marine environment that we simply couldn’t see with our eyes, or detect with our ears while scuba diving. The fact that these instruments can stay underwater and keep recording much longer than a person could stay down to collect data, adds to the value of this approach to studying marine environments.

Coast to coast

Monitoring is taking place in Stellwagen Bank, Gray’s Reef, and Florida Keys national marine sanctuaries (East Coast); Olympic Coast, Monterey Bay, and Channel Islands national marine sanctuaries (West Coast); and Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary and Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (Pacific Islands Region). Hear the results at: sanctuaries.noaa.gov

Leave a Comment